On August 11, Pediatrics, the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, published an article by Amy Houtrow, MD, et al. The article is titled Changing trends of childhood disability, 2001-2011

Here are the authors’ conclusions:

“Over the past decade, parent-reported childhood disability steadily increased. As childhood disability due to physical conditions declined, there was a large increase in disabilities due to neurodevelopmental or mental health problems. For the first time since the NHIS began tracking childhood disability in 1957, the rise in reported prevalence is disproportionately occurring among socially advantaged families. This unexpected finding highlights the need to better understand the social, medical, and environmental factors influencing parent reports of childhood disability.”

The study was based on data derived from the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). This survey has been conducted annually since 1957, and involves interviewing a random selection of families concerning their health problems or concerns.

The present study examined responses for almost 200,000 children aged 0 to 17 in four time segments across the decade 2001-2011.

OVERALL PREVALENCE

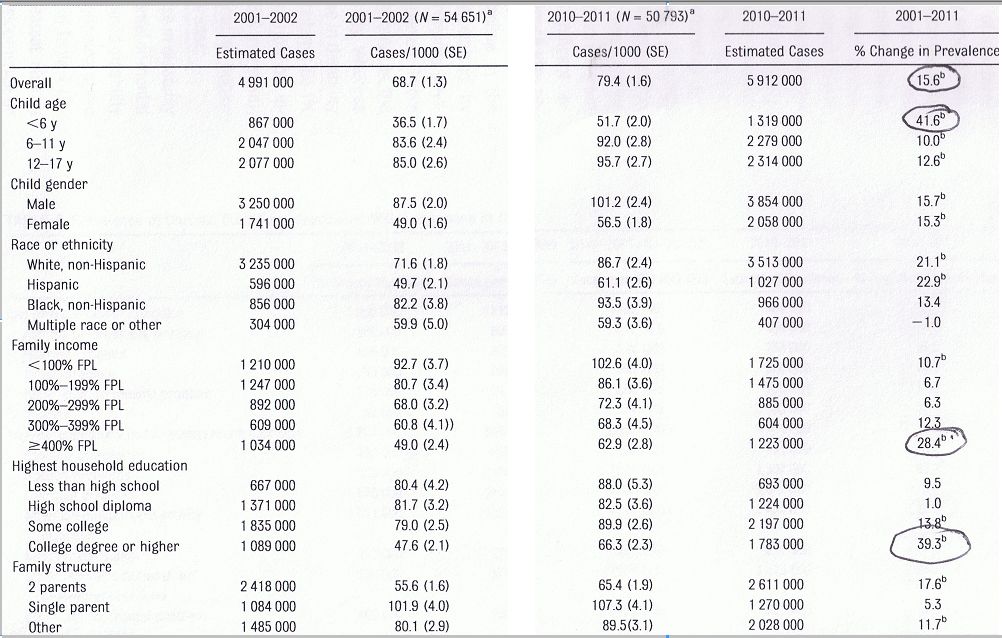

The prevalence of disabilities due to chronic conditions is given in Table 1.

Table 1 Prevalence of disabilities by sociodemographic characteristics, US children ages 0-17, 2001-2011

This table and Table 2 presented below have been altered from the corresponding tables that appeared in the Pediatrics article. Two central columns of data (for the periods 2004-2005, and 2007-2008) have been omitted for ease of presentation.

This table and Table 2 presented below have been altered from the corresponding tables that appeared in the Pediatrics article. Two central columns of data (for the periods 2004-2005, and 2007-2008) have been omitted for ease of presentation.

As can be seen, the overall prevalence of disability increased by 15.6% between 2001 and 2011. What’s surprising, however, is that the prevalence increased most for the highest earning group (i.e. 4 times poverty level and above). The increase for that group was 28.4%, whereas the increase for those earning below poverty level was only 10.7%. Note that the actual prevalence is still higher in the poorer group, 102.6/1000 vs. 62.9/1000 for the wealthier group. But the disability rate for the latter group is increasing at almost three times the rate as for the former.

Also noteworthy is the fact that disability prevalence for children of parents with college degrees increased by 39.3% for the decade, whereas the increase for children whose parents had a high school diploma was 1.0%, and for those whose parents had less than a high school diploma 9.5%.

The authors note that the high rates of increase in childhood disability in the more advantaged households was “unexpected.” They state:

“During the first 40 years of the NHIS, disability rates increased at similar rates for all income groups, with a clear social gradient where children from lower-income families were reported to have higher levels of activity limitations.”

