In November of last year, the Schizophrenia Bulletin published online a research study: Antipsychotic Treatment and Mortality in Schizophrenia, by Minna Torniainen et al. The research was conducted in Sweden.

The authors offer the following background for the study:

“It is generally believed that long-term use of antipsychotics increases mortality and, especially, the risk of cardiovascular death. However, there are no solid data to substantiate this view.”

and the following conclusions:

“Among patients with schizophrenia, the cumulative antipsychotic exposure displays a U-shaped curve for overall mortality, revealing the highest risk of death among those patients with no antipsychotic use. These results indicate that both excess overall and cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia is attributable to other factors than antipsychotic treatment when used in adequate dosages.”

On the face of it, this finding would seem to upset the notion, widely accepted in antipsychiatry circles, that neuroleptic drugs are toxic, and that their use, especially prolonged use, markedly reduces life expectancy. There are, however, some problems with the study that need to be considered.

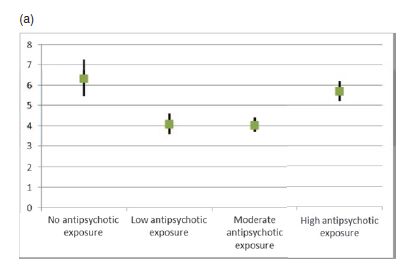

First, let’s take a look at one of the graphs presented in the article.

Fig. 1. (a) Overall mortality as hazard ratios in the chronic patient population (N = 21 492) compared with mortality in the control sample.

What we see graphed here are the mortality figures for the four groups identified and followed in the study.

- participants with no exposure to neuroleptic drugs

- those with low exposure

- those with moderate exposure

- those with high exposure

Mortality is presented as a hazard ratio compared to matched pairs in a control sample.

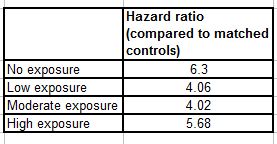

The actual numbers are:

So the individuals with no neuroleptic exposure had 6.3 times the death rate as their matched controls. The low exposure group, 4.06, and so on.

The black vertical lines through each graph value represent the 95% confidence interval for that value. What this means is that we can be 95% confident that the true value of each hazard ratio lies within the range of the vertical black line. Note that the confidence interval is widest for the zero use group. This is because they were numerically the smallest group.

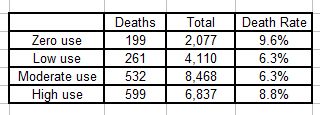

The numbers of people who died in each group were:

Total sample size was 21,492, and the results appear to confirm the authors’ conclusions: that the mortality rates for people “diagnosed with schizophrenia” bear a U-shaped relationship to neuroleptic use, with the highest rates associated with both zero and high use.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Note that two comparisons were made. Firstly, all the individuals labeled schizophrenic were compared to the “control sample”, and secondly within the “schizophrenia” group comparisons were made between the four sub-groups: zero, low, moderate, and high users of neuroleptic drugs.

For comparative research of this sort to be valid, there is a fundamental requirement that the target group has to be essentially similar to the comparison group in every respect, except the characteristic under study, which in this case is, firstly, the presence of a “diagnosis of schizophrenia,” and secondly, the degree of neuroleptic exposure.

The importance of this assumption can be readily appreciated by an example. Suppose that all the members of the zero-neuroleptics group in this study had a history of heart problems, and none of those taking the drugs had such problems. Clearly, the conclusion would be flawed because a group of people with heart problems will, other things being equal, have a higher mortality rate than people without such problems.

It is to counter such problems that researchers use double-blinded randomized controlled trials (DBRCT’s). In a DBRCT, study participants are recruited, and are randomly assigned to receive either a treatment or a placebo. The treatment provider, the client, and the person who is rating the outcome are “blinded” – i.e. they don’t know which participants have received the treatment and which have received the placebo.

The randomization process allows us to be reasonably, but not totally, certain that the two groups are sufficiently similar to allow comparisons to be made.

