Recently I came across a remarkable article From surviving to thriving: how does that happen. The authors are Mark Bertram and Sarah McDonald, and the piece was published in The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, Vol 10, Iss 5, 2015. The work was conducted in the vocational service department of a large mental health center in London, UK.

The authors’ purpose was:

“…to explore what helped seven people in contact with secondary mental health services achieve their vocational goals, such as: employment, education, training and volunteering.”

Here are some quotes, interspersed with my observations and comments.

“It is widely recognised that people in contact with mental health services are one of the most excluded groups in society. The causes of this exclusion are complex, multifaceted and not completely understood, but the facts are stark. Employment rates have hit their highest since records began, yet the majority of service users are unemployed (Office National Statistics, Statistical Bulletin, 2015).”

“Current critiques of the care programme approach (CPA) and the care planning process state that the work of mental health services through CPA is generally not effective – in terms of helping people achieve their goals and enhancing their life experience. There are calls for a fundamental change to the nature of the relationship between service users and professionals – with an emphasis on partnership and collaboration (Rinaldi and Watkeys, 2014).”

In fact, psychiatric care is inherently disempowering. Telling people, falsely, that they have an incurable, disabling brain disease militates against the notion that they can pursue their goals and improve their situation.

“The role of the staff is collaborative – moving from doing to or trying to fix, to helping people find their own way forward by identifying the things people are able to do and encouraging choice and control within a trusting relationship. This has been described as hope inducing and promotes well-being (Rapp and Goscha, 2010).”

“There are continuous calls for new ways of working in mental health services and knowledge from service users to be given its rightful place (Basset, 2008; Beales, 2012; Faulkner and Basset, 2012). What remains less clear in the literature is what service users are actually saying? Specifically, what do service users say are the conditions that help them achieve their goals, increase their well-being and be included?”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The authors invited the service users at their center to come forward and be interviewed, with the objective of developing answers to the following questions:

“1. What areas of life were you struggling with prior to engaging in the peer support or vocational service?

2. What mental health services were you using and how was your mental health and well-being?

3. How were you involved in the project, what worked for you and what life changes have occurred as a result of engaging in peer support or vocational services?

Data analysis

The data were transcribed, content analysed and categorised under the key emerging themes. Validity checks involved giving the participants a copy of their interview with our interpretations. Some minor adjustments were necessary. Overall, the participants agreed that these records were accurate versions of their interview.

