On September 9, 2014, the BMJ published an article by Sophie Billioti de Gage et al. The article was titled Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study, and concluded:

“Benzodiazepine use is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The stronger association observed for long term exposures reinforces the suspicion of a possible direct association, even if benzodiazepine use might also be an early marker of a condition associated with an increased risk of dementia. Unwarranted long term use of these drugs should be considered as a public health concern.” [Emphasis added]

On October 17, I wrote a post on this topic. In that post I noted that I had not been able to find an APA comment on the BMJ article. In fact, on October 15, Psychiatric News, the APA’s online publication, had posted Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines May Be Linked to Alzheimer’s, by Vabren Watts, PhD. The article is pure damage control.

The problem for the APA is that the evidence implicating benzos as a causative factor in the development of Alzheimer’s disease is mounting. The APA can’t ignore this reality, but at the same time they can’t afford to alienate either pharma, or their own members who are prescribing these products. So they’re having to walk a tight line.

Here are some quotes from the Psychiatric News article, interspersed with my comments.

“Researchers caution physicians to take more care when prescribing benzodiazepines.”

Strictly speaking, this is accurate. Dr. de Gage et al did indeed write: “…treatments [with benzodiazepines] should be of short duration and not exceed three months.” But they also wrote:

“Our study reinforces the suspicion of an increased risk of Alzheimer type dementia among benzodiazepine users, particularly long term users, and provides arguments for carefully evaluating the indications for use of this drug class. Our findings are of major importance for public health, especially considering the prevalence and chronicity of benzodiazepine use in older people and the high and increasing incidence of dementia in developed countries. In such conditions, a risk increased by 43-51% in users would generate a huge number of excess cases, even in countries where the prevalence of use of these drugs is not high.” [Emphasis added]

“Carefully evaluating the indications for use” of a drug class, is light-years beyond taking “more care when prescribing.” The former denotes a complete re-appraisal of the status quo. The latter is little more than platitudinous encouragement.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“‘Prevalence of [benzodiazepines] use among elderly patients is consistently high in developed countries … [ranging] from 7 percent to 43 percent,’ noted the researchers.”

This is the first quote that Dr. Watts provides from the de Gage et al study, and although it provides an important demographic reality, it is not the main issue. This is a nice example of the spin tactic known as deflection, and watch how skillfully Dr. Watts uses it. His next sentence reads:

“International guidelines recommend short-term use of the drug, mainly because of withdrawal symptoms that make discontinuation problematic; however, the study noted, use of benzodiazepines is often long term in older people.”

The issue here is that benzodiazepines, for decades one of the mainstays of psychiatric prescribing, are almost certainly causing AZD in millions of victims world-wide. But Dr. Watts has adroitly shifted to a discussion of the over-use of those drugs and the potential for addiction when used long-term. Again, these are important issues, but they are not central to the de Gage findings. It is also worth noting that people can become thoroughly hooked on these products even with very short-term use, and that the overuse of these drugs was fuelled primarily by psychiatrists, who for years assured the public, and other medical practitioners, that these drugs were benign and non-addictive.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Having found a safe angle, Dr. Watts stays with it.

“‘Somewhere along the way, the message got lost, and patients were allowed to use benzodiazepines for months and years,’ said Mohit P. Chopra, M.D., a member of APA’s Council on Geriatric Psychiatry. Chopra, who was not involved with the study, told Psychiatric News that guidelines recommend that the anxiolytic and insomnia medicines are to be used on a daily basis for no longer than four to six weeks.”

This is a slick rewriting of history. In fact, the message didn’t get lost. The original message, as propagated by psychiatrists, was that benzos were safe and non-addictive. “Patients” weren’t just allowed to use benzos for months and years. They were actively encouraged to do so, and in many cases were told the standard psychiatric lie that these products would correct non-existent anomalies in their brains. The promotion of benzos by the psychiatry-pharma alliance is one of the great commercial success stories of this business.

And the APA continues to promote these drugs, albeit indirectly. In their online section on anxiety disorders, under the heading “For more information” they give links to Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA) and National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH). Here’s a quote from the ADAA site (under the heading Finding Help: Treatment):

“Benzodiazepines

This class of drugs is frequently used for short-term management of anxiety. Benzodiazepines (alprazolam, clonazepam, diazepam, and lorazepam) are highly effective in promoting relaxation and reducing muscular tension and other physical symptoms of anxiety. Long-term use may require increased doses to achieve the same effect, which may lead to problems related to tolerance and dependence.”

And here’s a quote from the NIMH link:

“High-potency benzodiazepines combat anxiety and have few side effects other than drowsiness.”

