In 2010, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica published a study by Göran Isacsson et al. The paper was titled Antidepressant medication prevents suicide in depression. Here’s the conclusion:

“The finding that in-patient care for depression did not increase the probability of the detection of antidepressants in suicides is difficult to explain other than by the assumption that a substantial number of depressed individuals were saved from suicide by postdischarge treatment with antidepressant medication.”

It’s a complicated article, with some tenuous logic, but note in particular the contrast between the fairly cautious wording in the conclusion, and the bold, even brazen, assertion in the title.

But, in any event, it’s all moot, because the article was retracted by the authors and by Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica about sixteen months after publication. The retraction had been requested by the authors because of “…unintentional errors in the analysis of the data…”

The research in question was conducted in Sweden. Dr. Isacsson works at the Division of Psychiatry in the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. He has been writing since at least 1994 on the putative efficacy of antidepressants in the prevention of suicide.

The 2012 retraction notice did not attract as much attention as the original article, but it did stimulate a measure of discussion. Mickey Nardo wrote posts on the subject, here, here and here. Bob Fiddaman wrote a post here, and Ivan Oransky of Retraction Watch wrote on the matter here. Ivan reported that he had contacted Dr. Isacsson and Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica for more information, and received the following reply from Dr. Isacsson:

“We discovered lately that there was a coding error regarding diagnoses in the database we utilized for the 2010 paper. When corrected, antidepressants were detected in depressed suicides as often as could be expected and not less than expected which was the crucial finding in the paper. This means that no conclusion can be drawn from the study regarding antidepressants’ effects on suicide risk in any direction.

The database has not been used for other studies so no other papers are affected.”

Jan Larsson, a Swedish journalist, wrote an interesting article on the matter. Here’s an extended quote:

“Isacsson’s findings from 2010 were widely published in Swedish newspapers, with headlines like ‘Antidepressants prevent suicide’ (Dagens Nyheter), where it was said: ‘He [Isacsson] means that many become provoked to hear that depression is a deadly disease and that suicides can be prevented with medicines’. And, said Isacsson: ‘Therefore, it is important to show that antidepressants actually prevent suicide.’

In June 2012 I made an FOI request to Karolinska Institutet (where Isacsson is working) to get the corrected figures in this research project. I specifically wanted to get the document containing the correct percentage of antidepressants for those ‘who committed suicide and who had previously been treated at a psychiatric clinic for depression’ (the earlier mentioned group of 1077 persons).

The answer from Karolinska Institutet: This is confidential information, no data can be released.

It took a five month legal process to get access to the correct data. During this whole process Karolinska Institutet claimed that all the data in this research project were confidential.

In a final statement to the court, after having to answer specific questions, Karolinska Institutet stated that the correct figures did not exist at the time of the FOI-request – remember that they were said to be confidential at the time – but that the correct figures now had been produced.

Karolinska Institutet stated to the court: ‘that information has now been produced … The result shows that ‘the correct percentage’ is 56, meaning that of the persons who had been treated for depression in psychiatric care in the last five years before suicide, 56% had antidepressants in their blood when they committed suicide.’

So finally we got to know that the 15.2% in actual fact was 56% – an increase of 268% (from 164 persons to 603).

We had a seven pages long scientific article, with great impact in media, where doctors and the public got the message that antidepressants protect against suicide – an article built on Isacsson’s faulty finding that only 15.2% in the group had antidepressants in their blood when they committed suicide. And so the correct data, which completely defeated Isacsson’s speculations and conclusions in the original article, ‘published’ in a short statement to the court in Stockholm, where no doctor, no patient and no other researcher could find it.”

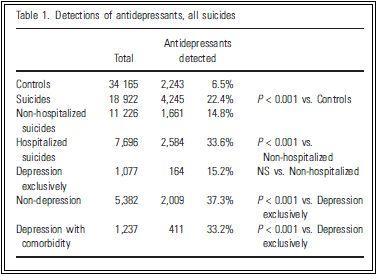

So, Dr. Isacsson et al’s original finding of 15.2% was a very large error indeed. As I mentioned earlier, the logic underlying the study is tenuous, but Table 1 from the study will provide some insight into the authors’ thinking.

The controls (34,165) are people who did not commit suicide. These are individuals who died from accidental and natural deaths. Antidepressants were detected in 6.5% of these individuals post-mortem.

The suicides (18,922) represent all Swedish suicides from 1992 to 2003. Antidepressants were detected in 22.4% of these people post-mortem.

