I have recently read Psychiatry Interrogated, subtitled “An Institutional Ethnography Anthology”. Ethnography is the branch of anthropology that deals with the systematic study of individual cultures. Institutional ethnography (IE), according to Wikipedia, is “a method of social research [that]… explores the social relations that structure people’s everyday lives, specifically by looking at the ways that people interact with one another in the context of social institutions (school, marriage, work, for example) and understanding how those interactions are institutionalized…For the institutional ethnographer, ordinary daily activity becomes the site for an investigation of social organization.”

In the Introduction to Psychiatry Interrogated, Dr. Burstow writes:

“The suitability of IE as an approach for interrogating psychiatry is demonstrable for psychiatry routinely causes disjunctures – indeed, horrendous disjunctures in people’s everyday lives; it has both hegemonic and direct dictatorial power. Behind what we might initially see – a doctor or a nurse – lies a vast army of functionaries, all of them activating texts that originate extra-locally. The fact that IE as a method feels ready-made to unlock institutional psychiatry – and that’s what I am suggesting here – is not accidental. Significantly, from early on, psychiatry was one of the primary regimes which Dorothy [Dorothy E. Smith, PhD, (1926- ) founder of IE] was theorizing as she went about developing her method.” (p 10)

Although IE studies begin with a disjuncture or disconnect in people’s everyday local lives, the focus is on the impact of non-local institutions and texts.

It should be clarified at this point that IE studies are not the kind of statistical analyses that we normally encounter and discuss in this arena. Rather, they are qualitative descriptions of what’s going on in a situation with particular reference to relationships, power, and institutional oppression. IE enquiries are “particularly aimed at ferreting out and making visible how institutions work”. (p 5)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

All the chapters of Psychiatry Interrogated, except the Introduction and the Afterword, describe a specific IE enquiry in which the institution psychiatry is examined. In order to convey something of the flavor of the book, here is a brief outline of the disjunctures that initiated each enquiry, and some illustrative quotes.

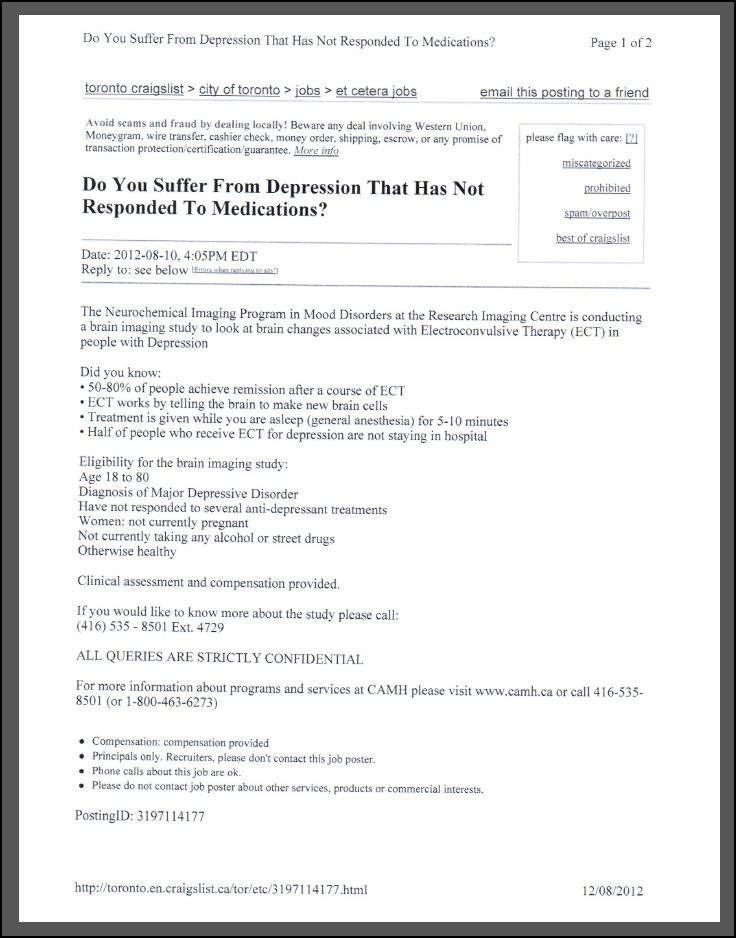

Chapter 2 (B Burstow and S Adam): In August 2012, the following ad appeared in the jobs etcetera section of the Toronto craigslist:

