On July 25, 2017, Fredrik Hieronymus et al published a meta-analysis in Molecular Psychiatry. The study is titled Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the absence of side effects: a mega-analysis of citalopram and paroxetine in adult depression. Elias Eriksson, PhD, Head of the Department of Pharmacology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, is the principal author, but as Fredrik Hieronymus is the first author listed, I will refer to the article as Hieronymus et al.

Here’s the abstract:

“It has been suggested that the superiority of antidepressants over placebo in controlled trials is merely a consequence of side effects enhancing the expectation of improvement by making the patient realize that he/she is not on placebo. We explored this hypothesis in a patient-level post hoc-analysis including all industry-sponsored, Food and Drug Administration-registered placebo-controlled trials of citalopram or paroxetine in adult major depression that used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and included a week 6 symptom assessment (n = 15). The primary analyses, which compared completers on active treatment without early adverse events to completers on placebo (with or without adverse events) with respect to reduction in the HDRS depressed mood item showed larger symptom reduction in patients given active treatment, the effect sizes being 0.48 for citalopram and 0.33 for paroxetine. In actively treated subjects reporting early adverse events, who also outperformed those given placebo, the severity of the adverse events did not predict response. Several sensitivity analyses, for example, including (i) those using change of the sum of all HDRS-17 items as effect parameter, (ii) those excluding all subjects with adverse events (that is, also those on placebo) and (iii) those based on the intention-to-treat population, were all in line with the primary analyses. The finding that both paroxetine and citalopram are clearly superior to placebo also when not producing adverse events, as well as the lack of association between adverse event severity and response, argue against the theory that antidepressants outperform placebo solely or largely because of their side effects.”

The fact that antidepressants are only very marginally better than placebos is well-established. In addition, many authors have asserted that even this marginal superiority is an artifact. The reasoning goes like this. In order to prove that a drug is effective, the manufacturer has to prove, not only that it seems to help some people, but that on average it does better than a placebo. This is because placebos do seem to have a beneficial effect, especially in psychiatry. The placebo probably produces its effect by providing attention, raising hopes, etc.

So the manufacturer has to show that the pills (in this case, antidepressants) outperform a placebo. This is done by enrolling a large number of study participants, dividing them at random into two approximately equal groups, giving a placebo to one group, giving the active drug to the other group, and monitoring the outcome.

But – and this is critical – neither the participants, nor the evaluators who are rating them for change – can know who has been given the drug and who has been given the placebo. Any such inkling would undermine the entire procedure.

Studies of this sort are called randomized, double-blind trials, and great pains are taken to ensure that participants and raters remain “blind”.

And here’s the problem: people who have been randomly assigned to take the active drug often come to realize this, because the drug has more detectable effects than a few grams of sugar, or whatever substance is used in the placebo. And this has led many critics of psychiatry to suggest that the even slight superiority of antidepressants is a function of an enhanced placebo effect, rather than any specifically antidepressant property of the drugs themselves.

So here come Hieronymus et al with an interesting proposal: if the slight superiority of antidepressants is due solely to the fact that the side effects have broken the blind, then those participants who are taking the drug and not experiencing side effects should show no improvement beyond that in the placebo group.

THE STUDY

The authors examined all FDA registered double-blind trials of citalopram (Celexa) and paroxetine (Paxil) for “adult major depression” that used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) to assess outcome and included an assessment at week 6. They found 15 such trials (13 for paroxetine and 2 for citalopram).

They combined the results of these 15 studies, and found that trial completers who were taking the drug and who reported no early adverse events did significantly better than completers who took the placebo. HDRS Item 1 (depressed mood) was used to assess outcome. The effect sizes were 0.49 for citalopram (a medium effect) and 0.33 for paroxetine (a small to medium effect).

The authors ran the data several ways, e.g.:

- including adverse effects during the lead-in period;

- including adverse effects during week 1 only, weeks 1 and 2 only, and weeks 1-6;

- using HDRS-17 total score, rather than just the single item depressed mood;

- etc.

The results for the various runs were largely similar, though the result with the HDRS total score was smaller: 0.38 for citalopram and 0.29 for paroxetine.

