In November 2013, the journal Schizophrenia Research published a paper by Tsuji, T. et al. titled Premorbid teacher-rated social functioning predicts adult schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: A high-risk prospective investigation. Here’s the abstract:

“Social functioning deficits are a core component of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and may emerge years prior to the onset of diagnosable illness. The current study prospectively examines the relation between teacher-rated childhood social dysfunction and later mental illness among participants who were at genetic high-risk for schizophrenia and controls (n=244). The teacher-rated social functioning scale significantly predicted psychiatric outcomes (schizophrenia-spectrum vs. other psychiatric disorder vs. no mental illness). Poor premorbid social functioning appears to constitute a marker of illness vulnerability and may also function as a chronic stressor potentially exacerbating risk for illness.”

The study was done in Denmark by a Danish-American team, as part of a large scale longitudinal developmental study. Studies of this sort are often done in Denmark, incidentally, because the Danes have a central mental health register and other data bases that facilitate the gathering of follow-up information.

The social functioning measure consisted of five items, each of which was rated on a five point scale. The total score was obtained by adding the five individual item scores. Lowest possible score was 5; highest possible score was 25. The items were:

1. The child does not seem to take part when the rest of the class is having fun.

2. The child has no friends.

3. The child is often teased.

4. The child does not actively seek friends.

5. The child seems to avoid contact with other children.

Here are some more quotes, interspersed with my comments:

“Results suggest that, even though many psychiatric difficulties are associated with deteriorations in social functioning, teacher-rated social deficits among school-age children appear to represent a marker of vulnerability specific to disorders within the ‘family’ of schizophrenia spectrum illnesses. These findings highlight the value of teachers in identifying key markers of risk such as social deficits.”

In the abstract quoted earlier, the authors acknowledge that “social functioning deficits are a core component of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.” [Emphasis added] With this in mind, it seems to me that the best and most parsimonious way to conceptualize the research finding is that children who have poor social skills will, in many cases, grow up to be adults with poor social skills. In particular, there seems to me no justification (other than psychiatric dogmatism) to conceptualize the matter in medical terms, and to impose a medical framework – “a marker of vulnerability” – on the data.

“Thus, social functioning has emerged as an important area for researchers interested in the core features of emerging psychotic illness…”

Here again, note the assumption of an “emerging…illness.”

“…results from this 48-year longitudinal record suggest that children on a trajectory toward schizophrenia-spectrum disorders demonstrate interpersonal deficits early in life, and that teachers provide valuable information regarding children’s social functioning.”

Again, note the medical language: children with poor social skills are “on a trajectory toward schizophrenia spectrum disorders.” The term “on a trajectory” also entails an element of inevitability, implying that children with poor social skills become psychotic in the same way that people who inherit the Tay-Sachs gene get the disease. Note also the identification of teachers as sources of “valuable information.”

A follow-up period of 48 years (1959-2007) is impressive in a longitudinal study, and it is likely that the findings will be afforded a high measure of credibility and status within the psychiatric community. A Google search on May 14 for the title got 7,770 hits. So the study is attracting attention.

In recent years, organized psychiatry has been actively promoting the notion of early intervention in schools and other settings for people who are considered “at risk” for acquiring a diagnosis of schizophrenia (e.g. here and here). The DSM-5 workgroup promoted the “diagnosis” of attenuated psychosis syndrome, as a means of identifying teens considered to be “at risk,” and this “diagnosis” is included in the manual as a specific example in the category: “Other Specified Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder 298.8” (p 122).

In this general context, a simple (5-item) teacher-completed social skills rating scale is likely to have considerable appeal. For these reasons, it seems important to subject the study to some scrutiny.

SOCIAL SKILLS AND “SCHIZOPHRENIA”

Perhaps the study’s most significant shortcoming is the one already mentioned: that poor social skills are in fact the primary defining feature of DSM-5’s “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.” The defining features of these psychiatric “diagnoses” are set out on pages 87 and 88 of the manual, and include the following, all of which fall, I suggest, under the heading of social skills deficits:

- reduction in the expression of emotions in the face

- showing little interest in…social activities

- diminished speech output

- lack of interest in social interactions

- childlike silliness

- lack of verbal…responses

- staring

- grimacing

- mutism

- echoing of speech

- switching topics

Even delusions and hallucinations, the cornerstones of these “diagnoses,” are closely connected to social skills. A child who grows up with poor social skills is often victimized and bullied, and quickly learns that the “real” world is not usually a source of joy or reward. The subsequent retreat into a private realm is not only understandable, but in many cases adaptive.

