On November 27, 2014, the Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society published a paper titled Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia. The paper was edited by Anne Cooke of Canterbury Christ Church University. The central theme of the paper is that the condition known as psychosis is better understood as a response to adverse life events rather than as a symptom of neurological pathology.

The paper was wide ranging and insightful, and, predictably, drew support from most of us on this side of the issue and criticism from psychiatry. Section 12 of the paper is headed “Medication” and under the subheading “Key Points”, you’ll find this quote:

“[Antipsychotic] drugs appear to have a general rather than a specific effect: there is little evidence that they are correcting an underlying biochemical abnormality.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

On the same date, The Mental Elf published a critique of the BPS paper. The Mental Elf is an Internet website that purports to offer “reliable mental health research, policy, and guidance.”

The critique of the BPS paper is presented in three parts. The first was written by Keith Laws, a psychologist, the second by Alex Langford, a trainee psychiatrist, and the third by Samei Huda, a consultant psychiatrist.

My purpose in writing this post is to address a paragraph in Dr. Langford’s essay.

“The ‘key point’ that there is ‘little evidence that [medications correct] an underlying abnormality’ is bizarrely unfounded. An excellent summary by Kapur & Howes (referenced earlier in the report itself) and further imaging studies by Howes and others provide solid evidence for elevated presynaptic dopamine levels being a key abnormality in psychosis, and there is copious evidence that inhibiting the action of this excess dopamine using antipsychotics leads to clinical improvement in psychosis.” [Emphasis added]

Note the term “bizarrely unfounded.” Not “questionable”; not “misleading”; not “false”; not “overstated”; not “open to discussion”; not “unlikely” – but “bizarrely unfounded”!

In support of this assertion, Dr. Langford cites Oliver Howes and Shitij Kapur’s The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: Version III—The Final Common Pathway, Schizophrenia Bulletin, March 2009, which he claims provides “solid evidence” that elevated presynaptic dopamine levels are a “key abnormality in psychosis.”

To help put Dr. Langford’s assertion in perspective, here are some quotes from the Howes and Kapur article, interspersed with my comments.

“The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia has been one of the most enduring ideas in psychiatry.”

The authors describe how the dopamine hypothesis, which, incidentally, has been around since the late 60’s, has gone through two major revisions. They refer to these as version I and version II. Then:

“Since version II, there have been over 6700 articles about dopamine and schizophrenia. We selectively review these data to provide an overview of the 5 critical streams of new evidence: neurochemical imaging studies, genetic evidence, findings on environmental risk factors, research into the extended phenotype, and animal studies.”

“It [The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia – Version III] explains how a complex array of pathological, positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other findings, such as frontotemporal structural and functional abnormalities and cognitive impairments, may converge neurochemically to cause psychosis through aberrant salience and lead to a diagnosis of schizophrenia.” [Emphasis added]

Note the word “may”, which suggests that the authors themselves did not regard the evidence as being quite as “solid” as Dr. Langford asserted.

“Although it is not possible to measure dopamine levels directly in humans, techniques have been developed that provide indirect indices of dopamine synthesis and release and putative synaptic dopamine levels.”

The fact that the primary variables cannot be directly measured, but rather are estimated from “indirect indices” suggests further that the evidence for version III may not be quite as solid as Dr. Langford asserts.

“Seven out of 9 studies in patients with schizophrenia using this technique have reported elevated presynaptic striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in schizophrenia, with effect sizes in these studies ranging from 0.63 to 1.89.”

“This, then, is the single most widely replicated brain dopaminergic abnormality in schizophrenia, and the evidence indicates the effect size is moderate to large.”

So essentially what’s being asserted here is that there is replicated evidence of abnormally high presynaptic dopamine production in the striatum area of the brain in people who carry a “diagnosis of schizophrenia.”

I don’t have the time to review all seven of the articles cited, but I did take a look at one: Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia, Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 (number 20 in the reference list). I chose this because the full text was readily available and because the principal author, Oliver Howes, MD, is also the principal author of the article cited by Dr. Langford.

Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, et al offer the following context for their study and report:

“A major limitation on the development of biomarkers and novel interventions for schizophrenia is that its pathogenesis is unknown. Although elevated striatal dopamine activity is thought to be fundamental to schizophrenia, it is unclear when this neurochemical abnormality develops in relation to the onset of illness and how this relates to the symptoms and neurocognitive impairment seen in individuals with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia..”

To address this question, they recruited three groups of people:

- 24 “patients having prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia,” recruited from a community mental health center;

- 7 “patients having schizophrenia” recruited from the same center;

- 12 “matched healthy control subjects” from the same geographic area.