Under the heading DISCUSSION, the authors state:

“The major finding of this study is that patients treated with either paroxetine or citalopram report a larger reduction in depressed mood than those given placebo regardless of if they report adverse events or not. As such an outcome is not compatible with the theory that the beneficial effect of antidepressants is largely or solely the result of these drugs enhancing the expectation of improvement by causing side effects, our results indirectly support the notion that the two drugs under study do display genuine antidepressant effects caused by their pharmacodynamic properties.”

Note the fairly modest claim embodied in the words “indirectly support”.

and

“Two limitations of this study should be addressed. First, as it only includes data from studies regarding paroxetine or citalopram, it does not allow any conclusions regarding the possible influence of side effects on the response to other antidepressants. The observation that, for these two drugs, a clear-cut difference between groups was observed also in patients not reporting adverse events should however be sufficient to falsify the theory that all drugs regarded as antidepressants exert their action merely by means of their side effects. Second, the possibility that subtle adverse events that are recognized by the patient, but not of sufficient severity to be recorded, could influence the expectation of improvement, should not be excluded. However, the relatively low percentage of patients not reporting any early adverse events in most trials argues against side effects being under-reported.”

Actually, the percentage of participants not reporting any early adverse events was quite substantial; 23% for paroxetine and 21% for citalopram. If even half of these individuals had broken the blind through the detection of subtle unreported effects, this could significantly impact the results.

and

“In summary, although this study does not allow any firm conclusions with respect to the possible existence of a modest association between early side effects and antidepressant response for SSRIs, the results for paroxetine and citalopram being divergent in this regard, it casts serious doubt on the assumption that the superiority of antidepressants over placebo is entirely or largely due to side effects enhancing the placebo effect of the active compound by breaking the blind. We conclude that the placebo-breaking-the-blind theory has come to influence the current view on the efficacy of antidepressants to a greater extent than can be justified by available data.”

Again, note the modest claim “…casts serious doubt on…” But does it even do that? Let’s take a closer look.

DATA ACQUISTION

A meta-analysis is a study that combines the findings of several earlier studies. Because of the combined size, the findings of the meta-analysis are, other things being equal, more robust and reliable than any of the individual studies. Care has to be taken, however, to ensure that the individual studies address the issue or issues concerned, contain the data identified as pertinent, and meet certain standards of quality.

There’s something of a science to this, and almost all modern meta-analyses devote considerable attention to conducting and documenting their search protocols. In addition, almost all take the additional step of listing every individual study in the meta-analysis, so that an interested reader can pull up the originals, and examine each study’s pertinence and quality.

But Hieronymus et al didn’t do this. Here’s their account:

“We requested patient-level data regarding item-wise symptom ratings and timing of adverse events for all industry-sponsored, Food and Drug Administration-registered, placebo-controlled trials regarding adult major depression that have been conducted for fluoxetine (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA), sertraline (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), paroxetine (GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Brentford, UK) and citalopram (Lundbeck, Valby, Denmark). Lilly could not provide us with the requested information regarding fluoxetine, as these data are not available in electronic format, and Pfizer could not provide us with data regarding the timing of adverse events for the sertraline trials. GSK and Lundbeck could however provide us with the requested information regarding paroxetine and citalopram, respectively. To be eligible for inclusion, the trial should have used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) for symptom rating and include an assessment at week 6. Examination of the Food and Drug Administration Approval Packages for the two drugs12–14 confirmed that we had access to all pertinent studies regarding these two drugs with the exception of two small trials, which, according to the Food and Drug Administration approval packages, were prematurely terminated: GSK/07,12 which randomized 13 patients on paroxetine (8 completers) and 12 patients on placebo (7 completers), and LB/87A,13 which randomized 17 patients on citalopram (5 completers) and 17 patients on placebo (4 completers). In addition to the Food and Drug Administration-registered trials, GSK also provided data from four post-registration trials regarding paroxetine.”