These quotes are in marked contrast to the statement of Eric Lenze, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist, et al:

“Benzodiazepine risks, whether short-term or chronic, include cognitive impairment, delirium, respiratory insufficiency, falls, fall-related injuries such as hip fractures, motor vehicle crashes, and death. Most patients are not warned of these risks before starting these medications. The main risk factor for chronic benzodiazepine use is any previous use, so an intended short-duration prescription of these habit-forming medication is likely to lead to their long-term use.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Eventually, of course, Dr. Watts has to provide some information from the BMJ study. He gives a very brief description of the research design and the results. He mentions the finding that benzodiazepine use six years earlier was associated with an increased risk for AZD, and that this association was maintained after adjustment for anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders.

And then another PR gem:

“The researchers concluded that benzodiazepines are ‘indisputably valuable tools for managing anxiety disorders and transient insomnia,’ but warned that treatment with these medications should be used within the time parameters set by international guidelines.”

The researchers did indeed write this, but it was a sideline to the main issue, and the quote did not come from their conclusions section, which I have quoted in full above. The primary conclusion is that the evidence for a direct causal link between benzo use and AZD is steadily mounting.

Dr. Watts’ primary concern throughout the article is to dispel any suggestion that benzos are inherently dangerous and damaging, and to promote the notion that they are only problematic when over-used. To this end, he now introduces the very eminent psychiatrist Davangere Devanand, MD, director of geriatric psychiatry at Columbia University.

“‘These findings emphasize the importance of restricting the use of benzodiazepines in the elderly population,’ said Devanand in an interview with Psychiatric News. ‘Benzodiazepines are known to be associated with an increased risk of worsening cognition … even in cognitively normal elderly subjects.’ Devanand said that in such situation, it would be best to taper and cease patients’ use of the benzodiazepine while reevaluating cognition functioning.”

And then, Dr. Devanand continues with a truly perfect piece of spin:

“‘If the cognitive decline is due to benzodiazepines, and the patient does not have an underlying dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease, the cognitive decline should reverse after stopping the treatment.'” [Emphasis added]

In other words, he is saying: Yes, benzos can cause some cognitive impairment, but it’s temporary, and will clear up if the pills are stopped.

And if it doesn’t clear up, then the individual must already have had AZD or some other dementia. The benzodiazepines couldn’t have caused permanent cognitive impairment. Dr. Devanand provides no evidence or references to support this contention, but he’s an eminent psychiatrist, so I suppose his assertion should be evidence enough. Besides, who ever heard of a psychiatric drug causing damage?

But then, wanting to have his cake and eat it too:

“Devanand stressed that in order to ensure that prescribers are not putting their patients at risk for the onset of neurocognitive disorders, ‘benzodiazepines should be prescribed sparingly and for short periods.'”

So benzos don’t cause permanent cognitive impairment, but to avoid putting patients at risk, they should be used “…sparingly and for short periods”!

And besides, there’s a beautiful little catch to the notion of prescribing benzos for short periods. When discontinuation is attempted, the client, as often as not, experiences withdrawals, and becomes agitated. And agitation, of course, calls for medication. And what medication is remarkably effective for suppressing agitation? Benzos! Isn’t psychiatry just wonderful. Not only can it damage people with its drugs, it can “treat” the damage with the very same drug – and do it all with a straight face!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

DISCUSSION

The gist of Dr. Watts’ article is:

- Benzos are generally safe if used for short periods (i.e. up to 3 months);

- If they are used for longer periods, they may cause some cognitive impairment, but it’s unlikely to be permanent

But there is no mention of what, at least in my view, is the most important point in the de Gage et al report:

“Our findings are congruent with those of five previous studies, two of which explored the modifying effect of the dose used. In four studies, the role of a putative protopathic bias could not be ruled out because an insufficient duration of follow-up; a lack of statistical power in subgroup analyses; and no consideration of the most relevant time window for exposure and ascertainment of confounders. The most recent study found a similar 50% increased risk within the 15 years after the start of benzodiazepine use (average length of follow-up 6.2 years). This excess risk was delayed and thus not indicative of a reverse causality bias. Another study found a positive association, though lacked significance because of its limited sample size.”

In other words, there is mounting evidence that benzodiazepines are causing AZD. I cannot imagine any genuine medical specialty ignoring or downplaying information of this sort. But psychiatry, with the perennial defensiveness of those with something to hide, promotes the idea that they are safe when used for short periods, knowing full well that a huge percentage of users become “hooked” after a week or two, and stay on the drugs indefinitely.

