On March 25 of this year, Psychiatric Times published an article titled Dementia, Agitation, and Aggression: The Role of Electroconvulsive Therapy. The author is Manjola Ujkaj, MD PhD, and the article’s subtitle is “What role might electroconvulsive therapy play for short-term treatment of agitation and aggression in patients with dementia?”

According to their website Psychiatric Times is a medical trade publication that covers news, reports, and clinical content related to psychiatry “for psychiatrists and allied mental health professionals who treat mental disorders.” The circulation of the monthly print publication is approximately 40,000.

Dr. Ujkaj is a psychiatry instructor at Harvard.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dr. Ujkaj begins by outlining the scope of the problem:

“Agitation and aggression are some of the most frequent and disruptive neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia. Approximately 45% to 80% of patients with dementia will exhibit agitation and aggression, depending on the clinical setting and dementia stage. Agitation and aggression have a major negative impact on disease burden, with higher incidence of functional decline and loss of independence, more frequent hospitalizations and premature institutionalization, higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and higher degree of caregiver stress and burnout.”

and

“Although agitation and aggression are among the most significant challenges in current dementia care, their treatment continues to be suboptimal. Currently there are no FDA-approved treatments for this indication.”

Dr. Ujkaj points out that behavioral interventions “… are considered to be the first-line treatment approach”, but that “… their use in everyday clinical practice is limited by multiple factors, most commonly lack of adequate training, time, and other resources.”

This is a routine claim in psychiatric literature, but the underlying question is seldom addressed: if, in the care of our senior citizens, we can afford enormous sums of money for psychiatric consultations, expensive name brand drugs, and electric shock machines, why can’t we afford to hire some behavior analysts and trainers?

Dr. Ujkaj expresses concerns about the use of pharmacological agents to control aggression.

“Psychotropics should be considered only in cases in which agitation and aggression pose a serious acute threat to the safety of the individual or that of others. Nonetheless, in clinical practice, off-label use of psychopharmacological agents for agitation and aggression—including antidepressants (sertraline), antiepileptics (carbamazepine), cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil), memantine, benzodiazepines (lorazepam), typical (haloperidol) and atypical (risperidone) antipsychotics (the antipsychotics are frequently used)—predominates over nonpharmacological interventions. However, most of these agents provide limited and short-lived efficacy, and there are serious concerns about adverse effects.”

All of which sets the stage for:

“ECT as a treatment option”

Dr. Ujkaj tells us that

“The use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for short-term treatment of agitation and aggression has limited evidence consisting of 9 retrospective case reports and series and only 1 prospective study. Most of the case reports and series describe the successful use of ECT for treatment of agitation and aggression without previous mood or psychotic disorders. In all of these cases, ECT was well tolerated, with no persistent cognitive impairment. Prolonged yet transitory postictal confusion developed in only 2 patients. ECT was found to be safe and efficacious for agitation and aggression comorbid with mood disorders in patients with dementia.

Findings from a recent open-label study indicate that acute ECT significantly decreased agitated and aggressive behavior by the third session. Moreover, most of the 23 participants showed a more significant reduction by the ninth session. Treatment was discontinued in 2 participants because of the lack of efficacy and in another 2 participants because of delirium. In a patient in whom atrial fibrillation developed, treatment was safely continued after transfer to a general medical hospital for ongoing cardiac monitoring.”

Which sounds pretty convincing. But – skeptic that I am – I decided to take a closer look at the references that Dr. Ujkaj cites in support of this conclusion. In her paper, these are references 9-18.

- Holmberg SK, Tariot PN, Challapalli R. Efficacy of ECT for agitation in dementia: a case report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;4:330-334. This paper is a case study on one individual.

- Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP, Burke WJ. ECT for screaming in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8:177. This is a letter to the editor, and describes a single case study.

- Aksay SS, Hausner L, Frölich L, Sartorius A. Severe agitation in severe early-onset Alzheimer’s disease resolves with ECT. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:2147-2151. This is a case report involving one 57-year-old client.

- Grant JE, Mohan SN. Treatment of agitation and aggression in four demented patients using ECT. J ECT. 2001;17:205-209. This paper describes four case studies.

- Bang J, Price D, Prentice G, Campbell J. ECT treatment for two cases of dementia-related pathological yelling. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20:379-380. This is a letter to the editor that describes two case studies.

