On November 12, 2013, Molecular Psychiatry published online Evidence that duplications of 22q11.2 protect against schizophrenia, by Rees et al. The print version was published last month – January 2014.

Here’s the authors’ summary:

“A number of large, rare copy number variants (CNVs) are deleterious for neurodevelopmental disorders, but large, rare, protective CNVs have not been reported for such phenotypes. Here we show in a CNV analysis of 47 005 individuals, the largest CNV analysis of schizophrenia to date, that large duplications (1.5–3.0 Mb) at 22q11.2—the reciprocal of the well-known, risk-inducing deletion of this locus—are substantially less common in schizophrenia cases than in the general population (0.014% vs. 0.085%, OR=0.17, P=0.00086). 22q11.2 duplications represent the first putative protective mutation for schizophrenia.”

The idea of a genetic mutation that would protect one from schizophrenia aroused a good deal of interest and enthusiasm.

Schizophrenia Research Forum, for instance, ran the headline Protection From Schizophrenia – Too Much 22q11.2 is a Good Thing on an article dated November 22 2013, and Genetic protection Against schizophrenia on another article on the same date.

The Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative used the headline Duplication of chromosome 22 region thwarts schizophrenia on a January 2, 2014, piece.

The Rees et al paper has added some impetus to psychiatry’s claim that the condition known as schizophrenia is a genetic disease and, for this reason, I thought it might be helpful to take a closer look at the study.

Let’s start by examining what the authors’ summary actually says.

Copy number variants (CNVs) are essentially sections of the DNA string that contain variations from normal. The DNA is the “blueprint” of the organism, so variations in the string always have the potential to cause variations in the structure of the organism.

There are two kinds of CNVs: deletions and duplications. In deletions, a small piece of the normal code is omitted; in duplications, a piece is inserted twice.

When the authors write that a number of CNVs are deleterious for neurodevelopmental disorders, what they mean is that there is an association between having the CNV and having the disorder. Rees et al focused on the part of the genome designated 22q11.2: a small section near the middle of chromosome 22.

DELETIONS

Deletions in the 22q11.2 area are associated with numerous features, ranging both in number and severity. These features include: heart disease; palate abnormalities; unusual facial features; learning difficulties; renal abnormalities; hearing loss; autoimmune illnesses; etc… 22q11.2 deletions are also associated with autism and low IQ in childhood, and with “schizophrenia” in later years. The condition is called DiGeorge syndrome.

About 5% of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome cases are inherited. The remaining are new mutations, and arise because this DNA region is vulnerable to rearrangement when sperm and ovum cells are being formed. The precise mechanism by which 22q11.2 deletions cause the various birth defects mentioned above is unknown, but is believed to involve structural anomalies in the embryonic pharyngeal area, which in turn cause defects in the thymus and parathyroid glands.

22q11.2 DUPLICATIONS

Duplications on 22q11.2 are associated with low IQ, learning problems, psychomotor delays, and growth retardation. The mechanism by which the duplications produce these problems is unknown.

In addition, duplications on 22q11.2 can be inherited from a parent whose development has been normal, so there is not a clear one-to-one relationship between the syndrome and the genetic duplication.

THE REES ET AL STUDY

The Rees et al study searched for 22q11.2 duplications in a sample of 6,882 individuals who had a “diagnosis of schizophrenia,” and in another group of 11,225 individuals drawn from four non-psychiatric data sets.

Their results are summarized in the table below:

| Schizophrenia | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Duplication | 0 | 10 |

| No duplication | 6,882 | 11,245 |

| Total | 6,882 | 11,255 |

On the face of it, this result looks impressive. Of the 6,882 cases with a “diagnosis” of schizophrenia, there were none that had a duplication on 22q11.2. And so it might be argued, and indeed is being argued, that the genetic duplication in question protects one from becoming schizophrenic.