The authors point out that

“Under the category ‘Jobs Etc.’ CAMH had placed an ad on Craigslist that in essence functioned so as to lure those down on their luck to be participants in an electroshock study – a study that involved them actually receiving ECT. In the battle and research that followed, hitherto hidden truths come to light not only about psychiatric research processes but, every bit as important, about research oversight in general.” (p 16)

“At the same time as credible studies were establishing damage and disproving effectiveness, a mammoth ECT research industry devoted to demonstrating that the ‘procedure’ was safe and effective was moving into high gear – all overruling credible findings, all invisibilizing the everyday lives of shock survivors. Moreover, books that functioned as boss texts…were spearheading a ‘safe and effective’ narrative. By the same token, hospitals were making their reputation through ECT research. It is in this context that we must understand the ECT study.” (p 28)

Chapter 3 (C Chapman, J Azevedo, R Ballen, J Poole): Two nurses, who had practiced competently for years, lost their nursing certificates because they divulged a history of “mental illness”.

“It is the framing of Janet and Ikma as ‘mentally ill’ (conflated with ‘incompetent’) that enabled the CNO [College of Nurses of Ontario] to disregard their alternative accounts of events, their legitimate grievances, and assertions of their ‘competence.'” (p 58)

Chapter 4 (L Tenney in consultation with C Brown, K Cascio, A Cerio, B Grundfest-Frigeri): The disjuncture for this study is the psychiatrization of people on the grounds of their nonhegemonic spiritual beliefs.

“My standpoint, my entry into the research, is as someone who 28 years ago was involuntarily institutionalized and drugged in New York, at least in part because of my spiritual experiences. My ultimate disjuncture is precisely that psychiatrization. The question that I am asking is how does psychiatry operate so that such disjunctures or violations occur? That is, how does it turn people’s spiritual leanings into a warrant for both initial and ongoing psychiatrization?” (p 68)

Chapter 5 (MJ Hande, S Taylor, E Zorn) addresses the difficulties faced by parents of children “diagnosed with autism”, and examines how these parents, in their pursuit of assistance and resources, become unwitting agents of “the complex, multileveled ruling relationships that structure them”.

“At all levels of the process, parents can only access care and support through their child’s diagnosis and the texts that diagnosis has generated, thereby leading them to continually activate the DSM.” (p 90)

Chapter 6 (SL Jakubec, JM Rankin) examines how psychiatric expansionist goals can infiltrate, and even eclipse, the original goals of a helping organization.

“In our analysis we show how development practices (e.g., the exploration of indicators for measurement) and the dominant movement for global mental health (mGMH) – and goals of a rapid ‘scaling up’ of mental illness diagnosis, treatment and research – began to enter the way workers at the NGO understood and performed their work.” (104)

“The biomedical emphasis on ‘mental health’ has had an important impact on how ‘global mental health’ is being addressed. The mGMH’s premise is that what are called, for example, depression and schizophrenia, are biological disorders no different from HIV-AIDS or epilepsy, and that people living in poor countries have just as much right to access effective drug treatments for mental disorders as people in ‘developed’ countries…Despite the arguments of some experts claiming that drug treatments for psychiatric conditions are nowhere near as effective as believed…and are even harmful…those in the movement have relied on the appeal of equitable access to treatment to create the focus of the goals of the mGMH…What we see here is a conflation of human rights discourse and biological psychiatry discourse..” (p 108)

Chapter 7 (L Spring) begins with three disjunctures. Firstly, increasing numbers of soldiers are killing themselves; secondly, soldiers who are experiencing problems of living are being labeled as “mentally ill”; and thirdly, the “treatment” these individuals receive often causes severe and permanent harm.