All of these individuals received an intravenous injection of 150 MBq (megabecquerels) of 18 F-dopa 30 seconds after the start of PET imaging which lasted for 95 minutes. The neurochemistry of all this is extremely complicated, but the basic picture is this. Dopa is an amino acid that is produced from tyrosine in the liver. Through the action of the enzyme decarboxylase, it is converted in the brain to dopamine. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter, the overactivity of which is hypothesized as the cause of the condition known as schizophrenia.

As mentioned earlier, the accumulation or activity of dopamine in the brain cannot be measured directly. But one of the indirect measures of dopamine synthesis is the rate at which dopa is absorbed or taken up. When 18 F-dopa (a radioactive analogue of dopa) is used, the uptake can be observed and measured on a positron emission tomography (PET) brain scan. In these kinds of studies the rate of F-dopa uptake is normally expressed as a Ki value.

FINDINGS OF THE STUDY

As mentioned earlier, there were three groups of participants.

a) Twenty-four “patients having prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia”. The authors describe these individuals as having an “at-risk mental state (ARMS)”. The concept is similar to the APA “diagnosis” of “attenuated psychosis syndrome” (DSM-5, p 122)

b) Seven “patients having schizophrenia.” All seven reportedly met the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia.

c) Twelve “matched healthy control subjects” recruited from the same geographic area as the clinic. No information is provided as to how these individuals were recruited or screened.

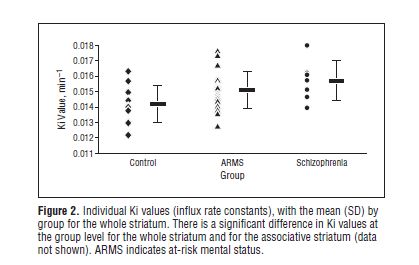

The results of the study are presented in Figure 2.

As can be seen, the diagram is divided into three vertical blocks: Control, ARMS, and Schizophrenia, reading from left to right. The Ki values are shown on the vertical scale on the left.

The black horizontal rectangle (▬) indicates the mean Ki value for each group. So the 12 controls had a mean of 0.0142; the ARMS group 0.0151; and the schizophrenia group 0.0157. On the face of it, this looks like an impressive result. The Ki values are steadily increasing across the three groups, strongly suggesting that dopamine synthesis capacity is increasing commensurately.

However, the individual scores in the three groups tell a somewhat different story. Each diamond indicates the score for a healthy control subject; the triangles give the scores for each ARMS participant; and the round dots give the scores for the participants “diagnosed with schizophrenia.” If we think of the healthy controls as having “normal” dopamine synthesis, then it is clear that Ki values between approximately 0.012 and 0.016 represent the normal range. And it is also clear that the only study participants with values outside the normal range were three from the ARMS group and one from the schizophrenia group. In other words, 87.5% (21 out of 24) of the ARMS participants, and 85.7% (6 out of 7) of the schizophrenia participants had Ki scores in the normal range.

The general point here is that mean values, although very useful and informative with some forms of data, can be quite misleading in other contexts. On the basis of the findings presented in this study, I don’t think one could reasonably infer that there is “solid evidence for elevated presynaptic dopamine levels being a key abnormality in psychosis”, as Dr. Langford asserts.

OTHER PROBLEMS WITH THE STUDY

Besides the marked overlapping of scores, there were other problems with the study. The first, and perhaps most obvious, is the problem of matched pairs.

In the paper’s abstract, the authors write:

“Twenty-four patients having prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia were compared with 7 patients having schizophrenia and with 12 matched healthy control subjects from the same community.”

This statement – particularly the word “matched” – conveys the impression that the “healthy control subjects” were similar to the members of the two focus groups in every respect except for those factors directly associated with a “diagnosis of schizophrenia” or “prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia”. This is the essential assumption underlying all matched pairs research, and is a reasonably robust assumption for studies in physical science, engineering, materials testing, and even, to some extent, in general medicine. In behavioral/psychological studies, however, the technique has serious limitations, because one would have to match on a dauntingly large number of variables to have even a remote chance that the two groups were sufficiently similar to enable one to draw even modest conclusions.

Here’s how it works in practice. A researcher recruits individuals for his study. The study might involve the administration of a treatment or, as in this case, observing something going on within the brain. Let’s say that 20 people have been recruited. The researcher then recruits 20 controls. The controls are people who don’t have the feature under consideration (in this case, “schizophrenia symptoms”) but who do match the recruited participants (individual for individual) on a number of variables that are considered relevant. So if the recruiter determines that age, gender, and education are the relevant factors, he would, for each participant, find a match: a person of the same age, same gender, and same education. So, if the experimental group responds to the treatment or yields different observations from those of the control group, one can have a measure of confidence in the validity of the results.

