On September 9, 2014, the BMJ published an article by Sophie Billioti de Gage et al. The article is titled Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. The research was a study based on data from the Quebec health insurance program database.

Here are the authors’ conclusion:

“Benzodiazepine use is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The stronger association observed for long term exposures reinforces the suspicion of a possible direct association, even if benzodiazepine use might also be an early marker of a condition associated with an increased risk of dementia. Unwarranted long term use of these drugs should be considered as a public health concern.”

Here’s how the study was conducted:

Individuals were selected as “cases” for the study if they met the following criteria:

1. “a first diagnosis (index date) of Alzheimer’s disease…recorded during the study period without any record of another type of dementia at the index date or before”

2. “absence of any anti-dementia treatment before index”

3. “at least six years of follow-up before the index date”

Each person with Alzheimer’s was matched on gender, age group, and duration of follow-up (6, 7, 8, 9, or 10 years) at the index date with four controls. Both cases and controls were randomly selected from people over age 66 living in the community in 2000-2009.

Data on benzodiazepine use was collected for each case and four controls for the period 5-10 years before the index date. The following data was collected:

1. any use of a benzodiazepine during the stated time frame

2. cumulative dose

3. whether the benzodiazepine used was long (> 20 hours) or short (< 20 hours) elimination half-life.

The specific benzodiazepines identified in the study were:

Long-acting: bromazepam; chlordiazepoxide; clobazam; diazepam; flurazepam; nitrazepam; clonazepam.

Short acting: alprazolam; lorazepam; oxazepam; midazolam; temazepam; triazolam.

Here are the results:

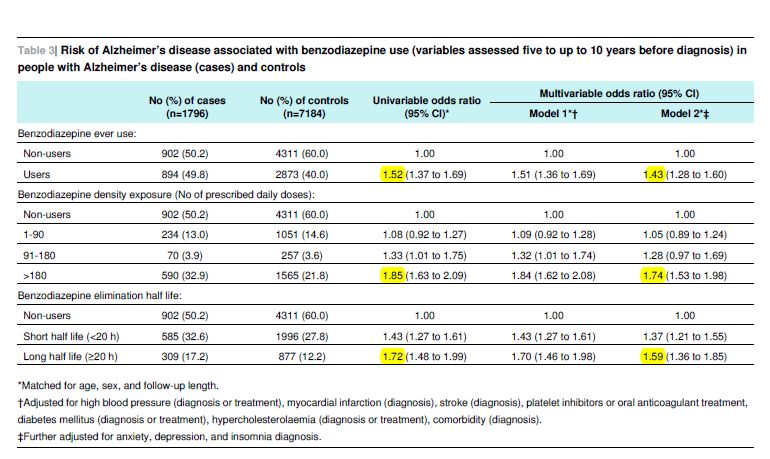

In summary: Use of benzos was significantly associated with an increased risk of AZD. The odds ratios are: 1.52 for any use; 1.85 for long-term use (6 months or more); and 1.72 for use of benzos with a long half-life. The corresponding odds ratios, after adjustment for potential confounders including anxiety, depression, and insomnia, were 1.43, 1.74, and 1.59 respectively. The 95% confidence limits for each of these ratios are shown in the table.

Here are some quotes from the discussion section of the paper:

“Risk increased with density of exposure and when long acting benzodiazepines were used. Further adjustment on symptoms thought to be potential prodromes for dementia—such as depression, anxiety, or sleep disorders—did not meaningfully alter the results.”

“Our findings are congruent with those of five previous studies…”

Limitations: This was a case-control study; not a randomized, controlled trial. Therefore it is not possible to say with absolute certainty that the benzodiazepine use caused the excess incidence of AZD. It could be argued, for instance, that the benzos were being prescribed to treat early (prodromal) signs of AZD. This would be an instance of what’s called reverse causation bias. However, the authors took particular pains to inoculate the study from this bias:

1. They did not count as “cases” people who received benzos in the five years prior to the AZD diagnosis date. So if the finding is an instance of reverse causation, it has to be acknowledged that the AZD had an extremely slow and, incidentally, unrecognized onset.