The study under consideration here was not a DBRCT. It was an observational, matched pairs study. Here’s how the authors describe their methods:

“We identified all individuals in Sweden with schizophrenia diagnoses before year 2006 (N = 21 492), aged 17–65 years, and persons with first-episode schizophrenia during the follow-up 2006–2010 (N = 1230). Patient information was prospectively collected through nationwide registers. Total and cause-specific mortalities were calculated as a function of cumulative antipsychotic exposure from January 2006 to December 2010.”

The study is observational in that the authors simply identified all individuals in Sweden with “schizophrenia diagnoses” prior to 2006 and individuals who had a first-episode of psychosis and a “diagnosis of schizophrenia” between 2006 and 2010. They then searched death registers and drug prescription registers to observe and document mortality rates for zero, low, moderate, and high users of neuroleptic drugs.

As mentioned earlier, the study entailed two different comparisons – mortality rates for individuals labeled “with schizophrenia” were compared to rates for the control sample; and within the “schizophrenia” groups mortality rates were compared for zero, low, moderate, and high neuroleptic users.

The control groups for the first comparison consisted of “…age- and gender-matched controls from the general population…”

“The mortality in persons with schizophrenia was compared with a control sample from the general population. For each person with schizophrenia, we identified 10 age- and sex-matched persons without schizophrenia.”

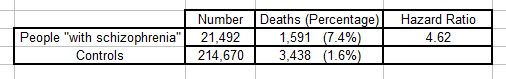

The results for the first comparison were:

The authors don’t tell us exactly how the matched controls were selected. All we know is that for each member of the “schizophrenia” group there were ten controls of the same age and gender who did not “have schizophrenia”. This was a total of 214,670 individuals.

There are two problems with this approach. Firstly, no amount of matching of this sort can produce truly comparable groups. The reader has only to bring to mind people of the same age and gender as him/herself to realize that the differences will outweigh the similarities. Using ten controls for each study participant does improve the situation somewhat, in that the resulting averaging will tend to smooth out extreme differences, but the problem is by no means eliminated.

Secondly, “schizophrenia” is a notoriously unreliable label. The DSM-5 trials yielded Kappa scores of only 0.46. What this means essentially is that, of the 21,492 participants labeled as “having schizophrenia”, a substantial number would not be so labeled if examined by an independent psychiatrist.

Matched-pairs studies can be useful in general medicine, where the number and the nature of confounding variables are often relatively limited. But they are problematic in psychological/behavioral research because of the inherent complexity of the subject matter and the almost infinite range of potential confounders.

MORTALITY RATES AND NEUROLEPTIC USE

As mentioned earlier, the graph and the hazard ratios would appear to confirm the authors’ conclusion that the zero-users had the highest mortality rate. However, there are a number of observations that need to be made.

1. There is normally a great deal of pressure on people who receive “a diagnosis of schizophrenia” to take neuroleptic drugs. From the numbers presented in the study, 2077 of the 21,492 participants took no neuroleptics. So, either the treating psychiatrists did not prescribe the drugs, or the individuals refused to take them. In either event, I think it is clear that these individuals, taken as a group, are dissimilar from those individuals who did take the drugs. In the absence of more detailed information about these individuals, it is not safe to attribute their excess mortality to the fact that they didn’t take the neuroleptics. Indeed, the authors acknowledge this:

“Because the nature of this study is observational, the associations may not necessarily mean causality. The results concerning comparative mortality between different exposure groups did not change substantially when the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics were controlled in the secondary analysis within the patient population. However, it is not possible to fully adjust for the severity of the illness and lifestyle characteristics by using such databases, which do not include information on smoking or diet, for example. Disease may be more severe in patients with high medication use than in patients with moderate antipsychotic use, and therefore the higher mortality in this group may partially derive from disease severity.”

But, by exactly the same token, some unidentified extraneous factor may be at work within the zero-use group and may account for their higher mortality rate.

2. The zero-use individuals may not have been truly zero-use.

“…because antipsychotic medications that may be used in hospitals are not recorded in the Prescribed Drug Register.”