In the 80’s, I knew a psychiatrist who used to quip: “The difference between Xanax and true love is that Xanax is forever. You don’t take people off Xanax.” I wonder how many of his “patients” have Alzheimer’s disease today? And remember, Alzheimer’s is a truly devastating disease.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In addition, the notion that the drugs are safe if used for 3 months or less is questionable. There is no magic dividing line between three months and four months. If a drug causes damage when used for four months, then it is reasonable to infer that it causes damage when used for three months. The degree and scope of the damage for most people will probably be less, but it won’t be zero.

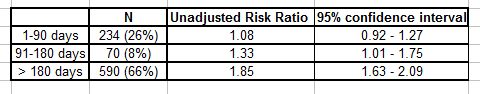

The relevant figures from the de Gage study are:

Relative Risk of AZD: Benzodiazepine Users vs. Non-Users

The point about the 1.08 risk ratio for the 1-90 days individuals is that, given the sample size, it is too close to 1 to say definitively that it represents a real increase in risk. There is a 95% probability that the risk for all 1-90 day users lies between 0.92 and 1.27. So it could be just a random fluctuation in the data.

But when all these risk ratios are considered together, the most obvious interpretation of the table is that the risk is trending upwards as the cumulative dosage increases. And bear in mind that the 1.08 ratio represents an average of people who have taken the pills for just a few days as well as people who took them for the full three months. For the latter, the risk will almost certainly be considerably higher than 1.08. The only thing we can say for sure about the 1-90 day users is that we can’t say anything for sure. There is nothing in the de Gage et al data to suggest that the drugs are safe for use up to three months, and in fact, strong grounds for thinking otherwise.

Designing a randomized controlled trial to check for a causal link poses enormous problems, not the least of which is that almost all participants will be able to tell if they’ve received a benzo or a placebo. In addition, an RCT has to be done prospectively. So we wouldn’t have the results for another 10 or 15 years! By all means this study should be undertaken, but meanwhile, shouldn’t we go with the best data that we’ve got?

The overall picture here is a steady accumulation of evidence that the drugs are causing AZD in some people, that the risk is dose-contingent, and that for people who have taken the drugs for 6 months or longer, the risk is approaching two-fold. It is also particularly noteworthy that of the 894 study participants who used benzos, 66% took them for 6 months or more.

Certainly, less use is better than more use, but promoting the message that use up to 3 months is safe strikes me as irresponsible. Given the numbers of people taking benzos and the number of people contracting AZD, risk ratios as low as 1.1 or even 1.05 represent an enormous additional burden of preventable disease. This is particularly relevant in that neither anxiety nor depression is an illness, and although popping a benzo may provide a temporary sense of relief, there are better ways to cope with these problems, that don’t entail any increased risk of AZD.

AND INCIDENTALLY

Vabren Watts’ specialty is cardiology research. He has a PhD in biomedical sciences from Meharry Medical College, and he completed his training in cardiology research at Johns Hopkins. He has worked as a Science Expert Ambassador and as a Health Science Leader and Spokesperson for the American Heart Association. He is the founder of The Science Journalist, where he provides freelance science/health reporting and technical writing services to various media outlets. Since 2013, he has worked for the APA as a Senior Staff Writer on Clinical and Research News for the APA.

On his bio summary, he describes himself as a:

“Biomedical researcher and health science communicator dedicated to making scientific findings and policies more comprehensible to medical experts, stakeholders, and lay audiences.”

Two things strike me as noteworthy: firstly that the APA has hired a professional writer (rather than a psychiatrist) to broadcast the de Gage result; and secondly, that the writer’s specialty is biomedical research. So much for psychiatry’s recent attempts to persuade us that they have always espoused a biopsychosocial approach.

Also, I am reminded of a paragraph in Jeffrey Lieberman’s final Psychiatric News article as APA President.

“Mindful of the continuing stigma associated with mental illness and psychiatric treatment, we retained an outside consultant agency (Porter Novelli) to review APA’s communications capabilities, needs, and opportunities. Based on its report, we are now moving forward with an initiative to enact a sophisticated and proactive communications plan that will be directed both internally to APA members and externally to the media, mental health stakeholder groups, and the general public.”

So, to counteract stigma (which, incidentally, is largely a product of psychiatry’s spurious medicalization of human problems), the APA, with the help of a prestigious PR firm, has set up “a sophisticated and proactive communications plan.” And presumably the hiring of Vabren Watts, and other talented young writers, is an integral part of this plan.

So here’s my question: If everything one is doing is honest, above-board, and clearly beneficial, why would one need “a sophisticated and proactive communications plan” to communicate with one’s own members, the media, and the general public?

And why does the APA need to re-package the eminently clear message of the de Gage et al report?