2. They measured cumulative dose and found a direct association between the magnitude of the dose and the risk of contracting AZD.

3. They noted whether the benzos used were long or short acting and found the association stronger in the former. This is essentially another cumulative dose measure. A person taking a 20-hour benzo daily is always effectively “dosed”, whereas a person taking a 2 hour compound daily will have significant breaks from the drug every day.

4. They calculated the odds ratios after adjusting for the presence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. These are the kinds of problems for which benzos are often prescribed, and could conceivably also indicate the early stages of AZD. The fact that the association was still strong after adjusting for these factors makes the possibility of reverse causation bias even less likely.

Some more quotes from the study:

“Dementia is currently the main cause of dependency in older people and a major public health concern affecting about 36 million people worldwide. Because of population growth and demographic ageing, this number is expected to double every 20 years and to reach 115 million in 2050.”

“Prevalence of use [of benzodiazepines] among elderly patients is consistently high in developed countries and ranges from 7% to 43%.”

“Although the long term effectiveness of benzodiazepines remains unproved for insomnia…and questionable for anxiety…their use is predominantly chronic in older people.”

“Our study reinforces the suspicion of an increased risk of Alzheimer type dementia among benzodiazepine users, particularly long term users, and provides arguments for carefully evaluating the indications for use of this drug class. Our findings are of major importance for public health, especially considering the prevalence and chronicity of benzodiazepine use in older people and the high and increasing incidence of dementia in developed countries.” [Emphasis added]

PSYCHIATRY’S REACTION TO THE STUDY

In general there has been little reaction from psychiatry to the study. I was unable to find any comment from the APA or from the Royal College of Psychiatrists. I have found a small number of comments from individual psychiatrists.

Guy Goodwin, MD, is a professor of psychiatry at Oxford University in the UK. He is also president of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. In a BBC article dated September 9, he is quoted as saying that the findings:

“…could mean that the drugs cause the disease, but is more likely to mean that the drugs are being given to people who are already ill.” [Emphasis added]

There’s no indication in the BBC article that Dr. Goodwin cited any evidence for this assertion, or that he made any reference to the steps that the authors took to counteract precisely this kind of reverse causation bias.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I also found a comment from Abbot Granoff, MD, a psychiatrist practicing in Norfolk, Virginia. His comment was in response to a CBS article. Here are some quotes from his comment.

“I am a Board Certified Psychiatrist…”

“I have been successfully prescribing benzodiazepines for the past 35 plus years in my private practice.”

“…anxiety, depression or insomnia might be early symptoms of dementia whatever the cause. Prescribing a benzodiazepine to treat these symptoms does not cause the illness.”

“Because of age, liver function (which breaks down medications) or brain function might already be compromised and cause the side effects of sedation and memory loss to become more severe. These side effects are dose related. Reducing the dose eliminates the side effects. They are not permanent.”

Again, there is no evidence, and no serious acknowledgement of, the issues – just the comforting (?) assertion that “prescribing a benzodiazepine to treat these symptoms does not cause the illness.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By way of contrast, I found an interesting comment in the BMJ’s rapid response section. The comment is from Eric Lenze, MD, geriatric psychiatrist, et al, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. Here are some quotes:

“A mass of evidence suggests that the benefits of benzodiazepines in older adults rarely, if ever outweigh their risks.”

“Benzodiazepine risks, whether short-term or chronic, include cognitive impairment, delirium, respiratory insufficiency, falls, fall-related injuries such as hip fractures, motor vehicle crashes, and death.”

“The main risk factor for chronic benzodiazepine use is any previous use, so an intended short-duration prescription of these habit-forming medication is likely to lead to their long-term use.” [Emphasis added]

“Benzodiazepines’ benefits for anxiety disorders are questionable, especially as they are commonly used in clinical practice. First, the dose of benzodiazepines necessary to provide a clinical response is far higher than that needed to cause harms in older adults – for example, 6-10mg daily of alprazolam is needed to bring about remission from panic disorder, and 30-60mg daily of oxazepam was needed for response in (to our knowledge) the only controlled study of benzodiazepines for anxiety disorder in older adults. Second, there is growing evidence in anxiety disorders that benzodiazepine use reduces the efficacy of exposure-based cognitive behavior therapy, probably by interfering with learning and memory and preventing habituation to the anxiety. Hence, benzodiazepine use may actually perpetuate (rather than treat) many anxiety disorders by preventing naturalistic recovery from them.”