Most matched pairs studies provide a fairly detailed description of the matching process and the matching variables used. This is not provided in Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, et al. All we are told is that:

- the controls were recruited from the same geographic area

- the controls were “required to have no personal history of psychiatric illness”

- and that the “…groups were well matched for variables that might putatively alter dopaminergic systems such as substance use and age…”

The point of all this is that, even if we allow that dopamine synthesis was higher in the striatal area of the brain for the ARMS and schizophrenic groups than for the controls, it is unsafe to conclude that excessive dopamine synthesis is a neurological abnormality inherent to individuals who attract the labels ARMS and schizophrenia. It may be, for instance, that the dopamine difference is a reflection of some other factor entirely – something on which the controls and participants were not matched – e.g. a history of abuse or victimization or the experience of failure. And we certainly have no grounds for believing that the dopamine excess causes the loose collections of vaguely defined thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that psychiatrists label “schizophrenia” and “attenuated psychosis syndrome”.

This last point is important because it touches on the unreliability of psychiatric “diagnoses”. In studies of this sort, there is a tendency to accept the labels assigned to the different groups as 100% reliable. So all members of the ARMS group are considered to “have” attenuated psychosis syndrome; all members of the schizophrenia group “have” schizophrenia; and all members of the control group are considered to be “healthy” – i.e. having no psychiatric “illness”. In reality, psychiatric evaluations are unreliable. The kappa score for schizophrenia in the DSM-5 trials, for instance, was only 0.46. So if we were to take the 43 people involved in the present study and present them to say ten other psychiatrists in a variety of settings, we will almost certainly get different groupings. Some of the people in the focus groups will be considered “healthy” while conceivably some of those in the “healthy” group will be considered psychiatrically “ill”.

A further problem with the Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, et al study is the fact that one of the “patients” was taking quetiapine (100 mg/day) at the time of the study, and that others had apparently been taking neuroleptics in the past. All that the authors tell us is that:

“All patients were not taking antipsychotic treatment for at least 8 weeks, except for 1 patient with ARMS who was taking quetiapine fumarate (100 mg/d[omitted for 24 hours before imaging])”

It is known that neuroleptic drugs affect the dopamine system, and it is a reasonable assumption that none of the control subjects had ever taken these products. So we have another variable on which the groups were not matched. It seems unlikely that the neuroleptic-induced dopamine changes in the brain would have dissipated within eight weeks.

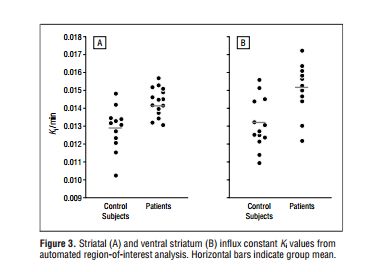

Lest it be thought that I cherry-picked the Howes et al study, here’s the comparable Ki graph from another study cited by Drs. Howes and Kapur. The study was conducted by Stephen McGowan et al (2004), Presynaptic Dopaminergic Dysfunction in Schizophrenia.

Here again, note that although the means differ in each analysis, there is a great deal of overlap when we look at individual scores. For the entire striatum (A), 11 out of 15 (73.3%) “patients” have Ki values in the same range as the controls. The corresponding Ki values for the ventral striatum (B) are 7 out of 11 (63.6%). So here we have another group of people “with schizophrenia”, 60-70% of whom have normal Ki values. In this study, incidentally, all the “patients” were taking neuroleptic drugs.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

To return to Dr. Langford’s original assertion:

“An excellent summary by Kapur & Howes (referenced earlier in the report itself) and further imaging studies by Howes and others provide solid evidence for elevated presynaptic dopamine levels being a key abnormality in psychosis, and there is copious evidence that inhibiting the action of this excess dopamine using antipsychotics leads to clinical improvement in psychosis.”

It is noteworthy that Drs. Kapur and Howes themselves were a good deal less certain:

“Two different kinds of evidence could lead to a complete rejection of the hypothesis. PET studies directly implicating presynaptic dopamine dysfunction are a major foundation of this new version of the hypothesis. PET data require to be modeled to provide estimates of L-dopa uptake or synaptic dopamine levels—and the results are inferred rather than direct measurements. Thus, if it turns out that the body of evidence based on PET imaging is a confound or an artifact of modeling and technical approaches, this would be a serious blow for version III, though the data behind versions I and II would still stand strong. While possible, we think this to be highly unlikely. What is perhaps more likely is that a new drug is found that treats psychosis without a direct effect on the dopamine system. In other words, the dopamine abnormalities continue unimpeded, and psychosis improves despite them. A good example of such a new drug might be LY2140023, an mGlu 2/3 agonist. If this were to be an effective antipsychotic and it could be shown that the new pathways do not show any interaction with the dopamine system, then the fundamental claim of version III, that it is the final common pathway, would be demolished. A similar situation would arise if a pathophysiological mechanism that does not impact on the dopamine system is found to be universal to schizophrenia. Much more likely is the possibility that the hypothesis will be revised but with a stronger version IV.” [Emphasis added]

