BACKGROUND

A couple of days ago (June 12) I posted Autism Prevalence Increasing. The article drew attention to a post by Kelly Brogan, MD, called See No Evil, Hear No Evil which had appeared on Mad in America on June 9. Dr. Brogan’s article had cited an alarming increase in the incidence of autism over the past few decades, and mentioned some possible causative factors.

I checked the figures against the DSM and CDC prevalence estimates and found they were broadly in line. I mentioned the possibility that diagnostic expansion, particularly as embracing milder presentations, might be a confounding factor, but that given the reported increase (1 in 5000 to 100 in 5000) over 38 years, I expressed the view that this was a bit of a stretch.

Subsequently on Twitter, John McGowan of CCCU Applied Psychol wrote:

“Wonder if huge autism increase in 40ish years based on subjective factors really a stretch? 1975 a foreign country. When I compare my kids’ experience at school to mine in the 70s. So, so much more emphasis on diagnosis now.”

This is an important question that I thought warranted some examination.

AUTISM AND DSM

From a purely logical point of view there are three possibilities. The incidence of autism is either: increasing; decreasing; or staying about the same. On the face of it this looks like an empirical question that could be readily answered by conducting a fairly straightforward retrospective survey.

However, we must first have an unambiguous definition of autism.

DSM defines its so-called “mental disorders” by listing a set of “diagnostic” criteria, and requiring that the individual score positive on a certain percentage of these items (e.g. 2 out of 4; 3 out of 5, etc.).

Here are the DSM-IV criteria for autistic disorder:

A. A total of six (or more) items from (1), (2), and (3), with at least two from (1), and one each from (2) and (3):

(1) qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

(a) marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors, such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction

(b) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

(c) a lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest)

(d) lack of social or emotional reciprocity

(2) qualitative impairments in communication, as manifested by at least one of the following:

(a) delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gesture or mime)

(b) in individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others

(c) stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language

(d) lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level

(3) restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities as manifested by at least one of the following:

(a) encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

(b) apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals

(c) stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting or complex whole-body movements)

(d) persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

B. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years: (1) social interaction, (2) language as used in social communication, or (3) symbolic or imaginative play.

C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Rett’s disorder or childhood disintegrative disorder.

There are two problems with this definition. Firstly, the individual items are vague. Consider item A (1)b: ” failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level.” The wording of this item presupposes that there exists a clear standard of peer relationships appropriate to the child’s developmental level.

(There is, incidentally, a purely logical problem with this item, in that peer relationships constitute an intrinsic element of developmental level. It’s a bit like a weather forecaster saying that it will rain today if there are showers. But let’s be gracious to Allen Frances and his DSM-IV colleagues, and assume that they meant to say “…developmental level in other areas,” or something similar.)

Of course there are such standards, but they’re not as clear cut or precise as the item cited above presumes; nor, I suggest, are they all that well known by people making the “diagnosis.” The extreme cases are fairly easy to identify, e.g. a child who sits in the corner by himself in a playroom and doesn’t interact at all with the other children. But what if he interacts once in a one-hour observation period? What about twice? And so on. Also, perhaps we should look at the quality of the interaction. If he gets up once in the hour and bashes another child on the head with a toy, would we rate this the same as approaching the other child and giving him the toy? Probably not.

Also, we have to ask: who’s doing the rating? There’s a good deal of research dating, if I remember right, back to the 60’s that suggests that if a teacher is told that a particular child is very bright, but just needs some extra encouragement, he/she will tend to rate that child as brighter than a teacher who is told that the child isn’t very bright. (Incidentally, this body of research is almost universally ignored in psychiatric “diagnosis.”)

But even if we ignore all these difficulties, there’s still the fact that the appropriateness of peer relationships, however accurately we might try to define it, is inevitably a continuous variable. It will never be a question of “yes” or “no,” but rather “how much.” And an additional complication: it will be “how much in such and such a situation, at what time of day, in whose company, etc., etc., etc….” The only way to dichotomize this kind of data is arbitrarily. But in fact DSM doesn’t even address these kinds of issues. Practitioners are forced to make a “yes” or “no” determination on each item and then count the items. Which brings us to an even more serious problem.