“…the question arises: Could some soldiers have killed themselves not in spite of the treatment they were receiving, but because of its effects? Should not the fact that more than half of the CAF [Canadian Armed Forces] members who killed themselves in 2013 were receiving ‘the best care this country has to offer’ at the time of their suicides be an indication that the current system is not working?” (p 133-134)

“This chapter has traced how it has come to pass that a fictional disorder ‘essentially created by committees of doctors sitting around conference tables’…has gained so much traction in recent years. I have traced how the ruling relations continually associate the idea of PTSD with soldiers’ suicides and how the language of the DSM is now regularly activated. This is done not only by the media, the military, and the psychiatric system itself but also by services members, veterans, and those closest to them as they go about their daily lives.” (p 140)

Chapter 8 (J Tosh, S Golightley) presents two instances of bullying in UK colleges. In one case the victim came to be labeled as “mentally ill”; in the other, the victim was bullied because of such a label.

“These two case studies illustrate how labels of ‘mental illness’ can be used to silence those who speak out against oppression and pathologization within those professions where such interventions are sorely needed. In one case, violence and bullying was dismissed, ignored, and perpetuated by labeling the victim as ‘mentally ill.’ In doing so, her accusations of bullying and her competency regarding her job became discredited and disbelieved. Her actions and words were constantly interpreted and viewed through the lens of sanism and used as further justification for abuse.” (p 156)

“In the other case, the label of ‘mental illness’ was framed as a ‘danger’ and a ‘risk’ in addition to a ‘vulnerability.’ However, rather than provide the assistance that was initially requested, her label of mental illness was used in attempts to disrupt her training, much like how Olivia was ‘pushed out’ of her job. This, in addition to the increased surveillance in both cases, shows how ‘reasonable adjustments’ manifested as restrictions framed within a discourse of ‘help’ and doing what was ‘best’ for those with a ‘mental illness.'” (p 156)

Chapter 9 (R Wipond, S Jakubec) examines the development of workplace “mental health” and the reframing of social problems as psychiatric issues.

“…the dominant Western mental health system is itself a deeply contested space characterized by polarized power relationships between the providers and the people actually receiving the ‘treatments’ or services. In addition, profound political tensions are built into federal, provincial, and state laws that allow assertive, coercive, and forced ‘mental health care.'” (p 163)

“…extremely divergent opinions and struggles for power emerge in the scientifically unvalidated diagnostic methods and the often unreliable, ineffective, and demonstrably dangerous treatment practices…” (p 163)

These observations prompt the authors to ask:

“…could importing principles, policies, and practices from the mental health system into workplaces truly, as suggested, ‘create and continually improve a psychologically healthy and safe workplace?'” (p 163)

Chapter 10 (A Doll) examines the system by which people being adjudicated for involuntary psychiatric admission are afforded legal representation in Poland. The study begins with three disjunctures that will be familiar to anyone who has had contact with these matters. Firstly, the lawyers are poorly compensated for their work; secondly, they are mandated to perform this work; and thirdly, “it is almost impossible to challenge” psychiatric assertions in a legal context.

“All of which – even for those lawyers committed to their legal aid duties – only adds to the already burdensome nature of the work. The key issue here is that the involuntarily admitted – that is, the very persons who need spirited lawyering – may not receive appropriate advocacy. In this context, a right to representation, a key guarantee of ‘due process’ under the inherently coercive procedure of involuntary admission, may be nothing more than a formalistic legal institution with no substantive meaning.” (p 184) [Emphasis in original]

Chapter 11 (E Gold): The disjuncture that prompted this study was the author’s observation that the torture experiments conducted in the 60’s by John Zubek, PhD at the University of Manitoba, were funded, not only by the military, but also by the US National Institute of Mental Health.

“It was argued earlier that Zubek’s experiments meet the criteria of definition of torture. Students were knowingly and purposefully placed into experimental conditions that caused them pain and suffering. These experiments were sanctioned by the University of Manitoba, and the ethical regulatory body for the field of psychology, the CPA, never stepped in, thus creating the illusion that Zubek’s work met ethical standards. Zubek’s research was directly linked to military torture through one nagging question that he could never escape – if not torture, what was the DRB’s [Defense Research Board] interest in funding this research?” (p 219)

“Nevertheless, little research has questioned the interests of Zubek’s other major funder – the US National Institute of Mental Health. We now know that this research was linked to the development of current military torture techniques – methods that cause pain and suffering without inflicting direct physical violence on the victim. It seems worthwhile to ask here: What is the overlap between the development of military torture and the burgeoning field of mental health? If not torture, what was the NIMH’s interest in funding this research?” (p 219)