PREVALENCE OF VARIOUS CONDITIONS

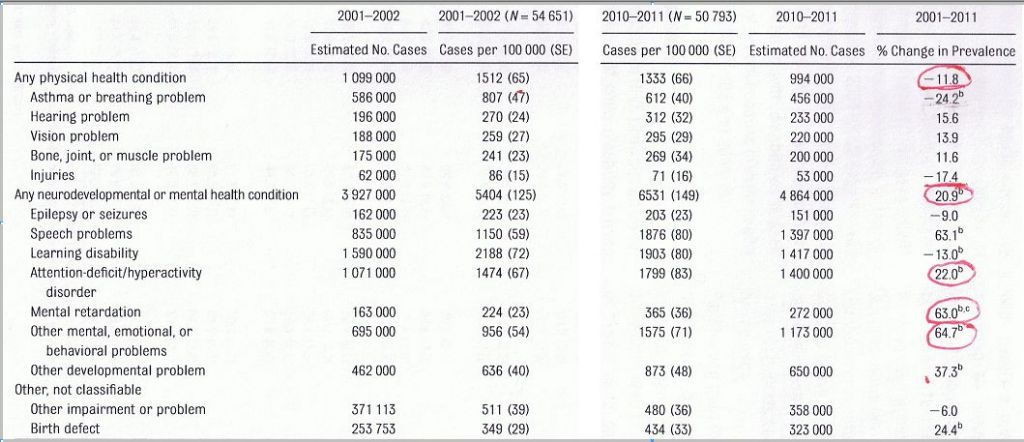

The prevalence figures for the various disability-linked conditions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Prevalence of chronic conditions associated with disabilities, US children ages 0-17, 2001-2011

The most striking piece of information in Table 2 is that although disabilities related to physical health conditions declined by 11.8% overall, disabilities related to “neurodevelopmental or mental health conditions” increased by 20.9%. The increase attributed to ADHD was 22.0%; mental retardation 63.0%; and other mental, emotional, or behavioral problems 64.7%.

The most striking piece of information in Table 2 is that although disabilities related to physical health conditions declined by 11.8% overall, disabilities related to “neurodevelopmental or mental health conditions” increased by 20.9%. The increase attributed to ADHD was 22.0%; mental retardation 63.0%; and other mental, emotional, or behavioral problems 64.7%.

The increase due to mental retardation is surprising. Almost all of the increase occurred in the period 2010-2011, and the authors suggest that it may be due to the change in terminology (from “mental retardation” to “intellectual disability”) that occurred about this time.