So when Tsuji et al. discovered, through their research, that children who are rated by their teachers as socially unskilled, have a better than average chance of attracting a “diagnosis” of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder in adulthood, all that they have found is that some individuals, who are socially unskilled as children, are socially unskilled in adulthood. Poor social skills is an inherent component of the definition of “schizophrenia.” The notion that this needs to be discovered as a “marker of vulnerability” is specious and misleading.

FALSE POSITIVES

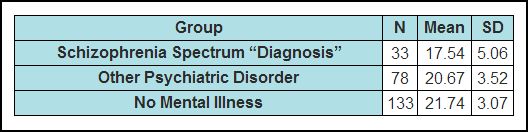

The study write-up is sparse in both description and data, so it’s not possible to subject the numbers to serious scrutiny. But it is clear that many of the participants who were rated poor on social skills during childhood grew up to have “no mental illness” in later life. The authors do tell us that the “…[s]ocial functioning scores ranged from 6 to 25 with an overall sample mean of 20.83 (SD = 3.78).” They also provide means and standard deviations for the three outcome groups.

It should be noted that the above table does not appear in the text, but was created by me from data presented as run-on text in three separate sections of the paper. (Higher scores mean better social functioning)

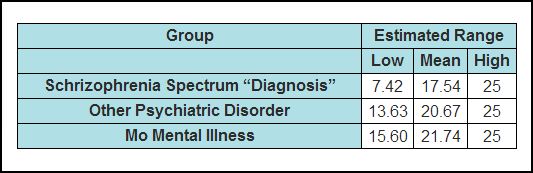

What’s immediately clear from this table is that there is considerable overlap in the social skills scores from the three outcome groups. We can get an estimate of the range of the three groups from the standard deviations. Most of the participants’ scores will lie in the range from two SD’s below the mean to two SD’s above the mean. So we can calculate tentative score ranges as follows: (The range for all scores was 6-25, so 25 is always the upper limit.)

It is reasonably certain that many of the low scorers in the NMI group scored below the mean of the schizophrenia spectrum group, and yet these individuals had never been assigned a mental illness “diagnosis” of any kind. It’s not possible to say, based on the published data, what the absolute numbers were, but given that the NMI group is four times larger (133 vs. 33) than the spectrum group, it is entirely feasible that there were as many, or even more, individuals in the NMI group scoring below the “spectrum” mean (17.55) as there were in the spectrum group. Using the spectrum mean (17.55) as a prognostic cutoff would have created the prediction that these individuals were on the so-called trajectory to a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. But in fact they acquired no mental health “diagnoses” at all. So using this social skills scale, or indeed any similar scale, is likely to “identify,” and target for psychiatric treatment, large numbers of individuals who in fact were “on a trajectory” to “no mental illness.”

And there’s another problem. Of the 33 individuals who received a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder in adulthood, only 18 of these had been assigned a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The remaining “diagnoses” were:

Psychosis NOS or delusional disorder 8

Schizotypal, paranoid, and schizoid personality disorder 7

The authors state that their decision to group these categories together was “…guided by familial research suggesting genetic links between the disorders…” However, it is entirely possible that the grouping was done to increase the size of the high “pathology” group in order to make the association seem more robust. It is also possible that the data was pre-examined and it was noticed that a large proportion of the poor-social-skills group had been assigned these other diagnoses in adulthood.

I have no way of knowing if any data massaging of this sort happened. But the decision to group the diagnoses in this way, coupled with the sparseness of data in the write up, raises questions. At the very least, it increases the chances of a predictive “hit” by the simple expedient of widening the target.