“Recalling the actual experiments, the National Institute of Mental Health primarily funded the immobilization branch – the most intolerable condition in Zubek’s repertoire. Although most research has focused on the sensory deprivation aspect of the experiments, it was the immobilization that most subjects were simply unable to bear. This condition – having one’s head and limbs strapped while in a recumbent position, even with normal levels of sensory input – was experienced as excruciating, with only one-fifth of the research subjects continuing their participation until the end. Not only was this condition intolerable to most participants, but it also produced intellectual stunting, a loss of contact with reality, and severe distortions in participants’ perceptions…It is worth noting that Zubek’s immobilization condition bears a striking and eerie resemblance to the common practice of physical restraint in mental health settings.” (p 219-220)

“Unlike Zubek’s subjects, however, individuals who are being forcibly restrained in a psychiatric context do not enjoy the option of deciding whether they consent to being restrained and how long this period of restraint should last.” (p 220)

In conclusion, the author poses the troubling question:

“Are we as a society going about our everyday lives while complicit in everyday atrocities disguised as ‘help’?” (p 224)

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF IE FOR ANTI-PSYCHIATRY

Psychiatry routinely presents itself as a legitimate medical specialty differing from the other specialties only in the kinds of illnesses treated. But, in fact, this is not accurate. Firstly, the problems that psychiatry purports to treat are not illnesses in any ordinary sense of the term; and secondly, psychiatry’s treatments are nothing more than legalized drug-pushing, more akin to the street-corner activity than medical care. But there is another important difference between psychiatry and real medicine. Psychiatry’s core concepts are embedded formally and informally in our legal, social, educational, and workplace institutions in ways that the other medical specialties are not.

The term “mental illness”, for instance, which most of us in the anti-psychiatry movement consider spurious, is written into the laws and regulations of every US state, and probably most other countries. In addition, virtually every county in the US is “served” by a publicly-funded community mental health center, charged with “treating mental illness”, educating the community on matters pertaining to “mental health”, and forcibly committing people to psychiatric facilities. Residents of nursing homes are required by federal law to be screened for “mental illness” on admission, and to be afforded “treatment” if this is indicated. Schools are legally required to provide special accommodation for some children who have been assigned spurious psychiatric labels (e.g. ADHD), and additional funding is provided for these activities. And at the present time, psychiatry is pushing hard for integration of its “services” into primary care.

Those of us who would like to see an end to psychiatry are aware of its widespread tentacles, and the extent to which its core concepts and practices are embedded in the very fabric of our society. But that awareness tends to be of the dull-and-persistent-ache variety, rather than the sharp-stone-in-the-shoe.

We win the intellectual and moral battles hands down, but we are understandably daunted at the prospect of persuading fifty legislatures that the term “mental illness” has no validity, and that psychiatric “treatment” is essentially on a par with street-corner drug-pushing.

We are daunted by the exportation of mental illness concepts and practices to all parts of the globe. We are daunted by the wholesale adoption of pathologizing and disempowering psychiatric ideas by the military services here in the US and abroad.

We touch on these, and related, issues frequently, of course, in our individual writings, but up till now, we have lacked a formal methodology to focus on these matters, and to lay bare the disjunctures, the intricacies, the details, and the damage done.

And it is in this regard that the value of Psychiatry Interrogated needs to be recognized. Psychiatry Interrogated does, of course, critique psychiatry, but it also does more: it provides and demonstrates a formal methodology (IE) by means of which these kinds of concerns can be systematically studied and credibly exposed in a wide variety of situations and contexts. Psychiatry Interrogated is a cardinal work in the literal sense of the term: a turning point on which new developments can hinge, find support, and thrive.

SUMMARY

Psychiatry Interrogated is a powerful and compelling work, that demonstrates how common reactions of the how-can-that-happen? variety can serve as springboards to unraveling and exposing the complex, repressive, and inherently destructive nature of psychiatry. Each chapter has an extensive reference list for those who wish to pursue any of the topics in greater depth.

The book is dedicated to “everyone everywhere who has ever fallen prey to institutional psychiatry.”

DISCLAIMER

I have no financial interest in this book or any book/product that I mention in these writings.