PREVALENCE AND SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS

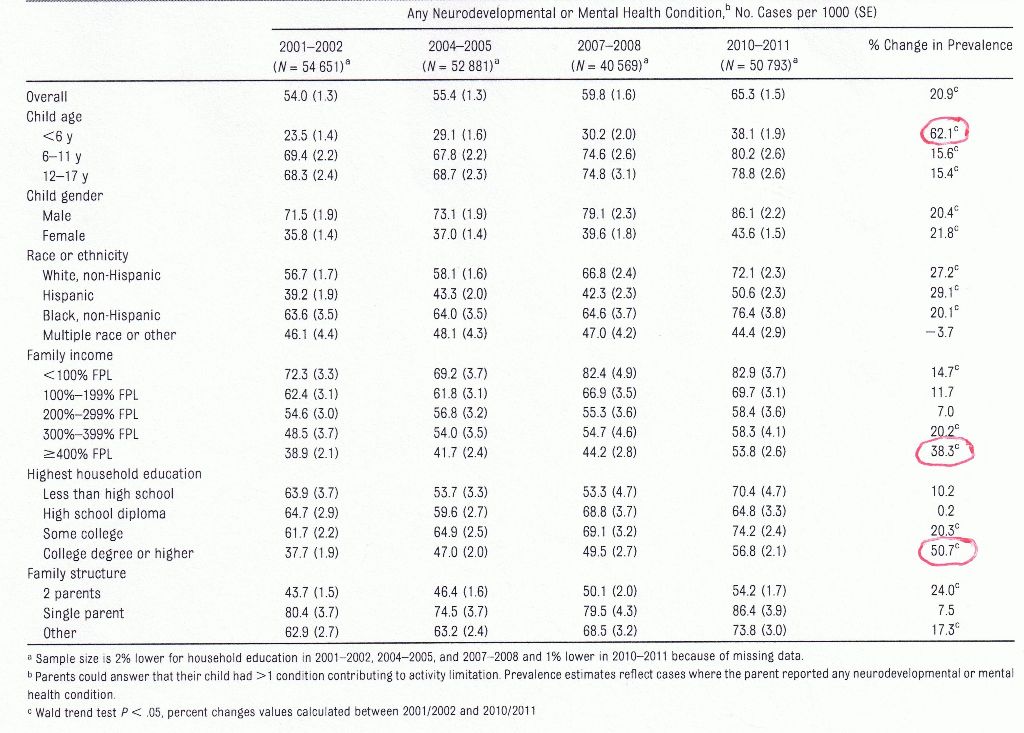

The authors then compared the mental/neurodevelopmental disability trends with the same sociodemographic variables shown in Table 1. Their results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Change in prevalence of neurodevelopmental or mental health conditions by sociodemographics, 2001-2011

And, again, we see the same pattern. The highest increases were for children under the age of 6, and for children in socially advantaged families (i.e. family income four or more times poverty level, and parents with college degree or higher).

DISCUSSION

The authors point out and discuss the limitations of their study. These include the fact that the disability data is broken down only by the 14 categories that have been used in the interview surveys. Secondly, the data is based on parent report rather than on direct observation of the children. Nevertheless, the procedures and categories used are essentially similar to those used since 1957, yet the trends noticed in the present survey represent a significant departure from previous experience.

So, to summarize: over the decade 2001-2011, the prevalence of parent-reported disability in children rose by 15.6%. But surprisingly, the greatest increases occurred among children in socially advantaged families, and in children under the age of 6.

Even more surprisingly, the incidence of disability due to physical conditions declined by 11.8%, while disability due to mental/neurodevelopmental conditions increased by 20.9%. And here again, the highest increases were among children under the age of 6, and children from more advantaged homes.

The authors suggest that at least some of the reason for these changes over time may be artifactual.

“There have also been changes in diagnostic labeling and thresholds: for example, a child formerly considered distractible may now be seen as diagnosable by parents, teachers, and health professionals.”

And:

“The increase in neurodevelopmental or mental health conditions was especially high among young children, a finding that may be attributed to increased awareness of these conditions and the need for a specific diagnosis to receive services such as early intervention.”

The authors suggest a number of reasons why disability in socially advantaged children is increasing faster than in other groups. These include: expanded use of diagnostic and treatment services; better access to care in advantaged families; greater acceptability of a mental health diagnosis among higher-income families; and diagnostic biases.

“Greater acceptance of mental health diagnoses by more advantaged parents, coupled with persistent diagnostic biases, may help explain the trends identified by this research.”

The authors call for additional research:

“Additional research is necessary to assess the impacts of changing diagnostic labels and thresholds, evolving cultural views of health and disability, variable access to health services, the contribution of provider biases, and the incentive for a diagnosis to receive services.”

Note particularly the phrase:

“…evolving cultural views of health and disability…”

The phrase is a little vague, but I believe it’s a reference to the fact that the proliferation of psychiatric diagnoses has had profound cultural and societal implications. Problems that previous generations considered eminently resolvable, through individual and collective effort, are now seen as disabling illnesses, that require professional intervention and drugs. Psychiatry isn’t just damaging its current clients, it is systematically laying the groundwork for future generations to think of themselves as damaged and powerless, and to seek psychiatric services.

It is particularly ironic that this process is accelerating to the degree shown in this study at a time when significant declines are being noted in reported physical disabilities. In the very decade that physical disabilities declined by almost 12%, neurodevelopmental/mental “disabilities” increased by almost 21%. In other words, although children are actually becoming less disabled, they are being given the message (and their parents are accepting the message) that they are more disabled.

At least part of the reason for this stems from the fact that while the prevalence of physical disability is limited by the prevalence of the particular pathology in question, no such limitation applies to “psychiatric disabilities.” Through the creative adjustment of criteria thresholds and the flagrant invention of new “illnesses,” psychiatrists can expand the scope of their practice, and consequent “disabilities,” more or less at will. And, as the expansion of the DSM across five editions demonstrates, they have not been shy in the pursuit of this endeavor.

There is truly no human problem that psychiatry can’t make ten times worse.