- Wu Q, Prentice G, Campbell JJ. ECT treatment for two cases of dementia-related aggressive behavior. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:E10-E11. This is also a letter to the editor: two case studies.

- Ujkaj M, Davidoff DA, Seiner SJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy for the treatment of agitation and aggression in patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:61-72. This is a “retrospective systematic chart review” of 16 clients.

- McDonald WM, Thompson TR. Treatment of mania in dementia with electroconvulsive therapy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35:72-82. This paper presents case studies on 3 individuals.

- Sutor B, Rasmussen KG. Electroconvulsive therapy for agitation in Alzheimer disease: a case series. J ECT. 2008;24:239-241. This is a chart review study of 11 clients.

- Acharya D, Harper DG, Achtyes ED, et al. Safety and utility of acute electroconvulsive therapy for agitation and aggression in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;30:265-273. This is an open-label study of 23 participants. I have done a detailed critique of this study in an earlier post.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

So to put matters in perspective, Dr. Ujkaj’s assertions that

“ECT was well tolerated with no persistent cognitive impairment”

and

“ECT was found to be safe and efficacious for agitation and aggression comorbid with mood disorders in patients with dementia”

are based on 18 published papers, most of which were case studies, none of which were randomized controlled trials, and together involved a grand total of 64 participants.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I don’t have the time or the space to critique all of these papers, so I picked one at random. It’s reference number 11 in the list above: Severe agitation in severe early-onset Alzheimer’s disease resolves with ECT, by Aksay SS, et al. Correspondence author is Alexander Sartorius, Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Below are some quotes from the paper interspersed with my comments.

“The patient was a 57-year-old, right-handed woman with a 4-year history of rapid progressive dementia of Alzheimer type…Her psychiatric history included two depressive episodes 26 and 18 years previous, following critical life events, which remitted in the course of months without specific therapy. She was admitted to our clinic for evaluation and treatment of severe behavior disturbances, including severe restlessness, yelling, crying, refusal to eat and drink, physical aggression, and resisting care, which made further caretaking of the patient at home by family members impossible.”

“Her medication on admission included the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine patch (9.5 mg/d) and antipsychotic agent quetiapine (50 mg/d).”

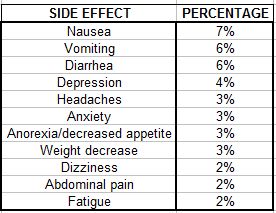

Rivastigmine is used to treat mild to moderate dementia, which is presumably why it was being prescribed in this case. It has some potentially serious adverse effects. These are listed below for the 9.5 mg patch with the percentages of people who experience each. (Source: PDR)

These are fairly large percentages, and it is entirely possible that the individual was experiencing abdominal pain to which she was unable to alert her caregivers. The authors tell us that verbal communication “…was substantially hindered by impairment of language comprehension.”

There is no information in the paper as to why quetiapine (a second generation neuroleptic) was being used. Perhaps this was a pre-admission attempt to “treat” the agitation.

“Her agitation symptoms proved unresponsive to combined behavioral therapy. Multiple trials of various psychopharmacologic agents were also ineffective: no improvement could be observed with quetiapine at increased doses (up to 175 mg/d), risperidone (up to 2.5 mg/d), melperone (up to 100 mg/d), and pipamperone (up to 80 mg/d). In due consideration of depressive episodes in her medical history, we started an antidepressive combination therapy with sertraline (200 mg/d) and mirtazapine (30 mg/d), which induced an improvement of sleep but no decrease in agitated behavior. Treatment with lorazepam (up to 4 mg/d) brought about a temporary affective loosening, which lasted only 4 days.”

The authors provide no details concerning the “combined behavioral therapy”.

It is noteworthy that so many psychiatric drugs were administered, all of which have potential side effects that involve pain/discomfort, including: headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, blurred vision, etc… In fact, most of the products mentioned can cause agitation!

“After 9 weeks in our hospital, ECT was initiated. At this time, the patient was receiving rivastigmine (9.5 mg/d), sertraline (200 mg/d), and mirtazapine (30 mg/d). Due to her inability to give informed consent, her daughters – who were also her legal guardians – agreed to the treatment, after detailed information and discussion.”

“A marked difference in the clinical presentation of the patient was noted after just two ECT treatments: the patient was noticeably less agitated, and crying occurred only for short episodes. Her improvement continued throughout the entire course of eight treatments given over 26 days. She stopped yelling and crying, showed no aggression, smiled spontaneously, and was more redirectable. The patient continued to pace, but she was able to sit and lay down for longer periods.”