However, if we look at the right side of the table, we see that only 10 individuals out of the 11,255 controls actually had the duplication. So even if we assume that the study is methodologically sound, and that schizophrenia vs. non-schizophrenia is a valid dichotomy (which, incidentally, it isn’t), it is clear that only a tiny fraction (less than 1 in 1000) of the controls owe their “illness-free” status to 22q11.2 duplication.

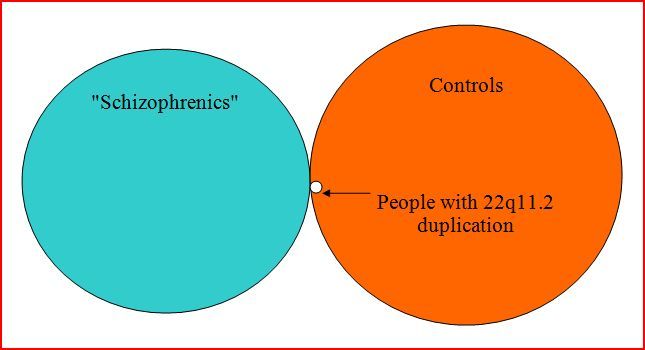

This can be seen more readily if the data is viewed diagrammatically as below. The areas of the circles represent the sizes of the three groups: those with “schizophrenia” (blue); the controls (orange); and those with the genetic duplication (white). All of the latter group fall within the controls’ circle, but are still a tiny part of that group.

Incidentally, Rees et al report that their result is statistically significant (p = 0.017). What this means is that the way the ten people with duplications are distributed (i.e. 10 in the control group and none in the “schizophrenic” group) has only a 1.7% chance of being a random fluctuation. In other words, it is probably a genuine skew. But it is also a very small effect. The statistical significance of a result is largely a function of the sample size, and is not indicative of the magnitude of the effect. On the basis of this study, for instance, one could tentatively conclude that there is an association between having the genetic duplication and not having a “diagnosis” of schizophrenia, but that the association is very weak. The putative protection factor applies to fewer than one person in a thousand.

Rees et al continued their study by obtaining and combining more cases from other CNV data sets. They obtained 22q11.2 duplication data on an additional 14,256 “schizophrenia” cases and 14,612 controls. They found essentially the same association, but again the association was weak.

| Schizophrenia | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Duplication | 3 | 12 |

| No duplication | 14,253 | 14,600 |

| Total | 14,256 | 14,612 |

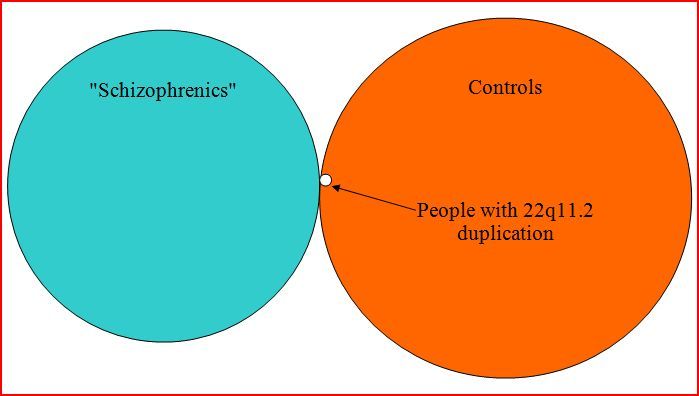

Or expressed diagramatically:

[Note: In this diagram, a small segment (3/15) of the duplication circle should be in the blue circle, but MS Word draw function wouldn’t cooperate. Or perhaps I wasn’t cooperating with MS Word?]

Next the authors combined the two sets of data to produce the following overall result:

| Schizophrenia | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Duplication | 3 | 22 |

| No duplication | 21,135 | 25,845 |

| Total | 21,138 | 25,867 |

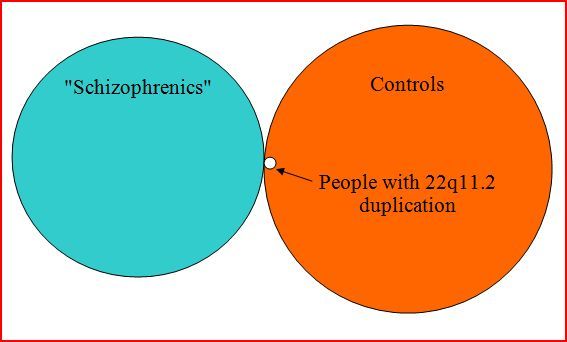

Diagramatically:

[Note: Again, a small section of the duplication circle should be in the “schizophrenic” region.]