“…no information was available on the use of medication during the hospital treatment days…”

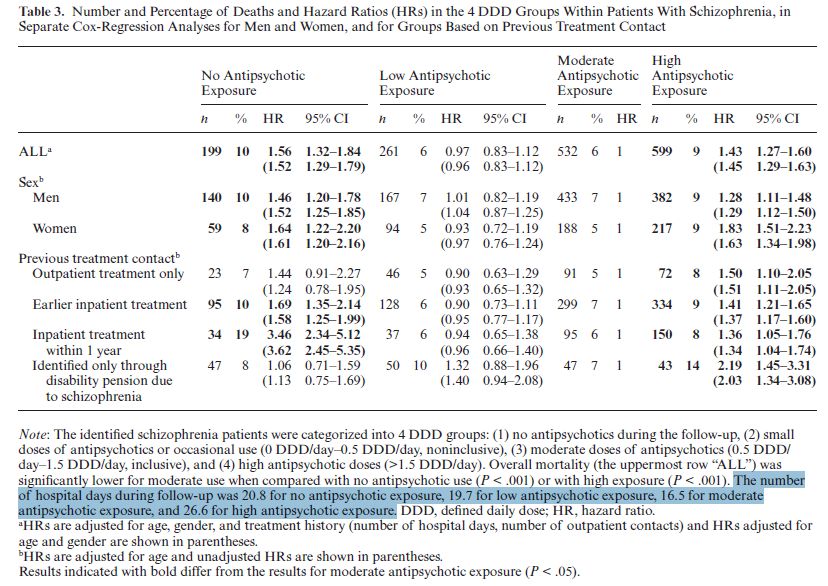

3. The finding that “the highest overall mortality was observed among patients with low antipsychotic exposure…” is an over-simplification. In fact, some of these individuals had a particularly low hazard ratio, while others had a particularly high hazard ratio. This can be seen clearly in Table 3:

In this table the moderate use group is used as the reference point. This is why all the hazard ratios for that group are 1. Hazard ratios for the other exposure groups are calculated as compared to the moderate group.

Here again, we see (top line) that the highest overall hazard ratio is for the zero-use group (1.56); next the high-exposure group (1.43); then the low-exposure group (0.97). The actual numbers differ from the earlier hazard ratios because those were calculated in reference to the matched controls, whereas the ratios in Table 3 are calculated in reference to the moderate-use group

Although the authors were unable to obtain information on drug prescriptions during hospital stays, they were able to determine whether a participant had been hospitalized and when. This is why they were able to calculate the hazard ratios for individuals who had had inpatient treatment prior to the follow-up period. Note that the hazard ratios for zero-users who had had previous inpatient treatment are high: 3.46 for people who had had treatment within the year prior to follow-up and 1.69 for those who had inpatient treatment earlier. And also note that the hazard ratio for the zero-users who had had no treatment, but were identified only from disability pension rolls, is relatively low: 1.06. The hazard ratio for the high users in the same category is 2.19. So the authors’ conclusion that the highest risk of death was “among those patients with no antipsychotic use”, is not the whole truth. The group with the highest risk consists of those individuals who had zero exposure to the drugs and who had had inpatient treatment within the previous year. The zero exposure individuals who had no record of formal treatment had a much lower risk ratio (1.06). This, of course, doesn’t prove that treatment is causing excess mortality, but it is at least as noteworthy as the U-shaped curve highlighted in the authors’ conclusion.

4. As indicated earlier, it is widely accepted that prolonged use of neuroleptic drugs reduces life expectancy, and that these toxic effects continue to impact mortality rates as long as the individual continues to take the drugs. To adequately monitor and study this effect, it is, I suggest, particularly important to include older people in the research. In this study, however, only individuals below the age of 65 were included. This will almost certainly have the effect of artificially lowering the mortality rate for the neuroleptic users. The senior years are precisely the time when one would expect to see the toxic effects of a drug become most evident. The authors provide no rationale for setting this upper age-limit.

