On November 18, 2015, Dr. Pies sent his response to my November 17 article to MIA. MIA posted it, and forwarded a copy to me. It reads:

“I have read Dr. Philip Hickey’s 8400+ word treatise, and I have only the following to say with regard to the two key points at issue:

- Notwithstanding my omission of quotation marks in my original Medscape article [1]—for which I take responsibility—the fact remains: I have never believed or argued that the so-called chemical imbalance theory (which was never really a theory) is merely a “little white lie.” It is that point of view—not merely typed words on the page—that has been falsely and carelessly attributed to me.

- I have never received a dime from any pharmaceutical company or private agency with any verbal or written understanding that I would “promote” (elevate, popularize, hype, etc.) a particular drug. If any of the papers I wrote or co-authored over a decade ago had the effect of putting a drug in a favorable light, it was because the best scientific evidence available at that time supported the drug’s benefit. Nothing in Philip Hickey’s belaboring of half-truths, innuendos and guilt by association demonstrates otherwise.

Sincerely,

Ronald Pies MD

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I had ended my November 17 article on a questioning note:

“But I’m also a realist, and I recognize the obvious fact that we are all capable of being biased in respect of our own writings. I am open to suggestions concerning this matter, and if Dr. Pies were to specify which statement or statements on my part have generated a sense of grievance on his, I would be happy to take another look at the document. And if, in the light of such re-examination, Dr. Pies’ expressions of concern are credibly vindicated, then I will apologize publicly, and retract the statement(s) in question.”

So the first thing that needs to be noted is that Dr. Pies hasn’t given me much to work with.

THE CHEMICAL IMBALANCE AND THE LITTLE WHITE LIE

He tells us now that despite what the “words on the page” might have conveyed, he has never “believed or argued” that the chemical imbalance theory is merely a “little white lie.”

And here, it has to be acknowledged, that Dr. Pies is making a very good point: that the words and the idea conveyed aren’t always the same thing. One could believe and argue that the chemical imbalance theory was a little white lie without every using those precise words.

So let’s try to phrase the question without using the words “little white lie”. A “little white lie” is an inconsequential falsehood, told to avoid causing embarrassment or hurt. So the question becomes: did Dr. Pies believe, or argue, that the chemical imbalance hoax was an inconsequential falsehood, designed to shield individuals from embarrassment or hurt?

Of course, I have no way of knowing what Dr. Pies believes. Nor, to the best of my recollection, have I even speculated on such matters. But I do know that he has argued that the chemical imbalance theory is an inconsequential falsehood designed to shield individuals from guilt and self-blame. Indeed, I provided an example of this in the November 17 article.

Here’s the quote from Dr. Pies’ August 4, 2001 post titled Doctor, Is My Mood Disorder Due to a Chemical Imbalance?:

“Many patients who suffer from severe depression or anxiety or psychosis tend to blame themselves for the problem. They have often been told by family members that they are ‘weak-willed’ or ‘just making excuses’ when they get sick, and that they would be fine if they just picked themselves up by those proverbial bootstraps. They are often made to feel guilty for using a medication to help with their mood swings or depressive bouts.…So, some doctors believe that they will help the patient feel less blameworthy by telling them, ‘you have a chemical imbalance causing your problem.'”

My reading of this passage is that Dr. Pies is saying that the chemical imbalance theory is an inconsequential falsehood designed to shield individuals from guilt and self-blame. Here’s another quote from the same paper:

“My impression is that most psychiatrists who use this expression feel uncomfortable and a little embarrassed when they do so. It’s a kind of bumper-sticker phrase that saves time, and allows the physician to write out that prescription while feeling that the patient has been ‘educated.’ If you are thinking that this is a little lazy on the doctor’s part, you are right. But to be fair, remember that the doctor is often scrambling to see those other twenty depressed patients in her waiting room. I’m not offering this as an excuse–just an observation.”

But, in fact, excusing the doctor’s actions is precisely what Dr. Pies is doing. The doctor tells the falsehood, which is just a “bumper-sticker phrase” anyway, because she’s “a little lazy”, and has twenty other depressed patients in her waiting room. In other words, the assertion is an inconsequential, and eminently excusable, falsehood. And, in passing, I might add that over the years I have heard a great many psychiatrists assert unequivocally that depression is caused by a neurochemical imbalance, and I have never detected in any one of these individuals the slightest hint of embarrassment or discomfort.