DISCUSSION

Perhaps the most obvious point that needs to be made is that the DNA is the organism’s blueprint, and as such it determines how the organism will be formed (two eyes, two hands, one heart, etc.); the spatial arrangement of these parts; and the material (bone, muscle fiber, etc.) from which these parts will be made. The DNA determines the organism’s structure.

Links between the DNA and the organism’s activities are always mediated by one or more intervening factors. This is important in the present context because the condition known as schizophrenia is – by definition – a cluster of activities in which the person engages.

To illustrate this, let’s consider polycystic kidney disease (PKD). This is a good example, because it is a clear-cut genetic illness caused by cysts in the kidneys. The cysts block the flow of blood through the kidneys, and, as the cysts proliferate and grow larger, the kidneys are destroyed.

The cysts are caused by a defective gene. (Actually there are two, possibly three, genes that can produce PKD, but about 80% of cases arise from the gene PKD-1, and for the sake of simplicity, we’ll confine our attention to that.) A gene, incidentally, is a piece of the DNA string – a piece of the organism’s blueprint. In polycystic kidney disease, the PKD-1 gene conveys faulty instructions concerning the walls of the tiny tubes (nephrons) in the kidneys. Instead of calling for ordinary nephron epithelium in these locations, PKD-1 calls for cyst wall epithelium. And cyst wall epithelium produces fluid which accumulates in, and ultimately destroys, the nephrons and the kidney.

So the gene determines the structure of the nephron wall. This structure in turn causes the cyst wall epithelium to produce fluid. This activity is a direct effect of the structure. Secondly, as the nephrons become increasingly blocked, the kidneys produce less urine. So, reduced urination is a secondary functional effect of the gene PKD-1. Thirdly, a child growing up with polycystic kidney disease is, other things being equal, likely to feel sick and under-the-weather much of the time, particularly if the disease has not been recognized and remedial/palliative measures have not been taken. Such a child, again other things being equal, is likely to be fussier and more tearful than other children, and it is entirely possible that one could find a weak correlational link between gene PKD-1 and childhood fussiness, though, of course, any search for such a correlation will be confounded by the obvious fact that children can be habitually fussy for other reasons.

And from there the causal chain could continue in various ever-weakening directions. For instance, the child might become somewhat sad and despondent. Or it could be that the child received extra attention and comforting from his parents and was fairly content, and so on. Ultimately the outcome is impossible to predict with any kind of precision, and the best we can expect from genes vs. subsequent behavior studies are weak, tenuous correlations.

With regards to the very weak inverse link between 22q11.2 duplication and the condition known as schizophrenia, we can barely speculate as to the nature of the casual sequence, because it is not known how 22q11.2 duplication expresses itself in the organism structurally. The authors state that 22q11.2 duplication is positively associated in children “…with a wide range of psychiatric and behavioral abnormalities…including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism, as well as other social and behavioral problems,” and they cite various references in support of this statement. So what we’re left with from Rees et al is that 22q11.2 duplication is positively associated with low IQ and with various psychiatric and behavioral problems in childhood, but, by contrast, is negatively associated with a “diagnosis” of schizophrenia in adulthood.

A “diagnosis” of schizophrenia hinges on complex social activities that arise relatively late in life, and cannot be direct effects of a genetic anomaly, or even several anomalies. To illustrate this, let’s go back to the 22q11.2 deletions discussed earlier. I mentioned that deletions in this DNA segment are associated with various problems, including palate abnormalities. The palate abnormalities are a direct effect of the gene defect. One of the palate abnormalities associated with these deletions is cleft palate. This condition, if not corrected surgically, results in a characteristically strained and nasal speech quality, which in severe cases can be quite stigmatizing.

