On May 16, 2014, the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry published an article by Deepa Archarya, PhD, et al. The article is titled Safety and utility of acute electroconvulsive therapy for agitation and aggression in dementia. Here are the authors’ conclusions:

“Electroconvulsive therapy may be a safe treatment option to reduce symptoms of agitation and aggression in patients with dementia whose behaviors are refractory to medication management.”

In their Introduction section, the authors write:

“Despite the high prevalence of these agitated and aggressive behaviors, there are currently no treatment options approved by US Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Nonpharmacological interventions, including environmental and behavioral modification, are difficult to implement in nursing home settings because of low staff-to-resident ratios.”

“Atypical antipsychotics have been found to be only modestly helpful in addressing behavioral symptoms and unfortunately are associated with dangerous side effects including tardive dyskinesia, cerebrovascular adverse events, sedation, and increased risk of mortality;”

“A major concern for using ECT in older patients, especially those with dementia, is its adverse effect on cognitive functioning. Research has found that most neurocognitive effects of ECT in older patients without dementia are short term and tend to resolve within a 6-month period.”

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Study participants were 23 individuals (mean age 73.8) who had been admitted to McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, or Pine Christian Mental Health Services, Grand Rapids, Michigan, with a diagnosis of dementia, and who had been referred for electric shock treatment for agitation and/or aggression. McLean Hospital is affiliated with Harvard Medical School, and Pine Rest with Michigan State University.

Patients were enrolled in the study after the authors “…obtained written informed consent from the AHCR [authorized healthcare representative] and assent from the study participants.” The term “assent” is widely used in the medical field to indicate that an individual, who is not legally competent to consent to a treatment, has indicated, verbally or non-verbally, a willingness to proceed.

Standardized agitation, neuropsychiatric, and depression inventories, as well as the Clinical Global Impression scale, were administered at approximately weekly intervals throughout the study period. The inventories were completed by nursing staff, and the CGI by the treating psychiatrist.

In addition, a Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE), Severe Impairment Battery (SIB), and an activities of daily living scale were administered at baseline (i.e. prior to the course of electric shocks) and at discharge. Though, because of “…agitation and/or inability to sustain attention” only 10 participants completed the before and after MMSE, and only 6 completed the SIB.

Electric shocks were administered three times per week “…or less frequently if clinically indicated.”

RESULTS

The mean number of electric shock sessions was 9.4, ranging from a low of 5 to a high of 14.

Participants’ scores improved significantly on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, and on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. “As needed” neuroleptic use declined from an average chlorpromazine equivalent dose of 7.8/week at the beginning of the study to 1.6/week at the end. But there was no change in the use of standing neuroleptic drugs. [“Standing” in this context means prescribed on a regular basis, through a standing order.]

Sixty-one percent of the participants (i.e. 14 of the 23) were using atypical antipsychotics on admission. This increased to 65% (i.e. 15 out of 23) by the time the shock treatment began, and had reverted to 61% at discharge.

There was no significant change in scores on the activities of daily living scale.

DISCUSSION

The authors write:

“Overall, our results demonstrated ECT to effectively reduce symptoms of agitation and aggression in older patients with dementia who did not respond to psychopharmacological intervention alone. This suggests that ECT may be a potential treatment option for patients with dementia who are refractory to medications for agitation and aggression. Importantly, there were significant reductions in behavioral disturbances by the third ECT session, and most participants showed a reduction in behavioral disturbances by the ninth ECT session. If borne out by subsequent trials, such rapid reduction in behavioral disturbances could have significant public health implications by improving the quality of life for patients with dementia, alleviating caregiver burden, and increasing residential placement options for patients.”

And:

“In our study, ECT was discontinued for two participants (both with end-stage dementia) because of poor response, which was defined by recurrence of agitation and aggression that reached approximately baseline severity levels. [Elsewhere in the report the authors state that one of these individuals died a month after his final ECT session, and that the treatment team determined that the cause of death was unrelated to the ECT.] Three participants, despite improvement in agitation and aggression, had adverse events that resulted in discontinuation of ECT.”

The authors point out that the study design was naturalistic, and lacked a control group.

