On October 23, Simon Wessely, MD, a British psychiatrist, published an article, The real crisis in psychiatry is that there isn’t enough of it, at the online site The Conversation. Dr. Wessely is the Professor of Psychological Medicine at King’s College, London, and is also the President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

The Conversation is an independent non-profit online media outlet that delivers “…news and views from the academic and research community…” directly to the public. Their aim is “…to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues.”

Here are some quotes from Dr. Wessely’s article, interspersed with my comments and observations.

“Psychiatry is apparently in crisis – again. On the one hand, psychiatrists are agents of social control, carrying out society’s bidding to ensure that the socially deviant are kept locked up out of sight and mind. And, despite having little idea of what causes the disorders they claim to treat (which some critics claim don’t exist), they remain set on medicalising more and more aspects of human existence. More still, psychiatry is a pawn of the pharmaceutical industry, peddling drugs that either don’t work or make you worse.”

This is Dr. Wessely’s first paragraph, and is as interesting for its general tone as for its content. The three links in the paragraph are to articles by:

- David Pilgrim, Professor of Health and Social Policy at the University of Liverpool

- Kate Kelland, a Health and Science Correspondent with Reuters

- John Read, Professor of Psychology at the University of Liverpool

All three articles are cogent, well-written, and relevant, and all three raise serious concerns about psychiatry; concerns which Dr. Wessely, as president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, might reasonably be expected to address.

Instead, he dismisses these articles in a mocking tone. And watch where he goes next:

“The thing is, none of these claims are either new, or radical. Look up ‘psychiatry in crisis’ on Google. And then stand well back. Since I started my psychiatry training in 1984, not a year has passed without a clutch of articles, papers and opinion pieces discussing this ‘crisis’. A random selection of articles shows that we have been in crisis because of recruitment (1982), lack of political clout (1984) and public image (1985). In 1997 The Lancet published an article on perceived biological bias. A few years later in the British Journal of Psychiatry it was for not being biological enough … You get the picture.”

In other words: we’ve heard it all before, and we’ll take no more cognizance of the present criticisms than we’ve taken of those that came earlier. Criticism of psychiatry is just part of the turf – not anything that needs to be taken seriously.

And incidentally tucked away in the Lancet article that Dr. Wessely so glibly dismisses, you’ll find this:

“In 1896, Emil Kraepelin rejected his previous adherence to a biologically based psychiatry when he urged his readers to shun disease categorisation and return to the richness of simple clinical observation: ‘As long as we are unable clinically to group illnesses on the basis of cause, and to separate dissimilar causes, our views about etiology will necessarily remain unclear and contradictory’.” [Emphasis added]

What Dr. Kraepelin – who incidentally is biological psychiatry’s historic hero – is stating here is that psychiatric “diagnoses” are simply labels with no explanatory value. This is perhaps the central criticism of those of us on this side of the debate, and is as true today as it was in 1896. But psychiatry has consistently refused to address, or even acknowledge, this matter.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

PSYCHIATRIC DETENTION

On the matter of psychiatric detention, Dr. Wessely acknowledges that this happens, but points out that “…only 1.2% of those being managed by psychiatric services were detained.” But watch where he takes this:

“Any humane society has a duty to try and look after its citizens when, as a result of a mental disorder, they pose a serious risk to themselves or others. And if this is the case, then it is better that it is sanctioned by law and implemented by health professionals, rather than by vigilantism and mobs. True, we don’t have the balance right yet, but not in the way the ‘crisis’ lobby would have you believe. Take jail, for example, there are far too many people in prison with serious mental illness – not too few.”

So, people are involuntarily committed when “…as a result of a mental disorder, they pose a serious risk to themselves or others.” The phrase “…as a result of a mental disorder…” presupposes that psychiatric diagnoses have explanatory value. To clarify this, consider the hypothetical conversation:

Family member: Why is my mother so depressed? Why does she want to kill herself?

Psychiatrist: Because she has an illness called major depressive disorder. The illness causes the depression and the suicidal tendencies.

Family member: How do you know she has this illness?

Psychiatrist: Because she is so depressed and wants to kill herself!

In other words: your mother is depressed and suicidal because she is depressed and suicidal.

This is the central flaw in psychiatry’s sand castle: there is no evidence for its diagnoses other than the very behavior that these “diagnoses” purport to explain. Psychiatric diagnoses have no explanatory value. This is what Thomas Insel, MD, Director of the NIMH, meant in his blog post Transforming Diagnosis when he said that the DSM is:

“…at best, a dictionary, creating a set of labels and defining each.”