The cleft palate is a direct effect of the deletion; the nasal speech is a secondary effect of the deletion.

Children with this kind of speech are sometimes mocked and bullied by their peers. The child might react to this kind of stigmatizing by becoming violent, or by withdrawing socially, or by speaking as little as possible, or in various other ways. These reactions would be considered tertiary effects of the deletion. And so on. Each step in the chain takes us further from the genetic anomaly, and the statistical associations grow commensurately weaker. In the case of a child who became violent in response to the taunting, it would be stretching the matter to say that the violence was caused by 22q11.2 deletions. Nor would one conclude that the child’s violent acts were symptoms of a genetic disease. In fact, conceptualizing the child’s violence or social withdrawal as a symptom of 22q11.2 deletion would generally be considered nonsensical. And this is true even though the link between the deletion and the cleft palate is clear-cut and direct.

In the same way, it is simply not tenable to claim that “schizophrenic” behaviors (e.g. disorganized speech) are symptoms of a genetic disease. This is particularly the case in that correlations between the diagnosis and genetic anomalies are typically very small, and the so-called illness doesn’t usually emerge until age 20 or later. The effects of any genetic anomalies that might be correlated have had ample opportunity to be modified and shaped by social and environmental factors, and in the absence of a clear and readily understandable link between the “symptom” and a genetic defect, the social and environmental factors are more credible causal constructs.

“Schizophrenia” is not a unified condition. Rather, it is a loose collection of vaguely defined behaviors. For this reason, any genetic research done on this condition will inevitably result in conflicting and confusing results. It’s like looking for genetic similarities in all the people who play scrabble, or cheat on their taxes, or collect postage stamps, or whatever. If the sample sizes are large enough, one could probably find small effects in all or most of these areas, but no one would conclude from this that these are genetically determined activities.

A person’s ability to learn depends on two general factors: a) the structure of his brain, as determined by his DNA, and b) his experiences since birth.

One can’t learn to play the guitar, for instance, unless one has adequate neural apparatus, and fingers, both of which require appropriate DNA coding. But even though a person’s genetic endowment might be excellent in these regards, he will never learn to play unless he is exposed to certain environmental factors. In the same way, a person whose genetic endowment was fairly marginal might become an excellent guitarist with the correct environmental encouragement and support.

Similar reasoning can be applied to the behavior of not-being-“schizophrenic.” This behavior involves navigating the pitfalls of late adolescence/early adulthood with a modicum of success, and establishing functional habits in nutritional, interpersonal, occupational, and other important life areas. Clearly it requires adequate neural apparatus, hence the weak correlations with genetic material, but equally clearly it requires an appropriately nurturing childhood environment, with opportunities for emotional growth and skill acquisition.

Given all of this, it’s not surprising that researchers are finding correlations between DNA variations and a “diagnosis” of schizophrenia, but given the number of links in the causal chain and the multiplicity of possible pathways at each link, it is also not surprising that the correlations are always found to be weak.

It is not my purpose to disparage genetic research. In my view it is an extraordinarily promising field that holds the potential to find causes and cures for various illnesses. In the behavioral field, however, it is being overemphasized at the expense of less dramatic, but ultimately more promising socio-behavioral work. Looking for the genetic causes of behavioral/emotional problems is a bit like studying the blueprint of a car in an attempt to discover why there is a dent in the fender. This is a particularly apt analogy, in that if one studied a very large number of dents in different vehicles, one would probably discover a weak correlation between the depth of the dent and the thickness of the steel used in the car’s manufacture. And this thickness would, of course, be shown on the car’s blueprint. So there will be a small correlation between an entry on the blueprint and the size of the dent, and this is analogous to the small correlations found between genes and subsequent behavioral problems.

But if we truly want to know why there is a dent in the car’s fender, it might be more fruitful to simply ask the owner.