And here’s yet another quote from Dr. Pies’ same paper:

“Ironically, the attempt to reduce the patient’s self-blame by blaming his brain chemistry can sometimes backfire. Some patients hear ‘chemical imbalance’ and think, ‘That means I have no control over this disease!’ Other patients may panic and think, ‘Oh, no—that means I have passed my illness on to my kids!’ Both of these reactions are based on misunderstanding, but it’s often hard to undo these fears.”

Now to me, it seems self-evident that if a psychiatrist tells a client:

Your depression is caused by a chemical imbalance in your brain

and if the client interprets this as indicating that he or she has no control over the depression (other than by ingesting drugs), and worries that he/she might pass this imbalance on to his/her children, this is not a misunderstanding. This is an absolutely valid and reasonable inference from the psychiatrist’s statement. To describe this inference as a misunderstanding on the client’s part is simply another attempt to exculpate psychiatry in this hoax, and to downplay the magnitude of the deception, and the damage and destruction it has wrought. It also, incidentally, betrays a truly extraordinary degree of condescension towards the client.

So Dr. Pies has argued that the chemical imbalance theory is an inconsequential falsehood for which psychiatry carries minimal, if any, blame. But, apparently, he now wishes to distance himself from this position.

Which raises the question: what is Dr. Pies’ present position on the chemical imbalance theory?

And here we have solid, reliable, up-to-date information. On April 11, 2014, Dr. Pies amended the “little white lie” phrase in the “Nuances…” article at Psychiatric Times to read “simplistic notion”, and some time between October 15 and November 5, 2015, he amended the Medscape version to read: “simplistic formulation”. Both phrases mean much the same thing: an oversimplification.

And this is important, because Dr. Pies is not acknowledging that the chemical imbalance theory is false; just that it is an oversimplification.

However, the statement “Depression is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain” is not an oversimplification. It is simply false. To describe the chemical imbalance hoax as a simplistic notion is yet another psychiatry-exculpating attempt on Dr. Pies’ part. By promoting the chemical imbalance theory, psychiatry wasn’t just guilty of oversimplifying. Psychiatry was perpetrating a monumental hoax: a deliberate, self-serving deception, with widespread destructive and disempowering effects, which continue to this day.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

With regards to the Medscape article, Dr. Pies tells us that he accepts “responsibility” for the omission of quotation marks. But in fact, he doesn’t take this responsibility at all. Instead, he continues to berate his critics for “falsely and carelessly attributing” to him material that he actually wrote.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Pies tells us that he has never received payments from “any pharmaceutical company or private agency with any verbal or written understanding” that he would promote a particular drug. This is an interesting statement, of course, but its relevance in this context is not clear, because neither Drs. Lacasse and Leo, nor I, have ever alleged anything to the contrary. In fact, we’ve all taken particular pains to make this clear.

“We want to be clear that we are not accusing Ronald Pies of anything. Conflicts-of-interest are routine in academic psychiatry and many of the major pharmaceutical companies have been fined in the recent past. We do believe that readers deserve to know of his past financial relationships with the drug companies that promoted their products as correcting a chemical imbalance. The details of these financial relationships are not publicly available.”

And I, in the November 17 article, wrote:

“Dr. Pies could, of course, respond to all this by stating that he helped promote Lamictal on its merits alone, and that this promotion had nothing to do with the funding and/or manuscript assistance that he coincidentally received from the manufacturer of this product (GlaxoSmithKline). And he could contend that he cited the studies by Drs. Calabrese and Bowden purely on their merits. And all of this could well be true.”

So I’m not sure why Dr. Pies felt the need to deny activities of which he has not been accused.

Dr. Pies continues:

“If any of the papers I wrote or co-authored over a decade ago had the effect of putting a drug in a favorable light, it was because the best scientific evidence available at that time supported the drug’s benefit. Nothing in Philip Hickey’s belaboring of half-truths, innuendos and guilt by association demonstrates otherwise.”

With regards to this assertion, let me state at the outset that Dr. Pies is absolutely correct, in that there is nothing in my November 17 article that asserts, or even suggests, that Dr. Pies had entered into a specific agreement to promote a drug in return for payment. Nor is there anything in my article that demonstrates that Dr. Pies was guided by anything other than “the best scientific evidence available.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For these reasons, Dr. Pies’ insistence that his favorable comments concerning drugs were always supported by the “best scientific evidence available at that time”, struck me as an interesting challenge. So I pulled up one of the articles that I had mentioned in the November 17 post.