But Dr. Wessely trots out the standard formula – “as a result of a mental disorder” – and dismisses this entire issue with customary psychiatric arrogance. And he attempts to obscure this logical fallacy by couching it within the framework of the duties of a “humane society”. In this regard, it is worth pointing out that psychiatric “management” of those who “pose a serious risk to themselves or others” has not been consistently humane, as is evident from the accounts of survivors.

But Dr. Wessely is only warming up. He tells us that legally sanctioned psychiatric care for those involuntarily detained is better than “vigilantism and mobs”. This is spin of a very high order. Firstly, Dr. Wessely’s words imply that these are the only two options: psychiatrists or mobs; and but for the staying hand of psychiatry, the mobs would be roaming the streets dragging these individuals from their homes and – what? – hanging them from lampposts? Secondly, he’s conveying the impression that those of us on this side of the debate who seek to undermine psychiatry’s “humane” efforts in this area are in fact promoting mob violence!

Dr. Wessely concedes that psychiatry doesn’t have “…the balance right yet, but not in the way the crisis lobby [that’s us, by the way] would have you believe”. The next sentence is obscure, but from the context, he seems to be saying that there needs to be more use made of involuntary detention, and that many of the people who should be in psychiatric detention are actually in prison (“…there are far too many people in prison with serious mental illness – not too few.”)

So, if I understand the passage correctly, people with “serious mental illness” who commit crimes should be diverted from the justice system to the psychiatric system.

In support of his contention, Dr. Wessely cites a brief report from the Prison Reform Trust which provides the following statistics:

- 14% of women and 7% of men serving prison sentences have a psychotic disorder

- 26% of women and 16% of men said they had received treatment for a mental health problem in the year before custody

- 62% of male and 57% of female prisoners have a personality disorder

- 49% of women and 23% of male prisoners have anxiety and depression

- 46% of women prisoners reported having attempted suicide at some point in their lives

And from these statistics, Dr. Wessely concludes that far too many people with “serious mental illnesses” are in prison. Firstly, note his injection of the word “serious”, which is not found in the PRT’s report. Secondly, we are routinely assured by psychiatry that at any given time, fully 20% of the population meets the DSM criteria for a mental illness, and that the lifetime figure approaches 50%. So it’s no great wonder that a great many people in prison also meet these criteria. Thirdly, one of the DSM’s personality disorders is antisocial personality disorder, which essentially means: habitual lawlessness and disregard for the rights of others. Is it surprising that these individuals are over-represented in prisons? Fourthly, the criteria for several “mental illnesses” include acts of violence, anger, defiance, etc… (e.g. conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, PTSD, etc.) and, again, it is scarcely surprising that many of these individuals are in prisons. Fifthly, prisons are – and are designed to be – depressing, anxiety-provoking places. Why should we be surprised to find that inhabitants of these places are anxious and depressed? And sixthly, a great many people in prison seek drugs to take the edge off their understandable sense of helplessness and distress. In this regard, they have two options: run the risk of smuggling in street drugs, or go see the prison psychiatrist and get some pharmaceutical products. The second option, of course, entails a “diagnosis of mental illness.”

But over and above these demographic issues, there is an unspoken assumption in Dr. Wessely’s contention, that people who meet the criteria for serious mental illness should not be held accountable for their criminal activity in the same way that other people are. I realize that this issue is intertwined with the more fundamental question of the efficacy and morality of imprisonment, but a discussion of this would take us too far afield. At the present time, imprisonment is the procedure routinely used in western countries as punishment for serious crime, and Dr. Wessely seems to be endorsing the belief that this procedure should not be used in cases where the miscreant meets the criteria for a “serious mental illness.”

Dr. Wessely provides no argument for this assertion, but presumably his “logic” would go something like this:

Question: Why did this individual commit this act of violence?

Answer: Because he has a mental illness called……

Question: How do you know he has this mental illness?

Answer: Because, among other things, he is given to acts of violence.

So we’re back to the same circular nonsense that we saw earlier. And Dr. Wessely appears to have no appreciation of the fact that his casual assertions are underpinned and driven by such fallacious reasoning. He has bought the psychiatric philosophy, hook, line, and sinker, and clings to its mantras with the blind faith of a true zealot. And with the faith of a true zealot, he trivializes and dismisses the protests of his critics, and with each assertion mires himself deeper in error.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

TREATMENT AND CAUSES

Remember that the title of Dr. Wessely’s paper is an assertion that we need more psychiatry, so he now embarks on the arduous task of showing how helpful and efficacious psychiatry is.

“Treatments are certainly far from perfect. But no more than in the rest of medicine; a recent review showed that treatments used by psychiatrists, both physical and psychological, compare well to treatments in routine use in other branches of medicine.”