“The evidence for benefits of benzodiazepines in insomnia is equally poor. In a meta-analysis, benzodiazepine use resulted in a mean nightly improvement of 25.2 minutes sleep. The number needed to treat for improvement of insomnia was 13, while the number needed to harm was 6.”

“For occasional insomnia or transient anxiety, watchful waiting or other low-intensity intervention are superior to initiating a dangerous and habit-forming medication.”

“To conclude, Billioti De Gage and colleagues provide more evidence still that deleterious consequences of benzodiazepines in older adults are a large and growing public health problem, given their high rates of use in this age group. It is time for their use to be limited, for example to palliative and hospice care or specific treatment-refractory cases, and as a start we recommend the following:

1. Clinicians prescribing these medications to older adults should warn them that their use is not considered best practice.

2. These medications should come with a warning (like that found on cigarette packages) such as “If you are older than 60, use of this medication will increase your risk of cognitive impairment, falls, hip fractures, and death.”

3. Educate health care providers regarding (a) risks of short-term and long-term benzodiazepine use and (b) safe alternatives for the management of anxiety and insomnia.”

“Competing interests: none to report”

There are 20 references attached to this comment, so it’s a good source document for anyone wanting to research the facts about these dangerous drugs.

A CONSUMER’S REACTION TO THE STUDY

Here’s another comment from the BMJ’s rapid response thread:

“I have been prescribed generic Xanax for about 9 years, at dosage between 5mg and 1mg/day. I am 45. This study is clearly alarming, and honestly terrifying.

How are my odds of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s figured? I can only imagine that I am in increased likelihood of about 8,000%. Based on the 3-6 month likelihood rates.

My doctor says, ‘Just keep taking it. Benefits outweigh the risks.’ Clearly, they do not! I have not slept nor eaten well since I read the study. Can anyone explain the likelihood ratios that are mentioned? And is there evidence of the disease showing up in younger people after taking benzos for years?

Any help, and perspective at all would be so very much appreciated!”

DISCUSSION

So, if a person in mid-life is feeling anxious, or depressed, or can’t sleep? No problem. No need to figure out the source of these concerns. No need to work towards solutions in the old time-honored way of our ancestors. Today, psychiatrists have pills. Pop a benzo! And by the way, you’ll have a 40% increased risk of AZD in your late sixties. And if that makes you anxious, don’t worry; psychiatrists have neuroleptics and electric shock “treatment” to “manage” dementia.

All psychiatric drugs exert their effect by distorting normal brain function. They all cause damage, especially when ingested for prolonged periods. The present study simply confirms and quantifies this phenomenon. Psychiatry’s usual response to this is to assert that the benefits of their “treatments” outweigh the risks. But by what Faustian calculus can one compare the short-term chemical dissipation of anxiety with the medium-term risk of AZD?

There is truly no human problem that psychiatry can’t make ten times worse. The notion that all the great trials of life, and particularly aging, can be resolved by dispensing addictive drugs is fundamentally spurious, disempowering, and insulting. The notion that such activity would masquerade as a legitimate medical specialty is a travesty, to which our descendents will one day hold psychiatry accountable.

Anxiety and depression are not illnesses. They are normal human responses to various kinds of problems that are an integral part of what it means to be human. The only effective way to cope with anxiety or depression is to confront, and resolve, the underlying causes, either by one’s own efforts, or with the help of others. Taking psychiatric drugs to “treat” these feelings is no different than “drowning one’s sorrows” in a bottle of whiskey. Both products are highly addictive, and the long-term results are comparable.

DETOXING FROM BENZOS

Detoxing from benzos, even after relatively short-term use, can be extremely difficult and fraught with problems. These drugs should never be stopped abruptly. For information on withdrawal from benzos, see Monica Cassani’s site Beyond Meds.