Many individuals become more peaceful and apathetic after ECT. This observation is presented, in psychiatric circles, as evidence that the “treatment” works. But there is a growing recognition that it is more accurately characterized as post-concussional euphoria, a common, and usually short-lived, consequence of severe concussion.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“The ECT treatment was tolerated well, with signs of headache after the first three sessions. In the third week of treatment, a single self-limiting, spontaneous generalized seizure was observed.”

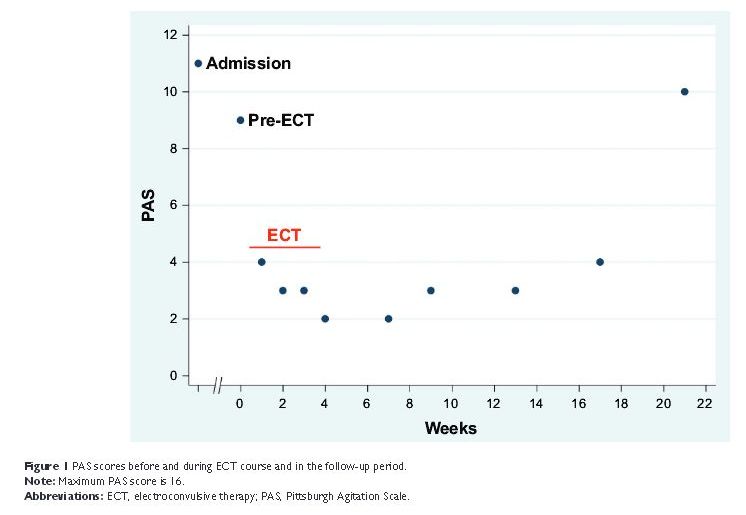

“The patient was discharged 5 days after the last ECT treatment. The improvement in agitation symptoms was present on hospital discharge. The guardians refused maintenance ECT since the patient moved away from our clinic to be taken care of by other family members. Katamnestic [follow-up] data on clinical presentation and behavioral symptoms of the patient were collected, by caregiver interviews, every 2 weeks over a period of 4 months after hospital discharge. Based on this information, PAS [Pittsburgh Agitation Scale] scores were determined. The improvement of agitation symptoms initiated by ECT lasted for approximately 12 weeks without any additional therapy other than rivastigmine, sertraline, and mirtazapine (Figure 1). In the follow-up period, two further self-limiting, spontaneous generalized seizures were reported.”

Note that about four months after the electric shock treatment, the agitation and aggression had returned to pre-shock treatment levels. It is also noteworthy that the family caregivers chose not to continue with the electric shock treatment.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“The etiology of behavioral disturbances in dementia is poorly understood. Abnormalities of neurotransmission (eg, gamma aminobutyric acid [GABA]ergic and dopaminergic dysfunction, cholinergic and serotonergic deficiency, and noradrenergic hyperactivity) have been implicated to play a role in behavior modulation, promoting agitation and aggression. It has been previously postulated that ECT may mediate its beneficial effects through its known enhancement of GABAergic transmission and inhibition.”

Or it may be that the agitation stems from some discomfort or pain that the individual is unable to communicate – such as abdominal pain from ingesting rivastigmine, or akathisia from ingesting quetiapine, or any of the other adverse effects listed above (including withdrawal effects). Or perhaps the critical factor was simple human frustration stemming from the fact that the woman was unable to communicate her concerns and needs!

“The occurrence of spontaneous seizures was considered to be a result of extensive neurodegeneration in the course of Alzheimer’s disease and not an adverse effect of the treatment since ECT is known to have considerable anticonvulsant effects and not to cause epilepsy.”

In support of the latter statement, the authors cite a paper by Ray AK: Does electroconvulsive therapy cause epilepsy? In this article, Dr. Ray describes a study completed at the Central Institute of Psychiatry, India. The study was a retrospective chart review of 619 individuals, and the author reported:

“No case of tardive seizure or spontaneous seizure was found after ECT among the study group of patients during hospitalization and follow-up.”