This quote includes a link to a British Journal of Psychiatry article Putting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: review of meta-analyses by Leucht et al. The first thing that the observant reader might notice is that although Dr. Wessely asserted that psychiatric treatments both physical and psychological compare well to those in general medicine, there is no reference in the Leucht et al title to anything other than treatment with “medication”. And the title is not deceptive. Leucht et al runs to nine pages, with several additional supporting documents online, but there is no reference anywhere to any kind of treatment other than drugs. So when Dr. Wessely asserts that the Leucht et al study shows that psychiatric treatments, physical and psychological, compare well to those used in general medicine, he is making a false assertion. And besides, how many psychiatrists are using psychological treatments?

Here are the results of Leucht et al as written by the authors:

“We included 94 meta-analyses (48 drugs in 20 medical diseases, 16 drugs in 8 psychiatric disorders). There were some general medical drugs with clearly higher effect sizes than the psychotropic agents, but the psychiatric drugs were not generally less efficacious than other drugs.”

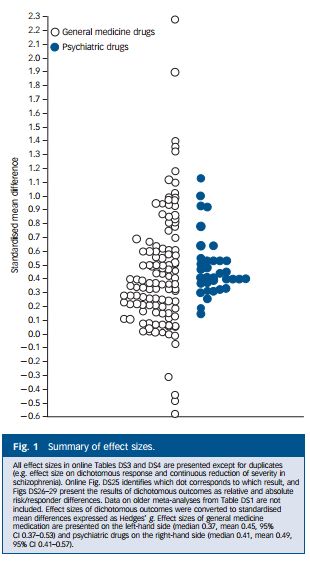

And here’s a schematic of the results:

Each circle represents a study. The vertical scale is the effect size (drug vs. placebo) expressed as a standardized mean difference. A score of zero means no drug effect; a negative score indicates that the drug did worse than the placebo; and a positive score indicates that the drug did better than the placebo. As can be seen, the results for both general medical drugs and for psychiatric drugs cluster around the 0.4 – 0.5 area, i.e. a positive difference of about half a standardized mean difference.

Each circle represents a study. The vertical scale is the effect size (drug vs. placebo) expressed as a standardized mean difference. A score of zero means no drug effect; a negative score indicates that the drug did worse than the placebo; and a positive score indicates that the drug did better than the placebo. As can be seen, the results for both general medical drugs and for psychiatric drugs cluster around the 0.4 – 0.5 area, i.e. a positive difference of about half a standardized mean difference.

A detailed critique of Leucht et al would take us too far afield, but the following points are worth noting:

- Most trials of psychiatric drugs use rating scales and other soft measures, which do not provide the kind of objectivity that characterize research in general medicine.

- It is generally easier for participants in psychiatric studies to identify whether they have been given the drug or the placebo, than is the case in general medicine. So the noted effectiveness of a psychiatric drug is more likely to be inflated by placebo contamination.

- Leucht et al specifically excluded any consideration of side effects, which in psychiatry frequently eclipse any reported drug benefits.

- Conflicts of interest. Both Stefan Leucht and Werner Kissling (one of the other authors) have received payments for consulting and lecturing from several pharmaceutical companies.

But back to Dr. Wessely.

“There remain doubts and uncertainties about the causes of many of the disorders we see. But this is not because we are ignorant, lazy or complacent; it is because psychiatric disorders, such as major depression, arise out of a complex set of circumstances – starting from your genetic inheritance, early upbringing, the relationships you make and the physical and psychological traumas and adversities to which you are exposed to in adult life. The issues with which we grapple are rarely simple or straightforward.”

The observant reader may notice that Dr. Wessely’s listing of the causes of major depression does not include neural chemical imbalance. This strikes me as odd, because in the past 30 years or so, every psychiatrist I’ve encountered has asserted confidently and vigorously that chemical imbalances in the brain were the only causes of depression. The impact of early upbringing, relationships, and the adversities of life were dismissed as irrelevant and distracting, and drugs were ladled out by the proverbial boatload to “cure” these supposed pathological imbalances.

Now, it may well be that Dr. Wessely has never been an adherent of the chemical imbalance school. It may be that, throughout his career, he has steered clear of this inane nonsense. But in the paragraph quoted above, it is clear that he is not speaking solely for himself, but rather for psychiatry in general. He refers to the disorders that “we” see; he assures us that “we” are not ignorant, lazy, or complacent; and he refers to the issues with which “we” grapple.

So from his assertions concerning psychiatry’s analysis of the complex genesis of depression, I can only conclude that, either Dr. Wessely is grossly out of touch with what’s going on in his field, or is primarily concerned with rewriting history.