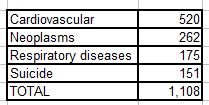

5. The total number of deaths in this study was 1591. Causes of death were given as follows:

This leaves 483 deaths unaccounted for. The authors tell us how the 1,108 deaths break down by exposure category, but we are given no information on the other 483 deaths. This is 30% of the total. We don’t know how these people died, nor how their deaths were distributed among the four exposure groups.

I wrote to Jari Tiihonen, the correspondence author, for information on this matter. In his reply, Dr. Tiihonen stated that this information was not available. It is possible that the 483 “missing” deaths were distributed across a large number of relatively low frequency causes. Studies of this kind often use an “Other Cause” category to capture this information. The complete absence of information on these deaths in this study, however, is noteworthy.

6. Perhaps the most serious problem with the study lies in the method that was used to define the four exposure groups. Let’s go back to a statement made in the “methods” section of the abstract:

“Total and cause-specific mortalities were calculated as a function of cumulative antipsychotic exposure from January 2006 to December 2010.”

My initial interpretation of this sentence, and I think it’s the interpretation that most people would make, is that mortalities were calculated during the follow-up period 2006-2010, and these mortalities were compared to lifetime cumulative drug exposure. In fact, as becomes clear later in the text, this is not what was done.

“The identified schizophrenia patients were categorized into 4 DDD groups; (1) no antipsychotics during the follow-up, (2) small doses of antipsychotics or occasional use (0 DDD/ day–0.5 DDD/day, noninclusive), (3) moderate doses of antipsychotics (0.5 DDD/day–1.5 DDD/day, inclusive), and (4) high antipsychotic doses (>1.5 DDD/day).” [Emphasis added]

So the individuals in the study were categorized – not by cumulative lifetime exposure to neuroleptics, but only by exposure during the five-year follow-up period. For example, a person who had been taking neuroleptics for decades, and came off the drugs in December 2005, and died in January 2006, would have been recorded as a mortality in the zero neuroleptic exposure group.

The phrase “cumulative antipsychotic exposure”, which occurs five times in the article, suggests lifetime exposure, and in my view the authors did not adequately emphasize the fact that the exposure data was actually limited to a five-year period. This strikes me as particularly pertinent, in that it is precisely the long-term cumulative exposure to these drugs that is the primary cause of the mortality concerns. The fact is that the present study provides no information on the effects of cumulative lifetime exposure to neuroleptic drugs.

PRESENTATION OF DATA

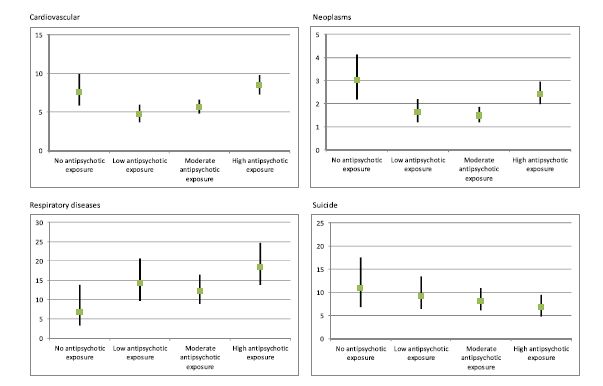

Here’s a copy of the authors’ Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Mortality expressed as hazard ratios due to specific causes in patients with schizophrenia compared with the control sample.

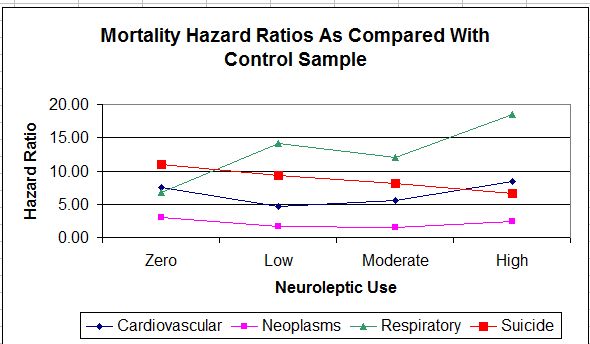

The mortality figures for respiratory illnesses show a generally upward progression from zero-use to high use. Figures for the other causes of death (cardiovascular, neoplasms, and suicide) show zero-use higher, or nearly as high, as high-use. But look at the scales on the left of each figure. The respiratory scale, which shows the neuroleptics in the worst light, is the tightest, and the cardiovascular scale, which shows zero use in the worst light, is the loosest. Here’s what the data looks like when all causes of death are graphed on the same figure and on the same scale.