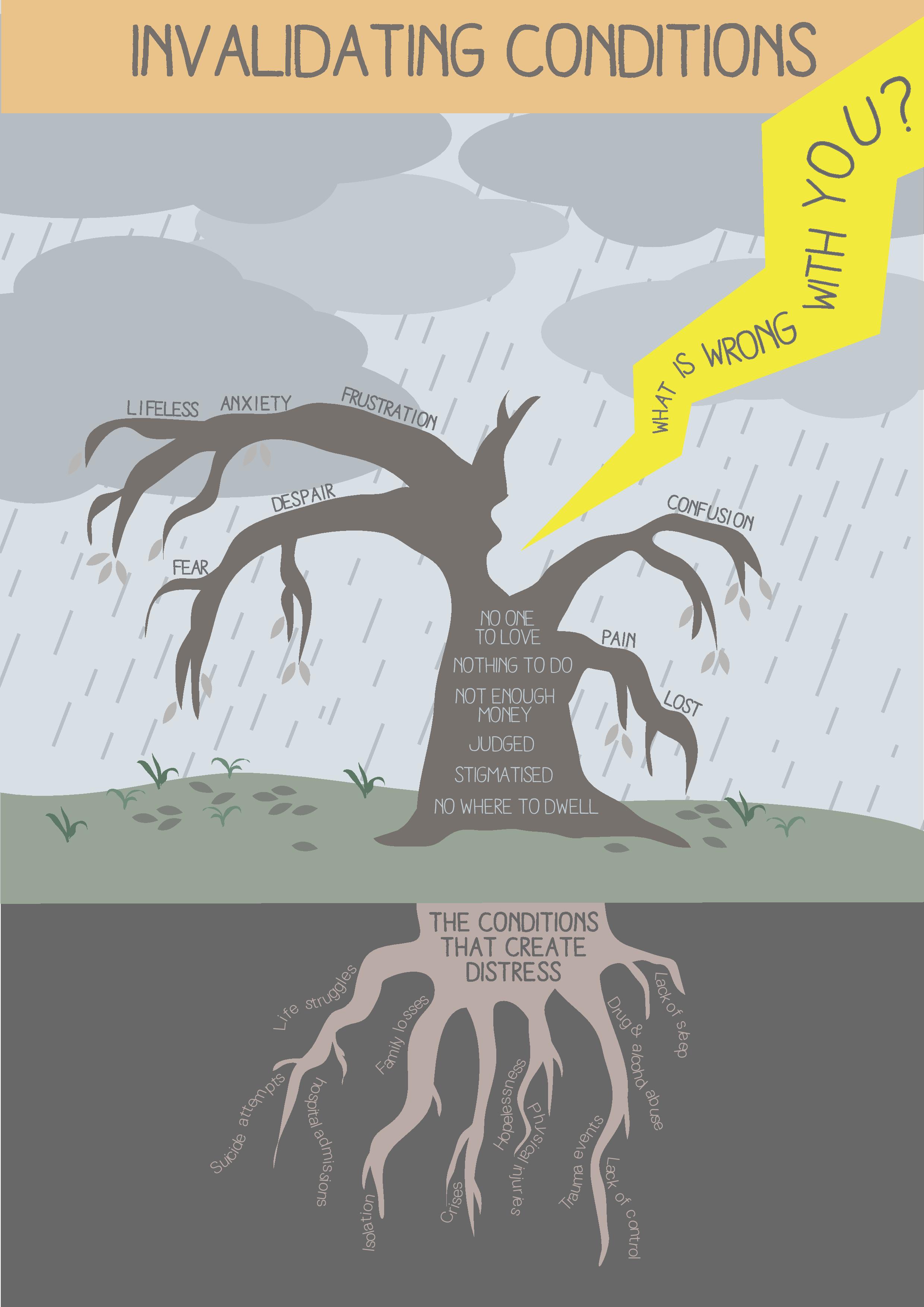

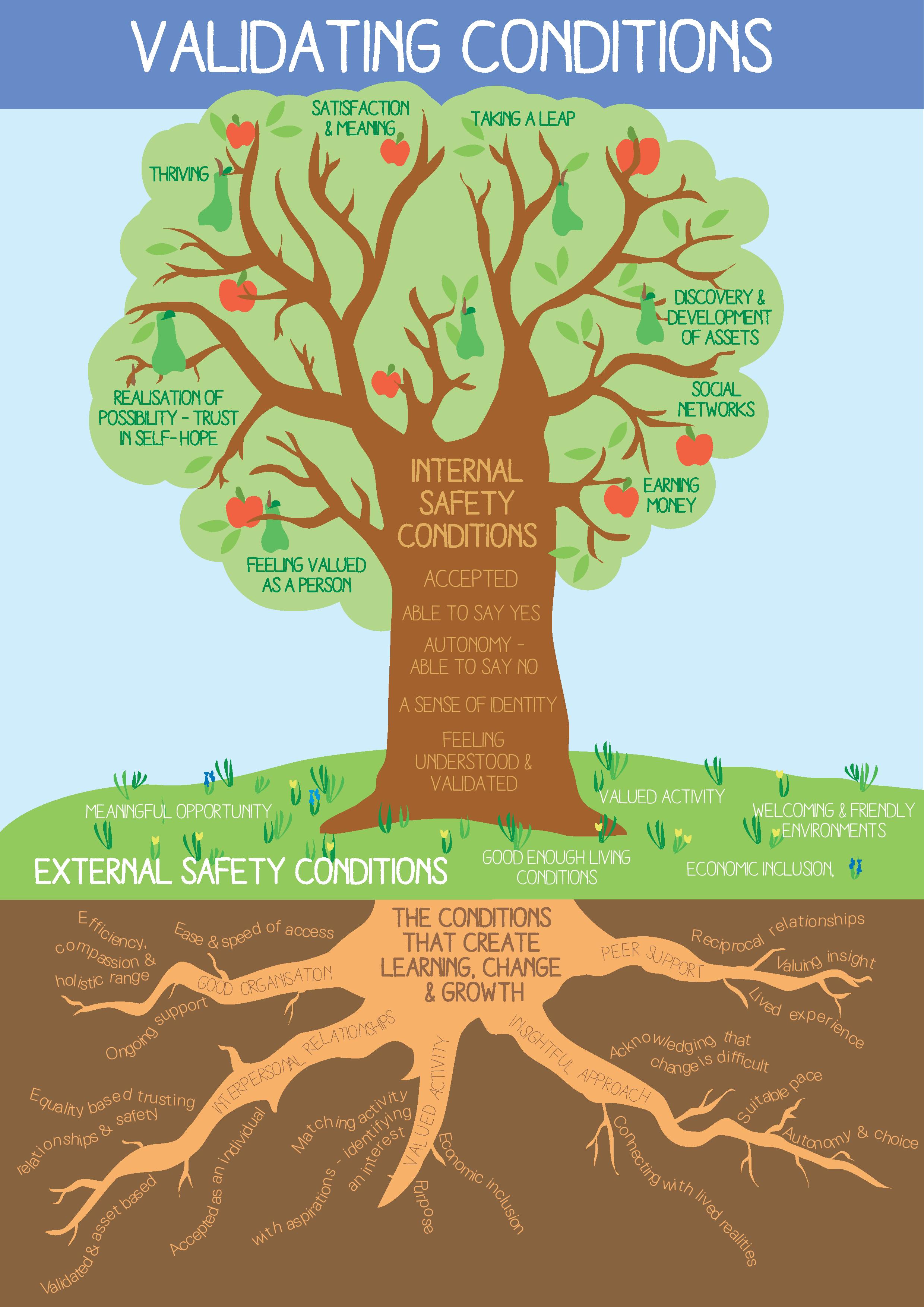

We then combined the qualitative data from all the interviews and through further reflection and content analysis we began to see patterns emerging – similarities between the nature and impact of people’s struggles and the types of conditions that people were saying helped them in a process of change and growth. These were listed on five pages of A4 [letter size paper] and consisted of 50 themes. To try and make the data clearer and more concise, we explored the possibility of creating images to visually represent the themes. We hired a systems designer and she was able to construct initial tree designs. We were then able to embed the themes into roots, trunk, branches and fruits.

We shared these images with staff, peer supporters and service users and the response was enthusiastic and positive. People were saying these images and the themes represented their understanding of the invalidating conditions that cause distress and the validating conditions that facilitate a process of learning, change and growth. Gradually, a model of change – with all its inter-related parts and processes – emerged and this remained faithful to the insights people shared.”

Here are the tree images:

Under the heading Life Struggles, the authors pointed out:

“People were saying their main struggles with their mental health were related to problems with living and these difficult life experiences had created significant distress over a number of years. Consequently, everyone we spoke with had ended up in secondary mental health services for over five years. One person had been in services for 20 years, including 11 annual admissions to hospital. These were bleak, harrowing and painful situations that people arrived with.”

In their Conclusion section, the authors note:

“People were very clear and identified a wide range of life struggles that brought them into contact with services such as: income poverty, unemployment, trauma events, serious physical injuries, bullying, isolation, drug and alcohol problems, family losses, stigma, meaninglessness, hopelessness and a lack of sleep. It was the invalidating effects of these struggles that caused serious damage.”

This is in marked contrast to the standard psychiatric approach, which is to downplay the significance of these kinds of adverse events and circumstances, and to tell the client that he/she has a brain illness which needs to be treated with chemicals and/or high voltage electric shocks to the brain.

“However, all of the people we interviewed found their own way through and there are several important threads that bound their stories together. How people were perceived and treated was simply everything. It was the human, can do and co-productive approach within the vocational and peer support projects that shone through.”