But Dr. Ray also acknowledges that his study had some significant limitations:

“In the limitations, our study design being a retrospective chart review, technically, there remains some chance of information being not reported during follow-up. Even the responses of postal communications were meager: 6.1%.” [Emphasis added]

So Dr. Ray has no information whatsoever on whether the other 93.9% of the study’s participants became epileptic. It is truly telling that the only reference that Dr. Aksay et al could adduce to support the notion that ECT does not cause epilepsy is a study with such profound limitations.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“The concern of greater long-term cognitive adverse effects of ECT in patients with severe dementia is not supported by any evidence so far, considering that in most of the reported cases, patients suffering from behavioral disturbances were in the last stage of dementia.”

What’s being said here, essentially, is that the cognitive ability of the individuals concerned is so poor that it would not be possible to discern any deterioration even if it had occurred.

This general theme is echoed in one of the other references in the Ujkaj paper.

- ECT for screaming in dementia, Roccaforte et al.

“Why ECT was effective is unknown. Screaming may be a behavioral ‘equivalent’ of a psychiatric syndrome responsive to ECT, such as depression, mania, or catatonia. Another possibility could be related to findings in patients with dementia that show a tendency for behavioral problems to spontaneously diminish in more advanced states. ECT may temporarily ‘shift’ a patient to a ‘later stage,’ thus advancing them quickly past the point of behavioral dyscontrol.”

“Shifting” a patient to a “later stage” sounds awfully like causing damage, and accelerating the individual’s decline and, presumably, death. Also note the truly perfect example of psychiatric “logic” in the first part of the above quote: ECT “works” for depression, mania, and catatonia, so, since ECT suppresses screaming, maybe screaming is the “equivalent” of depression, mania, or catatonia. Analogously: hammers work well on nails; but they can also be used to crack walnuts; therefore, walnuts are equivalent to nails!

SOME GENERAL POINTS

Several of the papers provide a list of the drugs that the individuals were taking on admission. For instance: (psychiatric drugs are shown in red)

13. Bang J et al:

Case 1:

“Two months prior to admission she was treated with risperidone and then quetiapine with no improvement. A trial of escitalopram was ineffective. Subsequent trials of olanzapine and divalproex were similarly ineffective.

Her medications on admission included those previously mentioned as well as spironolactone, ranitidine, oxycodone, lorazepam, memantine, and carbidopa/ L -dopa (sinemet).”

Case 2:

“Trials of haloperidol and thioridazine were ineffective. When her verbal agitation escalated to the point of disrupting the group home environment, she was referred for admission.”

“Her medications upon admission included ranitidine, levothyroxine, sertraline, and thioridazine.”

14. Qun Wu, et al.

Case 1:

“Therapeutic trials of sertraline, risperidone, olanzapine, intramuscular haloperidol, and valproate at the nursing home were ineffective.

His medications on admission included satolol, metformin, acetaminophen, trazodone, oxycodone, memantine, levothyroxine, tamsulosin, donepezil, allopurinol, simvastatin, and lisinopril.”

Case 2.

“Trials of trazodone, quetiapine, sertraline, and topical lorazepam at his nursing home were ineffective or poorly tolerated.

His medications on admission included sertraline, pramipexole, thiamine, simvastatin, and acetaminophen. Memantine and donepezil were discontinued prior to admission due to poor tolerance.”

It seems clear that psychiatric drugs are used fairly liberally in these situations, and as mentioned earlier, it is entirely possible – given the adverse effects of these drugs – that this practice is exacerbating the agitation/aggression problem.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

All of the papers expressed a measure of optimism regarding the safety and efficacy of electric shocks in reducing agitation and aggression. For instance:

#10. “In conclusion, a small number of case reports indicate that ECT is a potentially helpful treatment for dementia patients with distressing screaming that does not respond to less invasive interventions.”

#11. “Our case demonstrates that ECT can be safely and effectively used in treating pharmacotherapy-resistant severe agitation in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in its last stage, without any recognizable worsening of cognitive functions.”

#12. “We suggest that ECT is beneficial in these potentially life-threatening behavioral disturbances.”

#13. “ECT is rarely considered as an intervention for severe, refractory behavioral dyscontrol in patients with dementia though its use is considered safe, with fewer potential side effects, and more cost-effective than psychopharmacology alone.”

#14. “…a growing literature identifies ECT as an effective intervention for severe refractory agitation and aggression for patients with dementia.”

#15. “These results suggest that ECT is an effective and safe treatment for agitation and aggression in dementia. Further prospective studies are warranted.”

#16. “We conclude that a short course of ECT, followed by maintenance treatments every 2 weeks, can contribute significantly to the management of dementia patients whose behavioral agitation is associated with signs of mania.”