The first line of the APA’s definition reads: ” A total of six (or more) items from (1), (2), and (3), with at least two from (1), and one each from (2) and (3)” This is a common feature throughout the DSM, and represents a major weakness, in that it involves assigning the same “diagnosis” to people whose presentations may be quite different.

Take just two examples:

Child 1: meets only the following items from the DSM list:

1 (b) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

1 (d) lack of social or emotional reciprocity

2 (d) lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level

3 (a) encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

3 (b) apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals

3 (c) stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting or complex whole-body movements)

Child 2: meets only the following items:

1 (a) marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors, such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction

1 (b) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

1 (c) a lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest)

1 (d) lack of social or emotional reciprocity

2 (d) lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level

3 (d) persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

Setting aside the reliability issues discussed earlier, it is clear that the presentations of these two children are very different. Yet they both receive a “diagnosis” of autistic disorder.

In fact, using the APA’s own polythetic formula, one could identify 2,091 different presentations that meet the DSM criteria for this “diagnosis.” Even if one allows that many of these presentations will be somewhat similar, it is clear that there is a great deal of heterogeneity built into this diagnosis.

PREVALENCE

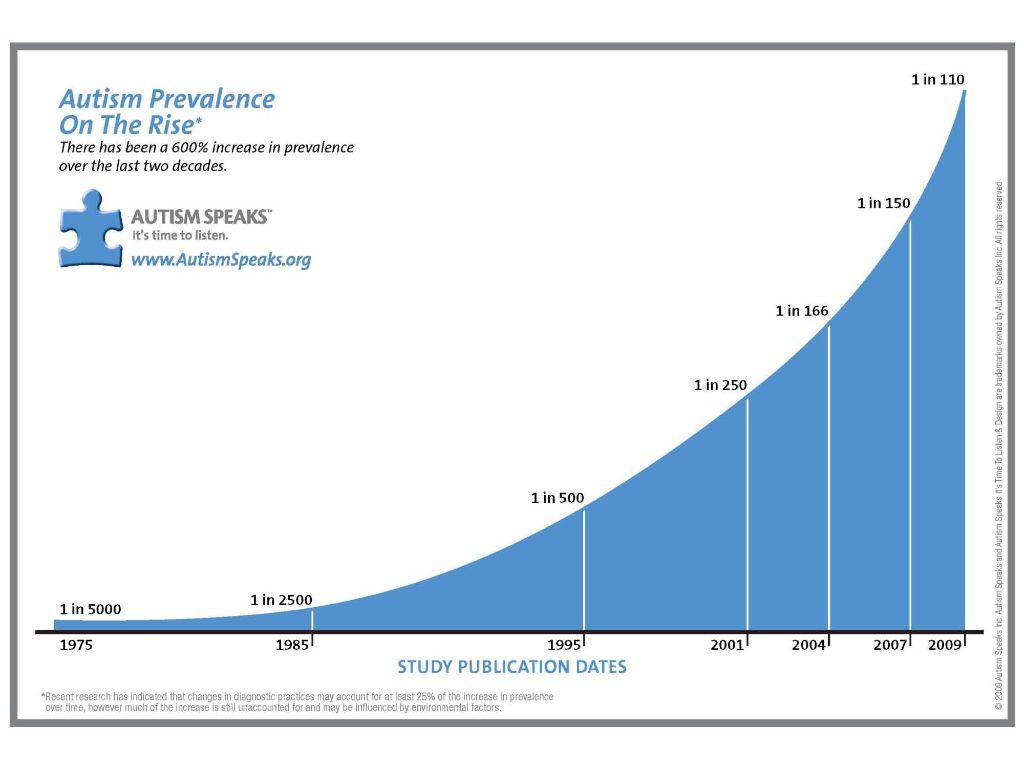

So let’s return to the question of prevalence. The overriding issue here is that the more vagueness in the definition of the phenomena in question, the more suspect are the prevalence estimates. Here’s the graph that Autism Speaks have generated.