Under the heading Recommendations:

“The evidence here reveals that the difficulties that bring people into contact with mental health services are multifaceted, but have common themes – problems with living and being invalidated. The challenge for all mental health services is to recognise and address the economic, psychological and social consequences of these life struggles. If these areas are not addressed then the demand on services will continue to increase because the direct causes of distress are not being resolved.” [Emphasis added]

How simple and clear. In my experience, people who are despondent are always able to explain in clear, simple terms why they are feeling despondent. And it always comes down to adverse events and/or abiding adverse circumstances. Psychiatry, however, self-servingly wedded as it is to spurious biological explanations, ignores this entire area, and focuses solely on “making the diagnosis”. So instead of asking open-ended questions and allowing the client to talk, they ask the questions on their inane, simplistic checklists: how often do you feel depressed?; are you less interested in doing things than formerly?; have you lost or gained weight recently?; are you having trouble sleeping?; are you sleeping excessively?; do you feel slow or sluggish?; do you feel worthless or guilty?; do you find it difficult to concentrate?; do you think about death or suicide?, etc.

And if the person answers yes to at least five of these questions, then voila, by the great miracle of psychiatric transformation, the hapless individual now has another serious problem: a life-threatening brain illness called major depressive disorder, which requires the ingestion of dangerous chemicals for life. What an unmitigated travesty!

And what a contrast to the simple, respectful, insightful, and entirely meaningful approach set out by Mark Bertram and Sarah McDonald in this paper.

“The wide range of current standardised approaches and pathology-laden practices in the mental health field need to be reviewed in the light of: the extent to which they invalidate or validate service users lived experiences.”

FINALLY

I cannot, in this short post, do justice to this paper. Besides its obvious merits, it offers a profound contrast to the drug-pushing, people-shriveling practices of psychiatry. Although the paper does not particularly promote anti-psychiatry, it does demonstrate that even people who have been drawn deeply into the disempowering maw of “mental health”, can still articulate their needs, and can still find fulfillment in productive activity and self-direction.

Mark Bertram and Sarah McDonald have demonstrated that when people are weighed down by life’s adversities, what they need is authentic, validating support, not facile pathologizing checklists, and not tranquilizing or stimulant drugs.

I strongly encourage readers to study this paper and pass it along.