And then:

“Not for us the simplicities of some other parts of medicine. Here is a cancer – take it out. There is a bug – kill it. In psychiatry, the ability to tolerate uncertainty is an essential skill. Because we have to negotiate fuzzy boundaries – between eccentricity and autism, between sadness and clinical depression, between hearing voices and schizophrenia – and there will always be boundary disputes.”

The simplicities of some other parts of medicine! “Here is a cancer – take it out”! “There is a bug – kill it”! Is this meant to be a serious description of general medicine? Frankly, it reads more like a Monty Python skit with John Cleese reciting the lines.

It is obvious that Dr. Wessely is caricaturing general medicine, which is founded on real science, in order to promote psychiatry, which is founded on unsubstantiated assertions and logical fallacies. And the notion of psychiatrists tolerating uncertainty strikes me as bordering on delusional. Psychiatrists in fact routinely challenge the open-mindedness of other professions in favor of their glib assertions concerning chemical imbalances and the restorative effects of their drugs and shock machines.

“Far from backing away from such debates, my experience of psychiatry is that we relish them.”

“If there is a little bit of crisis, like argument and discussion it keeps us on our toes, alert to new developments, and is an antidote to complacency.”

Obviously Dr. Wessely and I move in very different circles. The only “debating” I’ve ever heard from a psychiatrist could be paraphrased as: “We’re right; you’re wrong. And your position is damaging patients and increasing stigma.” And “Denying the existence of mental illness is like denying evolution or the Holocaust.”

THE EVIDENCE THAT MORE PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES ARE NEEDED

Dr. Wessely then provides his evidence that more psychiatric services are needed. This evidence is not based on any kind of comprehensive needs assessment. No demographic statistics are provided. No references to outcome findings. Dr. Wessely has no need of those kinds of complications. He knows that more psychiatrics services are needed because: he gets lots of letters from individuals who tell him so! “Not all letters I’ve received have been complimentary, but the main themes have not been about our services, but the lack of them.”

And from this evidence, Dr. Wessely confidently concludes:

“The real crisis in psychiatry is that there isn’t enough of it.”

And this is the same Dr. Wessely whose profession is noted for its “ability to tolerate uncertainty” and welcomes new developments “as an antidote to complacency”.

AND INCIDENTALLY

There are at least three studies that demonstrate a positive correlation between suicide rates and psychiatric expenditures.

Burgess P, Pirkis J, Jolley D, Whiteford H, Saxena S. Do nations’ mental health policies, programs and legislation influence their suicide rates? An ecological study of 100 countries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004 Nov-Dec; 38(11-12):933-9.

Results: “Contrary to the hypothesized relationship, the study found that after introducing mental health initiatives (with the exception of substance abuse policies), countries’ suicide rates rose.” [Emphasis added]

Shah A, Bhandarkar R, Bhatia G., The relationship between general population suicide rates and mental health funding, service provision and national policy: a cross-national study., Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010 Jul; 56(4):448-53. doi: 10.1177/0020764009342384. Epub 2009 Aug 3

Findings: “The main findings were: (i) there was no relationship between suicide rates in both genders and different measures of mental health policy, except they were increased in countries with mental health legislation; (ii) there was a significant positive correlation between suicide rates in both genders and the percentage of the total health budget spent on mental health; and (iii) suicide rates in both genders were higher in countries with greater provision of mental health services, including the number of psychiatric beds, psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses, and the availability of training in mental health for primary care professionals.” [Emphasis added]

Rajkumar AP, Brinda EM, Duba AS, Thangadurai P, Jacob KS. National suicide rates and mental health system indicators: an ecological study of 191 countries. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2013 Sep-Dec; 36(5-6):339-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.06.004. Epub 2013 Jul 17.

Results: “Significant positive correlations between suicide rates and mental health system indicators (p<0.001) were documented. After adjusting for the effects of major macroeconomic indices using multivariate analyses, numbers of psychiatrists (p=0.006) and mental health beds (p<0.001) were significantly positively associated with population suicide rates.” [Emphasis added]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CONCLUSION

Psychiatry is intellectually and morally bankrupt. Its concepts are spurious, and its “treatments” are destructive, disempowering, and stigmatizing. The conditions and problems that it purports to address are not illnesses, and are simply not amenable to remediation by psychiatric drugs. The temporary relief that these drugs afford some individuals is essentially similar to that obtained from alcohol and street drugs.

Psychiatry has no cogent response to these criticisms, and routinely relies on the kind of fatuous cheerleading exemplified in Dr. Wessely’s article, as a substitute for genuine debate.

I imagine that people expect more from the President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, but those of us on this side of the debate have long recognized that psychiatry, when all is said and done, has nothing cogent or substantive to offer.