Another troubling aspect of the “diagnosis” grouping is that the authors are not using the term “schizophrenia spectrum disorders” in the same sense as DSM-5. In particular, the authors have included the conditions known as paranoid and schizoid personality disorders, neither of which is included in the DSM-5 grouping. This, I suggest, is important for two reasons. Firstly, most readers on coming across this term in the title and in the abstract, would have assumed that it referred to the DSM-5 category. At the very least, the authors should have stated explicitly that this is not the case – that in fact, they were using the term differently. Secondly, and more importantly, the behaviors entailed in the paranoid personality and schizoid personality labels are entirely a function of social skills. It is likely that individuals who meet these general descriptors would score very low on a social skills scale at age 11-13, and this may have been a major factor in depressing the overall score of the spectrum group.

Many credible accusations of data massage have been leveled at psychiatric researchers in recent years, and in this regard it would have been helpful if Tsuji et al. had published some more numerical data. Even the means and standard deviations of the “paranoid” and “schizoid” personality groups would have been useful.

PREDICTIVE VALUE OF THE RESULTS

As mentioned earlier, the title of the article is Premorbid teacher-rated social functioning predicts adult schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: A high-risk prospective investigation.

This, I suggest, is misleading. The social functioning risk ratio for no mental illness vs. spectrum disorders was only 1.31 (with a 95% confidence interval of 1.17 to 1.46). This does not indicate high predictive potential. To illustrate this, imagine 100 envelopes spread out on a large table; 50 red and 50 blue. A person is informed (truthfully) that half of the blue envelopes contain a $100 bill and the other half contain a go-to-jail-now card. With the red envelopes, the odds are better – 19 jail cards and 31 $100 bills. The person is invited to choose one envelope and open it. If it is a jail card, he will be incarcerated. If it contains a $100 bill, he gets to keep it. Obviously, other things being equal, he should choose a red envelope, but he still runs a 38% chance of going to jail, versus a 50% with the blue envelopes. The risk ratio for blue to red is about 1.31. So, yes, the color red does predict dollars over jail – but the potential for error (i.e., jail) is still high. Similarly, if a person were to use the five item social skills scale described in this study to predict a “schizophrenia spectrum disorder” in adulthood (odds ratio also 1.31), his prediction would be false a great deal of the time. The word “significantly” in the abstract refers only to statistical significance, and indicates that the result is unlikely to have occurred by chance. It has no bearing on the magnitude of the effect.

A more accurate title for the paper would be:

“Teacher-rated social functioning at age 10-13 (as measured by a five-item scale) is correlated modestly with acquiring a diagnosis of schizophrenia, or psychosis not otherwise specified or delusional disorder or schizotypal personality disorder or paranoid personality disorder or schizoid personality disorder, in adulthood.”

SOCIAL SKILLS

The great tragedy in this area is that poor social skills is an eminently remediable condition. Social skills can be taught as easily, and as readily, as counting, spelling, and playing simple games. Children, for instance, who are excessively boastful, which in later life will attract the label “grandiosity,” can be coached successfully to downplay their self-promotion and to pay compliments to others. Ordinary conversational skills such as making eye contact, admitting to mistakes, smiling, allowing others an opportunity to speak, etc., can all be coached without difficulty. Conscientious parents have been doing this since the dawn of civilization, and probably even earlier.

Unfortunately, however, in the present time this kind of teaching often doesn’t take place. While children who can’t count or read attract lots of remedial attention, the lack of social skills is somehow seen as an inherent defect that doesn’t lend itself to coaching. Social skills are often conceptualized, even by teachers, as an integral part of “the child’s personality,” or as indicators of “deeper” problems, rather than skills that can be acquired, practiced, and cultivated in the normal way. Children with deficits in this area are often sent to the mental health center, where they acquire various “diagnoses,” and are given the false and disempowering message that they are sick. The Tsuji et al. study will lend unwarranted credence and support to this practice, in that it will be used to promote the notion that these individuals are “on a trajectory” to a “schizophrenia spectrum disorder,” and that this “trajectory” can be altered only by timely psychiatric intervention.

It is also the case that some people, children and adults, don’t want to socialize. They prefer their own company, and often excel in various non-social areas. The present drive towards “early intervention” will pathologize these individuals, and will draw them into psychiatry’s disempowering and destructive net – for their own good, of course.