COMMENT

The authors acknowledge that the study had a number of limitations, including the fact that it was “open label”. This means that the staff who rated the participants before and after the electric shocks were aware that the individuals had received these shocks. In fact, as is made clear in the text, the raters were involved in the care of the participants, and were probably invested in the outcome of the study. Under such circumstances, it’s very easy to see improvements and to ignore deteriorations in participants’ behavior. This is particularly the case in that the kinds of ratings used in a study of this nature necessarily involve a good measure of subjective judgment and interpretation.

The authors were aware of this concern, and they state:

“As this was the first naturalistic, prospective study of the use of ECT to treat agitation and aggressive symptoms in patients with dementia, the goal was to collect preliminary data for the development of a randomized, double-blinded, controlled clinical investigation.”

Nevertheless, the authors express considerable optimism for this “treatment”:

“Despite these limitations, our results are encouraging and suggest that ECT may be a rapidly acting, safe, and effective treatment for certain patients with dementia and behavioral disturbances that do not respond to or tolerate standard behavioral interventions and pharmacotherapy.”

Despite the caveats in the earlier part of this sentence, the optimistic tone strikes me as unwarranted by the study’s results.

The phrase “… patients with dementia and behavioral disturbances that do not respond to or tolerate standard behavioral interventions…” is also noteworthy, in that there is no mention in the study text that any kind of behavioral interventions had ever been attempted with the enrolled individuals, nor that a history of failure with these kinds of interventions was a pre-requisite for study enrollment. This is a critically important matter because the use of psychiatric interventions to “treat” agitation and aggression in cases of dementia is often criticized on the grounds that behavioral interventions are safer, more effective and should always be tried first. The authors’ implication that behavioral interventions had been tried without success seems misleading.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In Table 1 of the article it states that 65.2% (15 out of 23) of the individuals enrolled were recommended for “continuation ECT”. When we remember that five individuals were dropped from the study because of poor response or adverse events, it is clear that the effective percentage is 83% (15 out of 18). This is important in that there is a perception among the general public that electric shocks to the brain are a one-time “treatment” that somehow fix aberrant neural mechanisms. In reality, “continuation ECT” is very common. It is also, I think, noteworthy, that apart from the line in Table 1, there is no mention of continuation ECT in the text. It’s worth asking whether the medical proxies who signed the consent forms were aware that any gains from the “treatment” would be temporary, and that there was a high likelihood that electric shocks to the brain would become standard “treatment” for the individuals concerned.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

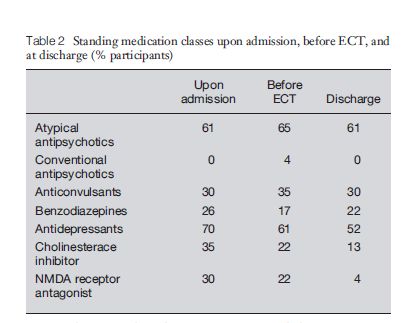

Many of the participants were taking psychoactive drugs on admission and on discharge. The authors provide the following table:

The admission percentages add up to 252, so it is clear that many of the participants were taking more than one of these drugs.

Several of these products have adverse effects that could readily contribute to agitation/aggression, and even to the dementia. Atypical antipsychotics, more accurately known as neuroleptics, for instance, cause tardive dyskinesia and akathisia, both of which are extraordinarily impairing and unpleasant. It is not difficult to accept that these drug-induced conditions could precipitate agitation and aggression, especially in people whose cognitive ability has declined. In fact, extreme agitation is the primary feature of akathisia.

An additional consideration here is that although, in their opening remarks, the authors draw attention to the lack of efficacy and dangerous side effects of antipsychotics in these situations, they continued to prescribe them for participants during this study.

Here are some known adverse effects of the other classes of drugs mentioned in the article:

Anticonvulsants: These drugs are used to treat epilepsy but are also used in psychiatry for the condition known as bipolar disorder. Lamictal (lamotrigine) is a member of this class. PDR.net lists confusion as a frequent adverse reaction; and akathisia, dyskinesia, hostility, memory decrease, and paranoid reaction as infrequent adverse reactions.