The article is “Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders“, by Drs. Pies and MacKinnon. The article is a literature review/opinion piece, published in Bipolar Disorders 2006: 8: 1-14. Here’s a quote:

“To our knowledge, there are only two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of anticonvulsants in well-defined rapid cycling populations, both by the same group, and only one currently in the literature (59). In the published study, 182 rapid cycling patients were randomized to lamotrigine [Lamictal] monotherapy or placebo. The study found that 41% of lamotrigine-treated versus 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy.”

Reference 59 was a GSK funded study by Dr. Calabrese et al (2000). This is the same Dr. Calabrese who was mentioned in the United States vs. GSK 2012 lawsuit. (See my November 17 article for details.)

It is clear in this quote that Dr. Pies is indeed putting lamotrigine “in a favorable light”, but the evidence presented in the study does not support the conclusion. In fairness to Dr. Pies, the claim to efficacy is asserted in the study’s abstract:

“Forty-one percent of lamotrigine patients versus 26% of placebo patients (p = .03) were stable without relapse for 6 months of monotherapy.”

In fact, as can be seen, Dr. Pies has quoted the above statement almost verbatim. But the assertion is not justified by the evidence presented in the study. It’s a complicated piece of research, but here’s the gist.

Three hundred and twenty-four individuals were enrolled in the preliminary phase of the study. During this phase, participants were prescribed lamotrigine [Lamictal]. Initially they could take other psychotropic drugs also, but after 4-8 weeks of exposure to lamotrigine, “…all other psychotropic medications, including lithium, were tapered provided that patients met the criteria for wellness.”

Participants were eligible to enter the second phase of the study

“if they successfully completed the taper [from other drugs] while maintaining the minimum criteria for wellness, had no change in lamotrigine dosage during the final week of the preliminary phase, and had no mood episodes requiring additional pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) after the first 4 weeks of the preliminary phase.”

From the initial pool of 324 participants, 182 met the above criteria and moved to the second (randomized) phase.

The second phase was scheduled to last for 26 weeks. The researchers focused on three possible outcomes:

- completion of the 26-week period without additional pharmacotherapy

- completion, but with additional pharmacotherapy

- withdrawal from study (e.g., because of adverse events, consent withdrawn, lost to follow-up, etc.)

So to summarize: during the first phase, the researchers identified 182 participants who were taking only lamotrigine, and met the study’s “criteria for wellness”. Then, at the beginning of the second phase, they switched approximately half of these individuals, randomly selected, to placebo.

“At the start of this phase, patients immediately discontinued open-label lamotrigine and began double-blind treatment with lamotrigine or placebo. Lamotrigine and matching placebo were supplied in 100-mg dispersible tablets and administered orally once daily.” [Emphasis added]

The primary outcome variable in this study was the need for

“additional pharmacotherapy for a mood episode or one that was thought to be emerging.” [Emphasis added].

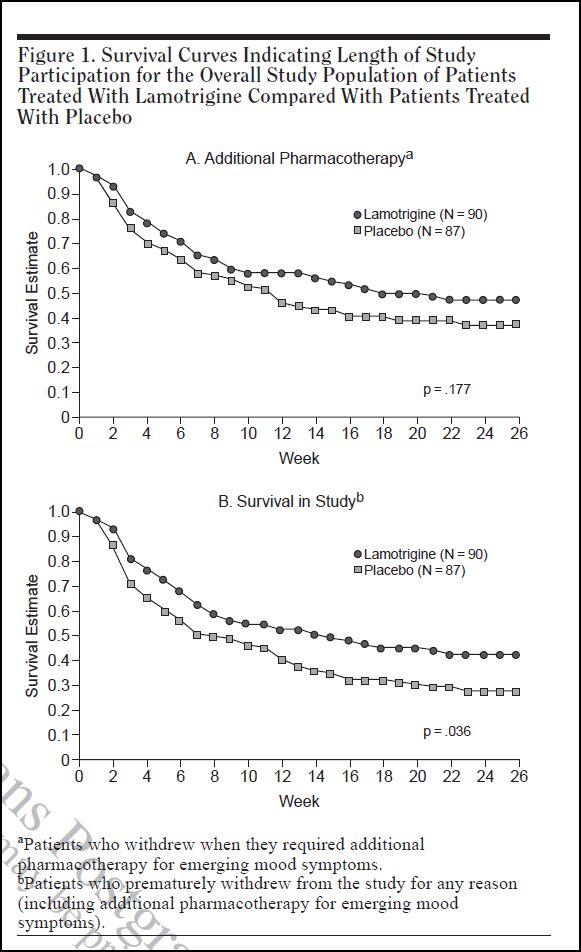

Figure 1 shows the main results.