Obviously the graph shows a steepening rise from earlier to later, and it’s tempting to ask the question: Does this reflect a real rise in prevalence? But the assumption here is that there is this “entity” called “real autism.” In fact, the only generally accepted definition of autism is (as far as I know) the one provided by the APA, and that, as we saw, is subject to various intrinsic problems.

The fact is that we can never say with certainty whether there is a real increase in prevalence until we define the problem much more closely. My guess is that any serious attempt to do this will reveal that in fact there is not one autism, but many. Or more accurately, that the various problems which today are loosely aggregated under the heading autism would be better conceptualized, and addressed, as several distinct problems.

SIGNIFICANCE OF PREVALENCE ESTIMATES

So what does Autism Speaks’ graph mean? Does it mean that there really has been a huge increase in the number of children with these problems, or does it simply reflect that more children are being assigned this particular label? People like Dr. Brogan say the former, and they blame vaccines and various environmental toxins. But it could also be argued that the increase is due to various forms of diagnostic creep, including extending the diagnostic net to include less severe cases. John McGowan’s point is that there is “much more emphasis on diagnosis now,” and this is undoubtedly true. We’ve certainly seen this phenomenon with the other mental health “diagnoses.”

I’m not aware of any study that has attempted to clarify this. In fact, I’m not even sure that such a study would be feasible. The past is gone forever.

According to Webster’s dictionary, the word “autism” was not in use prior to the 1940’s. Autism was not included as a separate entity in DSM-II (1968), but was mentioned simply as one of the characteristics of childhood schizophrenia. It certainly would not be possible to obtain prevalence estimates for that period.

Most of the steepness of the graph, however, occurs after 1995. And it really climbs after 2010! As I’ve mentioned earlier, the DSM criteria have a good measure of built-in vagueness, but has the vagueness increased that much since 1995?

It is a central theme of this website that the putative increase in “mental illness” prevalence generally is driven by disease-mongering and pharma-psychiatric marketing. And it is certainly possible the considerations of this sort underpin the autism figures. Some support for this position can be drawn from the report that “…approximately 45% of children and adolescents and up to 75% of adults with ASDs [autism spectrum disorders] are treated with psychotropic medications.” (Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. The American Academy of Pediatrics 2007) The drugs most commonly used are SSRI’s, neuroleptics, and stimulants.

So we’re still left with the question: is there really an increase in the numbers of children with these problems, or is the reported increase artifactual? With the information I’ve been able to find, I have to say: I don’t know.

Dr. Brogan says clearly that the increase is real, and is due to environmental toxin and vaccines.

Judith Mill, PhD, of the Center for Autism Research at Children’s Hospital, Philadelphia, says it’s both: “…contributing to the increased number of diagnoses is heightened awareness of subtle forms of ASD and broader application of the diagnostic criteria,…” and “…new data suggesting that 15 percent to 30 percent of autism cases may be due to the increasing average age of new fathers.” (Autism prevalence and the DSM, APA 2012)

Joel Paris, MD, expresses the view that the increase reflects the “…pathologizing of subclinical symptoms,” i.e. diagnostic creep. [The Intelligent Clinician’s Guide To the DSM-5, (2013), p 142]

With regards to Dr. Brogan’s contention that the APA’s revision of their criteria is a pharma-APA conspiracy to conceal the increasing prevalence, I have to say again that I don’t know. It’s a strong claim. I have no qualms asserting that psychiatry and the psycho-pharma industry routinely collaborate in disease-mongering, and in the marketing of drugs. But the assertion that they would collaborate to cover up the harmful effects of mass vaccination takes us to a different level. I’m not saying that it couldn’t happen. I just have no information to support the claim. In fact, I hardly know where to look. If anyone has any information or leads, I’d be glad to take a look.

There is, incidentally, a general expectation that the implementation of DSM-5 will indeed result in fewer diagnoses of autism. The APA has created a lesser “diagnosis” – social communication disorder – to accommodate the less severe presentations. How all this will work out in practice remains to be seen. It is unusual, I think, to see the APA making one of their “diagnoses” more restrictive. Their agenda since the first DSM has always been expansion.