#17. “Electroconvulsive therapy is a safe and effective treatment for agitation in AD patients.”

Several of the papers mention a need for further study, and two papers call for randomized controlled trials to assess safety and efficacy. The two papers are references number 11 (2014) and 14 (2010). As of this date, no RCT’s have been conducted. Nevertheless, the “treatment ” is clearly being promoted as safe and effective, based on “growing evidence” of the sort set out here.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

EARLY INTRODUCTION OF ECT AS A TREATMENT

Dr. Ujkaj recommends that ECT’s “…availability as an off-label treatment option should be presented early during treatment planning.”

“Providing adequate, comprehensive, and timely information about possible risks and benefits associated with this specific ECT indication will allow the patient, family, and the authorized health care representative to achieve an optimal informed decision.”

But this is misleading, because adequate and comprehensive information about risks and benefits in this context is not available, and will not be available, until double-blinded randomized controlled trials have been undertaken. It is not known, for instance, if routine ECT reduces life expectancy in this context. And, if it does reduce life expectancy, it is not known by how much.

On the subject of informed consent, Dr. Ujkaj writes:

“A possible challenge is the continued refusal on the patient’s side to provide general assent despite ongoing efforts to identify and/or adequately address the reasons for refusal. In such a case, only a court order can allow ECT treatment to proceed.”

which has an ominous ring.

MAINTENANCE ECT

It is often not appreciated by the individuals receiving electrically induced convulsions that any gains they receive from the procedure will almost certainly be short-lived, and that the “treatment” will need to be repeated more or less indefinitely at intervals of about a month. Dr. Ujkaj mentions maintenance ECT in her Psychiatric Times article, and most of the references also mention this requirement. Interestingly, one of Dr. Ujkaj’s criticisms of the use of drugs in these situations is that they “…provide limited and short-lived efficacy.” [Emphasis added] But she does not direct this criticism at ECT.

SUMMARY

There is some prima facie evidence that some individuals with dementia who have been displaying agitation and aggression, and are subjected to electric shock “treatment” seven or eight times over a two week period, become more docile and compliant. This docility lasts for about two or three weeks (sometimes a little longer), at which point they need more electric shocks, presumably for the rest of their lives. The effect of this “treatment” on life expectancy for these individuals has not been formally studied.

DISCUSSION

Perhaps the biggest problem with Dr. Ujkaj’s paper, and the various studies that she cites, is that they convey the impression that the matter is being researched, when, in fact, it isn’t. Case studies can be helpful and informative, but they tell us little or nothing on the general questions of safety and efficacy. For instance, a case study that reports a successful outcome tells us nothing about other case studies that might have had unsuccessful – or even disastrous – outcomes. In addition, little credibility can be attached to the assessments of practitioners who themselves administered the “treatment”, and who have a vested interest in the outcome.

It is for precisely these kinds of reasons that the double-blinded, randomized controlled trial has been developed.

And besides, there is a growing body of solid evidence that electrically induced convulsions cause brain damage. It seems unlikely that elderly people with dementia would somehow be immune to these effects.

A second problem with Dr. Ujkaj’s paper is that it presents the matter as if it were a medical issue, when in fact it is an ethical/legal issue. The fundamental point here is that electrically-induced convulsions do not treat agitation and aggression in the medical sense of the term. Rather they suppress agitation and aggression, and probably inflict damage in the process. And the fundamental question is whether or not this is an appropriate and proper thing to do. But this is not a medical question. It is an ethical/legal question on the use of restraints. Medical research might throw some light on various facets of the matter, but ultimately the question needs to be shifted from the medical arena into the political/legal/civil rights arena.

People with dementia are still people, and they don’t surrender their human rights at the door of a mental hospital. Throughout its modern history, psychiatry has abrogated these rights under the guise of providing necessary treatment for illness. Restraints and confinement have been used with little more oversight than a psychiatrist’s signature. When courts are involved, their contribution is usually a rubber-stamp endorsement of the psychiatrist’s decisions.

The critical need at this juncture is, I suggest, to recognize that the use of shock-induced convulsions to suppress agitation and aggression in people with dementia is not a medical treatment, but is rather a form of short-lived, and probably damaging, restraint.

Meanwhile, the “safe and efficacious” mantra which appears in almost all the papers mentioned earlier is a poor substitute for truthful and open dialogue, and is no substitute for appropriate protection of the civil rights of this, most vulnerable, group.