These are survival graphs. Survival in this context does not refer to life vs. death, but rather to survival in the study. In the upper graph, the criterion for non-survival is the perceived need, and prescription of, “additional pharmacotherapy”. In the lower graph, the non-survival criterion is drop-out for any reason, including the need for “additional pharmacotherapy”. Other reasons given for drop-out were: adverse events, withdrawal of consent, lost to follow-up, protocol violation, and other.

Survival in each graph is plotted against time (in weeks) on the horizontal axis. At the beginning of the study, all participants in both graphs show a survival rate of 1.0 (or 100%). With each passing week, some individuals are dropped, either because they needed additional pharmacotherapy (upper graph, A), or for any reason, including additional pharmacotherapy (lower graph, B).

As can be seen, the lamotrigine group has a consistently higher survival rate than the placebo group. In graph A, this difference does not reach statistical significance. There is a 17.7% probability that the difference might have arisen by chance alone. But in graph B, the difference is more marked, and there is only a 3.6% probability that the difference could have arisen by chance. The 41%-26% disparity mentioned in Dr. Pies’ article is the difference in final survival rates in Graph B. If one refers across from the tail points of the two graphs to the vertical axis, one can read that the lamotrigine group has a final survival rate of 41%, and the placebo group 26%.

So, one might conclude from all this that lamotrigine is indeed more efficacious than placebo in this context, and that 41%-26% disparity reflects the magnitude of this difference. But there are three problems with the study. Firstly, there is a marked withdrawal effect evident in the survival graphs. Secondly, the study’s primary criterion was not relapse as such, but rather a concern that relapse might be emerging. And thirdly, the participants who dropped out for any reason were counted as having relapsed.

THE WITHDRAWAL EFFECT

If you look carefully at the graphs, you will notice that the attrition rate for the placebo group, in both graphs, is steepest during the first three weeks of the study, i.e. for the three weeks after these individuals have been precipitously taken off lamotrigine.

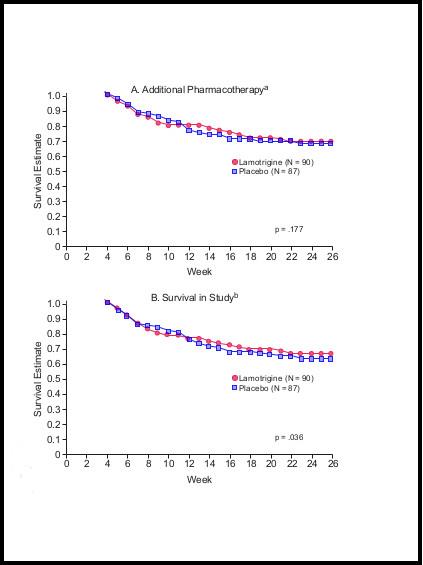

It is clear from inspecting the graphs that if this very high attrition rate had not occurred, or had been discounted from the research, the survival graphs for the remainder of the 26 weeks would be virtually identical. To demonstrate this, I have redrawn both graphs omitting the data from the first three weeks. So, starting with week four, I moved both graphs up the page to the 100% starting point, without altering their relative shapes/contours. The results are shown below. As can be seen, the survival rates for the lamotrigine group and the placebo group are virtually identical for both criteria. I don’t have the raw data from which statistical significance could be assessed, but the graphs speak for themselves.

Modified Graphs

What we are actually seeing in this study is a fairly marked withdrawal effect. And in fact, the authors mentioned this possibility, in the Discussion section, though with considerable downplay.

“At the time of randomization, patients assigned to placebo had open-label lamotrigine abruptly discontinued. Although rebound relapse into a mood episode after the abrupt discontinuation of lamotrigine has been reported in neither the neurologic nor psychiatric literature, this methodological feature remains a possible confound.” [Emphasis added]

But, in the “Affective Instability…” paper, Dr. Pies makes no mention of this possible confound, which actually nullifies the authors’ conclusions.