AUTHORSHIP

Although Thomas Tsuji (a sixth-year grad student in the UBMC Department of Psychology) is shown as first author, it is clear the Jason Schiffman, PhD, is the principal investigator. Under the heading “contributors,” the article states: “Dr. Schiffman formulated, conducted, and/or oversaw the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and manuscript preparation.” Dr. Schiffman is also listed as the “corresponding author,” with an address at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). You can see his UMBC bio here. His listed research interests are: “Early identification and treatment of youth at risk for psychosis. Reduction of stigma against people with serious mental health concerns.”

Some of Dr. Schiffman’s recent research publications are also listed. Here are two quotes from these studies:

“Brief self-report questionnaires that assess attenuated psychotic symptoms have the potential to screen many people who may benefit from clinical monitoring, further evaluation, or early intervention.” (here)

“The validation of attenuated symptoms screening tools is an important step toward enabling early, wide-reaching identification of individuals on a course toward psychotic illness.” (here)

Dr. Schiffman is also on the staff of the Center for Excellence on Early Intervention for Serious Mental Illness. This agency was created last year by a $1.2 M grant from the State of Maryland as part of the state’s response to the problem of mass shootings in schools and other locations. The center is headed by Robert Buchanan, MD, a professor of psychiatry at University of Maryland. Dollars for Docs indicates that Dr. Buchanan received $34,520 from pharma in the period 2009-2012. Information on the Center’s activities to date is sparse, but I did find two Baltimore Sun articles about the Center. The first article, titled New Maryland mental health initiative focuses on identifying and treating psychosis by Jonathan Pitts, was published on October 21, 2013. Here are two quotes:

“Research has shown those who eventually develop psychosis have often exhibited early warning signs, clues that give family members, teachers, health-care providers and others a chance to intervene early, if only they know what to look for.”

“The Clinical High-Risk program will be contacting schools, houses of worship, law enforcement and other communities that come into contact with youth to promote public awareness about such signs, Schiffman said, and clinicians will be available to provide testing and offer treatment options.”

The second article, written by Jean Marbella, was published on March 21, 2014. It’s titled UMBC study among efforts to increase awareness of mental illness. Here are some quotes:

“‘Many of the folks who need help get lost somehow,’ said Jason Schiffman, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County who is heading the study. ‘There are so many kids and young adults who slip through the cracks.'”

“Schiffman has long been interested in early intervention and de-stigmatization programs for those suffering mental health problems, but more recently, his work is benefiting from a new focus on the role such illnesses may have played in some shootings.”

And perhaps most telling of all:

“‘As a society, if we normalize the seeking of help,” he said, “people are more likely to seek that help.'”

There is it: psychiatry for all. A “diagnosis” for every problem and a pill for every “diagnosis.”

SUMMARY

And so it goes. Psychiatry, reeling under an ever-increasing barrage of criticism, has taken nothing on board with regards to its spurious concepts and its destructive treatments. Instead, it has hired a PR firm to polish up its image, and is actively cultivating the media and the politicians, with a view to embedding its concepts and practices more deeply into the legal and social fabric of our society. It is also exploiting shamelessly the public concern about the mass murders to promote its own expansionist agenda, indifferent to the stigmatizing effect that this will have on millions of innocent, socially isolated teenagers..

A great deal of their present effort is directed at two main themes: integration of psychiatry with primary care (a mental health worker in every GP’s office), and early intervention. Watch out for media infomercials on these topics in your local newspapers, and for bills on these topics in your statehouses. And please speak out. Early intervention is just a catch-phrase to sell more drugs to children and to destroy more lives.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

DISCLAIMER

In critiquing a paper like Tsuji et al., it is difficult to avoid using psychiatry’s terminology. My use of the terms “schizophrenia,” “schizoid personality disorder”, “schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” etc. should not be taken to imply any endorsement on my part of the validity of these concepts. On the contrary, the central theme of this website is that these terms have no ontological or explanatory significance, and are nothing more than loosely defined labels which psychiatry uses and promotes to legitimize the prescription of psychiatric drugs.