Then the authors broke the numbers down further. They note that 11,226 of the suicides had no psychiatric hospitalization in the 5 years prior to their deaths. Of these individuals, 14.8% had antidepressants detected post-mortem. The remaining 7,696 suicides, who had been in a psychiatric hospital in the preceding 5 years, had an antidepressant detection rate of 33.6%.

And this is where it gets complicated. The researchers broke the hospitalized numbers down further, into:

- Those hospitalized for depression only 15.2%

- Those hospitalized for other problems 37.3%

- Those hospitalized for depression plus other problems 33.2%

Their argument was that the first group (depression only) would be expected to have about the same, or an even higher, level of detected antidepressants as the other groups. But, contrary to expectations, they found that they had the lowest level – about the same, in fact, as the group who had not been hospitalized in the previous five years.

So, they reason that large numbers of the hospitalized-for-depression-only group, most of whom presumably had antidepressants in their blood stream, had “been saved from committing suicide by antidepressant treatment.”

But as mentioned earlier, there was an error in the data, and the correct number was 56%.

Now all of this is well-known, but there is an aspect of the matter that has not, to my knowledge, been addressed previously. Let’s go back to Dr. Isacsson’s letter to Retraction Watch.

“We discovered lately that there was a coding error regarding diagnoses in the database we utilized for the 2010 paper. When corrected, antidepressants were detected in depressed suicides as often as could be expected and not less than expected which was the crucial finding in the paper. This means that no conclusion can be drawn from the study regarding antidepressants’ effects on suicide risk in any direction.

The database has not been used for other studies so no other papers are affected.”

Dr. Isacsson is saying that antidepressants were detected in the depression-only suicides “as often as could be expected and not less than expected.”

Strictly speaking this is true. 56% is not less than 15%. But the statement is also deceptive, in that 56% is a great deal more than 15%. The difference in the study in question is 439 people.

Dr. Isacsson issued the above statement on March 19, 2012. At that time, neither he nor Karolinska Institutet had released the 56% figure (on the patently spurious grounds of confidentiality). It took several more months of legal process before the 56% figure was produced. So at the time that Dr. Isacsson wrote “…not less than expected…”, he probably did not anticipate that the true figure would ever be released.

But the plot thickens even further:

“This means that no conclusion can be drawn from the study regarding antidepressants’ effects on suicide risk in any direction.” [Emphasis added]

If a particularly low number (15%) warrants the conclusion in the article’s title (“Antidepressants medication prevents suicide in depression”), wouldn’t it be reasonable to infer that a particularly high number (56%) might warrant the opposite conclusion? This is particularly so in that the increase from 15% to 56% can only have come at the expense of one or other of the remaining categories, which would make the discrepancy even larger.

I’m perfectly willing to accept that the original analysis was a genuine error. But at the time of the retraction and the letter to Retraction Watch, Dr. Isacsson must have known that the true figure was 56%, and the question needs to be asked: Why did he not release the 56% figure voluntarily at the time of discovery? In addition, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that his letter to Ivan Oransky was deliberately deceptive. Mickey Nardo puts the matter well:

“It would be easy to drift into a debate about the relationship between suicide and antidepressants and miss the point here, which is that medical opinion should follow science, not the other way around. It’s clear that Göran Isacsson is of the opinion that antidepressants should be given to decrease the incidence of suicide – he has an absolute right to express that opinion. But when Isacsson offers as proof of his opinion a published study of the Swedish public records, and it turns out that his data either is wrong, not to be found, or never existed in the first place, we have to conclude that Göran Isacsson is an ideologue and has no place in the psychiatric literature.”

At the time of writing the article in question, Dr. Isacsson had financial ties to Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, and GSK.

INCIDENTALLY

Dr. Isacsson not only continues to promote the notion that wider use of antidepressant drugs will prevent suicides, but he also calls routinely for the removal of the FDA’s black box warning on this matter (e.g. here).

In June 2010, the British Journal of Psychiatry published a debate on the topic: The increased use of antidepressants has contributed to the worldwide reduction in suicide rates. Arguing for the notion were Dr. Isacsson and Charles L. Rich, MD, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry, University of South Alabama; arguing against were Jon Jureidini, MD, child psychiatrist at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, and Melissa Raven, PhD, Research Fellow at Flinders University. Adelaide.

The debate effectively discredits Dr. Isacsson’s position, and is well worth reading.