As can be seen, the U-shape becomes a good deal less evident. The neoplasm line is fairly flat. The death rate for respiratory illnesses is increasing markedly with increased drug use. The suicide rate is sloping in the opposite direction. Only the cardiovascular line is identifiably U-shaped: a finding for which I can suggest no particular explanation, though it does seem unlikely that it reflects a lack of neuroleptic drugs. More likely, it reflects the fact that the zero use group were not really zero use.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions from the abstract were quoted earlier, but there is a more detailed conclusions section in the text of the article.

“Patients with low or moderate antipsychotic exposure have substantially lower overall and cardiovascular mortality than patients with no exposure or high exposure, which clearly indicates that both excess overall and cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia is attributable to other factors than long-term antipsychotic treatment when used in adequate dosages. An alarmingly high excess mortality among first-episode patients who do not use any antipsychotics deserves more attention, in order to increase adherence to their prescribed pharmacological treatment. Despite the importance of nonadherence, clinicians spend too little time on addressing this issue. For example, long-acting antipsychotic injections (LAIs) are associated with about 60% lower all-cause discontinuation than corresponding oral formulations among first-episode patients. Thus, more use of LAIs might result in substantially lower excess mortality. Focusing more attention particularly on first-episode and recently hospitalized patients who are not using any antipsychotics, and on patients with antipsychotic doses higher than 1.5 DDD/day, is essentially important in the prevention of premature death in people with schizophrenia.”

And there it is: people who don’t use the drugs have higher mortality, so steps must be taken to ensure adherence. And this conclusion is being promoted even though the identification of individuals with zero cumulative exposure was seriously flawed and unreliable.

AND INCIDENTALLY

The final author listed in the article is Jari Tiihonen. Dr. Tiihonen works for the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Finland; the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden; and is Professor and Chairman, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Eastern Finland.

Though he is not identified as such, it is fairly clear that Dr. Tiihonen is the senior investigator in the present study. He is identified as the correspondence author, and he is the Team Leader of the Center for Psychiatric Research at the Karolinska Institutet.

In the present paper it is acknowledged:

“In the last 3 years J.T. [Jari Tiihonen] reports serving as a consultant to Lundbeck, Organon, Janssen-Cilag, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, F. Hoffman-La Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; he has also received fees for giving expert opinions to Bristol-Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline, and lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Lundbeck, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Novartis; he is also a member on the advisory board of AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Otsuka, and he has received a grant from the Stanley Foundation.”

CITATIONS

The article didn’t attract a great deal of attention. But I did find three interesting citations.

Joel Yager, MD, psychiatrist, writing in the NEJM Journal Watch wrote:

“Even though this observational study cannot prove causality, the notably higher mortality among patients with no antipsychotic exposure suggests that adherence-increasing interventions, including use of long-acting injectable medications, might reduce risk for death.” [Emphasis added]

And schizophrenia.com:

“Antipsychotic Treatment and Mortality in Schizophrenia: No Drugs = Higher Mortality“

And Joanna Lyford writing on Medwire News:

“The relationship between antipsychotic use and mortality in people with schizophrenia shows a clear U-shape curve, with the highest risk of death seen in those with no antipsychotic exposure, a Swedish cohort study has found.” [Emphasis added]

None of the articles mentioned the fact that the results applied only to those individuals who had received prior treatment (particularly inpatient treatment), and was not evident at all in people with no record of treatment. Nor did any of the articles mention the fact that the “cumulative antipsychotic exposure” applied only to the five-year follow-up period, and that neuroleptic use prior to that period was not considered.