The conclusion that should have been drawn from the Calabrese et al study was that, apart from those individuals who “crashed” within the first three weeks following abrupt discontinuation of lamotrigine, there was no difference in efficacy between lamotrigine and placebo. The presence of the marked and obvious withdrawal effect in this study is the more notable in that it would have been a very simple matter to safeguard against this. All that was needed was to build in a three or four week taper at the start of each placebo trial. This could have been done without breaking the blind, as both lamotrigine and placebo were given in identical tablets.

Incidentally, there’s an interesting discussion of withdrawal-related relapse in Joanna Moncrieff’s book, The Myth of the Chemical Cure, palgrave macmillan, 2009 (p 191-194).

DEFINITION OF RELAPSE

Here’s how the study’s authors defined the word relapse:

“…for the purpose of this study, relapse was operationally defined as the need for additional pharmacotherapy for a mood episode or one that was thought to be emerging.” [Emphasis added]

Ordinarily, in medical circles, the term relapse means a recurrence of the illness in question, and in psychiatric circles this would mean – in the case of “bipolar disorder” – a recurrence of what psychiatrists call “a mood episode”, either depressive, hypomanic, or manic. But this is not how Drs. Calabrese et al used the term. For them, an indication that a mood episode might be “emerging” was the threshold criterion. And lest there be any doubt on this matter:

“The design of this study did not permit an analysis of time to relapse into a full episode of depression, hypomania, or mania since patients were withdrawn at the first signs of relapse.” [Emphasis added]

So when Drs. Pies and MacKinnon wrote that

“41% of lamotrigine-treated versus 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy”

they were exceeding the evidence, in that stability without relapse, in the ordinary and customary sense of the term, was not the criterion against which the 41%-26% disparity was established. The study provides no information at all on the matter of stability without relapse.

The study write-up does not tell us precisely what kinds of presentations would be considered grounds for believing that a “mood episode” might be “emerging”. But it does seem likely that lamotrigine withdrawal effects would qualify. Drugsdb.com gives the following “commonly reported” withdrawal symptoms for lamotrigine.

- Anger, Rage or Hostility

- Headaches

- “Brain flashes” or “Brain zaps”

- Tingling in areas around the body

- Thoughts of Suicide and Other Irrational Thoughts

- Dizziness

- Severe Depression

- Vivid Dreams and Nightmares

DROP-OUT VS. RELAPSE

The 41%-26% efficacy claim is based on the further assumption that all the individuals who dropped out because of adverse events, withdrawal of consent, lost to follow-up, protocol violation, and other, relapsed. Here’s how the study authors justify this assumption:

“Bipolar disorder is a disorder of impulse control and impaired judgment, and poor compliance is a frequent consequence of both. We therefore hypothesized that premature treatment discontinuations are related to early signs of relapse. Thus, one clinically relevant measure of efficacy is survival in the study to the point of withdrawal for any reason.” [Emphasis added]

Which strikes me as tenuous at best. One could just as validly hypothesize that the individuals concerned didn’t relapse, and were doing fine. And besides, even if withdrawal for any reason is “one clinically relevant measure of efficacy”, it is not the same thing as relapse. And a higher rate of stability without relapse is what Dr. Calabrese et al and Dr. Pies and MacKinnon claimed for lamotrigine.

This is a critical issue, because the individuals who dropped out are over-represented in the placebo group (19% vs. 12%), so including these participants in the relapse group was a clear bias in favor of lamotrigine.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CONCLUSION

Dr. Pies’ statement in the “Affective Instability…” article:

“The study [Calabrese et al, 2000] found that 41% of lamotrigine-treated versus 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy”

has the effect of putting lamotrigine in a favorable light. The statement is also an accurate echo of what Dr. Calabrese et al stated in their abstract, but it is not supported by the evidence set out in the study. Specifically, the above conclusion is nullified by strong indications of marked withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group, and by a non-standard definition of relapse. Both of these factors had the effect of suppressing the calculated survival rates among placebo participants, and consequently inflating the perceived efficacy of lamotrigine.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I realize that this debate may have the appearance of a personal feud between Dr. Pies and myself. So I want to make it clear that, for my part at least, this is not the case. I don’t know Dr. Pies individually, nor have I the slightest interest in attacking him personally or wounding his reputation. My interest is, and always has been, psychiatry’s spurious concepts, its destructive and disempowering “treatments”, and its long history of fraudulent research. Sadly, Dr. Pies has adopted as his mission the defense of psychiatry, and it is perhaps inevitable that we should occasionally clash. But the target of my critique is psychiatry, not the individuals who promote and defend it.