So although Drs. Kapur and Howes express a general optimism for the hypothesis, they acknowledge that the theory could be demolished by future research. And:

“The next decade will provide more information on the role of dopamine, particularly how genetic and environmental factors combine to influence the common pathway, and better drugs will be developed that directly influence presynaptic dopaminergic function—both logical successors to the idea of a final common pathway.” [Emphasis added]

In the one Howes and Kapur reference that I reviewed (Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, et al 2009), the authors also express some cautionary notes:

“Results of recent clinical trials suggest that treatment with antipsychotic medication may reduce the severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms and the risk of schizophrenia in patients with ARMS. Our finding of dopaminergic overactivity in the ARMS group indicates why drugs that act on the dopamine system may have these effects. We conclude that presynaptic striatal dopamine function may be a promising target for future drug development in the treatment of psychotic disorders.” [Emphasis added]

AND INCIDENTALLY

The acknowledgement statement at the back of the Howes and Kapur article states:

“Howes has received investigator-led charitable research funds or speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. Kapur has received grant support or has been a consultant/scientific advisor or had speaking engagements with AstraZeneca, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD—Darmstadt, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen (Johnson and Johnson), Neuromolecular Inc, Pfizer, Otsuka, Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Servier, and Solvay Wyeth.”

The financial disclosure statement at the back of the Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, et al article states:

“Drs Howes, Montgomery, Murray, McGuire, and Grasby received investigator-led charitable research funds and honoraria from pharmaceutical companies manufacturing antipsychotic medication.”

ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE

The elevated dopamine synthesis hypothesis has been discussed by the British psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff (The Myth of the Chemical Cure, 2009). Here are three quotes:

“Another group of studies have measured the uptake of a radiolabelled dopamine precursor molecule, presumed to reflect the synthesis of dopamine in people with psychosis compared with healthy controls (Dao-Castellana et al. 1997; Elkashef et al. 2000; Hietala et al. 1995; Lindstrom et al. 1999; Reith et al. 1994). Results of these are inconsistent. Even the results of the ‘positive’ studies are incongruous with some finding increased uptake in the putamen but not the caudate nucleus (parts of the basal ganglia) (Hietala et al. 1995) and another finding increased uptake in the caudate but not the putamen (Reith et al. 1994). One study found no effect (Dao-Castellana et al. 1997) and the largest study so far found the opposite finding of reduced uptake in the ventral striatal area of the brain (Elkashef et al. 2000).” (p 93) [Emphasis added]

And:

“All recent studies were small, and although efforts were made to identify and include patients who had not previously taken neuroleptic drugs, known as ‘drug naïve’ patients, all but one of the studies also included patients who had taken these drugs in the past, often for long periods. Therefore prior treatment with drugs known to affect the dopamine system may be, at least partially, responsible for the findings.” (p 93)

And:

“However the biggest problem with all this research is the complete disregard for other possible explanations for increased dopamine activity. Dopamine release is known to be associated with numerous activities and situations that may differ between patients and healthy controls and may account for the difference in dopamine activity independent of the presence of psychosis. Motor activity and attention have been shown to increase dopamine activity and dopamine is involved in arousal (Berridge 2006). People with acute psychosis are likely to be more aroused and agitated than healthy controls and this may account for increased dopamine activity. None of the recent dopamine-psychosis studies have examined these possible confounders.” (p 93-94)

IN GENERAL

There is, in my experience, an unfortunate tendency among psychiatric practitioners to overstate their various chemical imbalance hypotheses, and to commensurately criticize, and even marginalize, those of us who offer alternative perspectives. Dr. Langford’s assertion is a good example of this, and his rejection of the BPS’s statement as “bizarrely unfounded” borders on incivility. There is nothing even remotely bizarre about the BPS statement, and, in fact, given the limitations of the studies cited, it is extremely well founded.

If psychiatry, at some time in the future, identifies a specific neurological abnormality, and demonstrates that this abnormality is present in all the people that they “diagnose with schizophrenia”, and in none of the people that are not so “diagnosed”, then they will indeed have established a key neurological abnormality associated with this condition. If, by further research, they establish that the causal sequence is from neurological abnormality to the problematic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of the individuals involved (as opposed, say, to the causality going the other way), then they will have uncovered something worth talking about. And if, by still further research, they show that the abnormality is pathological rather than, say, a variation of normal functioning, then they will indeed have established that the condition known as schizophrenia can properly be regarded as a neuropathological condition.

But such evidence is not currently to hand.