Benzodiazepines: These drugs are classed as sedatives/minor tranquilizers, and are widely used in geriatric populations. Librium (chlordiazepoxide) is a member of this class. PDR.net states that “Paradoxical reactions (e.g., excitement, stimulation, and acute rage) reported in psychiatric patients…” [Emphasis added]

Antidepressants: Even in psychiatric circles it has been acknowledged that these drugs can cause manic-like episodes. (DSM-IV: “Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder” p 332)

Cholinesterase inhibitors: These are commonly used as a treatment for Alzheimer’s dementia. Four cholinesterase inhibitors are approved by the FDA for this purpose: Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne, and Cognex. All four of these products (according to the NIH’s site MedlinePlus) have a wide range of unpleasant side effects, e.g., nausea, vomiting, incontinence, dizziness, blurred vision, muscle aches, headaches, extreme tiredness, stomach pain, uncontrollable shaking, etc., and it is certainly conceivable that individuals taking these drugs might become agitated or aggressive, especially individuals who, because of cognitive deficits, are unable to communicate their distress verbally. It is also noteworthy that aggressive behavior is mentioned by the NIH as a specific adverse effect of one of these products (Exelon)

NMDA receptor antagonists: This is a broad category of drugs, many of which induce a state known as dissociative anesthesia. Examples include: Ketamine, chloroform, alcohol. Ketamine is sometimes used in psychiatry for depression. Memantine, a member of this class, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, and probably accounts for most, if not all, of the NMDA/RA’s reported in this study. The NIH lists aggression as a specific side effect.

Given the extent to which these various drugs were being used by the study’s participants, it is certainly conceivable that the drugs were contributing to the agitation and aggression. The authors don’t appear to have considered this possibility, and in fact, state:

“It may be possible that the reduction in agitation and aggression may have been due to a synergistic effect between ECT and pharmacological treatment.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Against all this, it could be argued that the incidence of these various adverse effects is generally low, and couldn’t account for the frequency of aggressive behavior in the study participants. But the participants were not a random selection of people taking the drugs in question. Rather, they were individuals selected because of aggressive behavior, most of whom had been taking some or all of these drugs on admission. So it is a distinct possibility that the aggression was a drug effect for many, or even most, of the study participants.

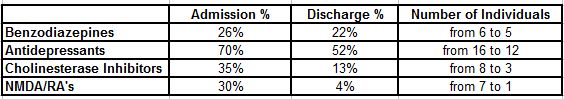

In addition, it is noteworthy that the use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants, cholesterinase inhibitors and NMDA/RA’s was discontinued towards the end of the study period for many of the 23 participants. From Table 2, reproduced above, we can calculate the number of individuals involved:

Given that all of these drugs have the potential to induce aggression/agitation, it is surely possible that discontinuing these drugs for some individuals could lower the overall incidence of these kinds of reactions.

So when Dr. Acharya, et al, state that: “It may be possible that the reduction in agitation and aggression may have been due to a synergistic effect between ECT and pharmacological treatment”, it is equally plausible that any reduction in the incidence of aggression is attributable to a combination of the state of docility often noted post-electric shock treatment plus the fact that aggression-inducing drugs were discontinued in many cases.

Unfortunately, what psychiatrists will likely take from the study is the self-serving conclusion that ECT is an acceptable way to manage agitation and aggression in people with dementia, and, unfortunately, this is also the message being given to the general public.

Sue Thoms is a journalist who writes for MLive/The Grand Rapids Press. On September 18, 2014, she wrote a piece for MLive. The article was apparently based on an interview with Louis Nykamp, MD, one of the study’s authors. Here are some quotes:

“Dementia patients who were severely agitated and aggressive benefitted from electroconvulsive therapy in a study conducted by researchers at Pine Rest Christian Mental Health Services and two other institutions.”

Note the unqualified assertion “…benefitted from…”, even though such a conclusion is not warranted by the study.

“Doctors don’t know how the ECT treatments work, he [Dr. Nykamp] added.

‘It’s possible that we are treating underlying agitated depression,’ he said. ‘Or it’s possible we are simply working through another mechanism to help modify some of the brain circuitry that is leading to the substantial agitation and impulsivity.'”

There it is: agitation may be caused by “underlying agitated depression”, the spurious superficiality of which notion is self-evident. Or: high voltage electric shocks delivered to the brain may fix aberrant brain circuits, a contingency which in any context other than psychiatric orthodoxy would be considered laughable. Electric shock treatment causes brain damage, and any putative gains claimed by psychiatrists are attributable to a well-known transient effect called post-concussional euphoria. Memory loss, in many cases, is more or less permanent.

It is, I suggest, a gross misuse of medical authority and medical credentials to subject older members of society to this kind of abuse.