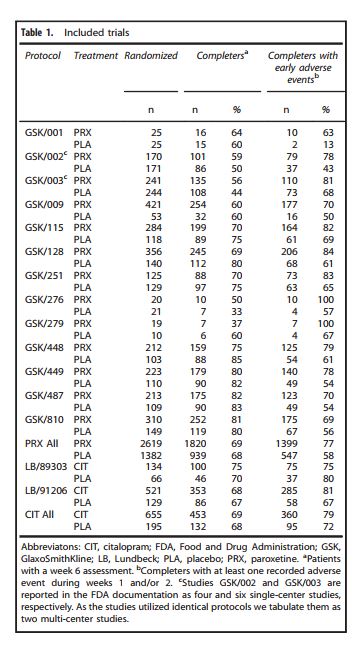

The authors report that they found 13 trials of paroxetine and two trials of citalopram that met their criteria. They listed these on Table 1, reproduced below.

Note that the trials are identified only by GSK and Lundbeck code numbers, and from this it is not possible to find the actual studies as written up, or to make any assessment as to their quality. The FDA approval packages, identified as references 12-14, were of little help. I tried to find individual studies in the FDA packages by matching the data in the above table with data in the packages, but there remained nine studies on which I could find no matches at all.

To provide some context on this matter, I searched PubMedCentral for articles with the words meta-analysis and depression in the title for the three month period June 1 2017 to August 31, 2017. I found seven articles. Six were studies, the seventh was a study proposal. All six of the actual meta-analyses listed all the studies involved. You can find the studies here, here, here, here, here, and here.

So, the question arises: why did Hieronymus et al not provide sufficient referencing for their studies to enable them to be identified and examined? The absence of this level of transparency, which has become standard in medical research, has to be seen as a major weakness.

The authors report that they were unable to include fluoxetine (Prozac) or sertraline (Zoloft) in their meta-analysis because Eli Lilly and Pfizer respectively were unable to provide the necessary data. However, a search in PubMed for studies with fluoxetine and placebo in the title yielded 204 hits; a similar search for sertraline and placebo yielded 108 hits. Surely, from these studies, Hieronymus et al could have found a sufficient number that met their inclusion criteria. Why would they confine their search to only those studies that the manufacturers could provide, when there is no shortage of studies in peer-reviewed journals? Hieronymus et al provide no explanation for this.

THE OUTCOME MEASURE

As mentioned earlier, one of the inclusion criteria for the Hieronymus et al meta-analysis was that the original study had used HDRS-17 scores to assess for improvement in the placebo and drug groups. The HDRS-17 is a clinician-administered scale based on an interview with the participant. It contains the following 17 items: depression; feelings of guilt; suicide; insomnia (early in the night); insomnia (middle of night); insomnia (early hours); work and activities; retardation; agitation; anxiety (psychic); anxiety (somatic); somatic (gastro-intestinal); somatic (general); genital symptoms; hypochondriasis; weight loss; insight. Most of the items are scored 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4. Some are scored 0, 1, or 2; others 0, 1, 2, or 3. Total score is the sum of the item scores. Highest possible score is 53. Generally a score of 0-7 is considered normal. The HDRS-17 is widely used in research, and a score of 20 or higher is usually required for participation in a clinical trial.

It is frequently argued that human emotions are too complex, subtle, and individualized to admit of this kind of numeric measurement, but that would be too wide a tangent in the present context, and so for the sake of discussion, let’s go along with the notion that the HDRS-17 measures depression. But it’s a little more subtle than that. Even a brief review of the wording of the various items reveals that the HDRS-17 was designed to measure, not those ordinary bouts of depression that we all experience from time to time, but rather “depression-the-psychiatric-illness”, specifically “major depressive disorder”. Remember, for decades it’s been a central pillar of psychiatric dogma that the despondency of “major depressive disorder” is emphatically not the ordinary bouts of the blues, but is an illness, identified by the presence of five or more “symptoms” from the DSM’s checklist of nine.

And when we examine the wording of the HDRS-17 items, we find that these so-called symptoms are reflected clearly in the HDRS-17. In that scale, we find items covering depressed mood, diminished interest in activities/work, retardation in speech and movement, agitation, etc. And when we examine the DSM’s nine-item checklist, we find that eight of these so-called symptoms are clearly reflected in the HDRS-17. So researchers who are examining the efficacy of drugs for the amelioration of “major depressive disorder”, typically use the HDRS-17 Total score as their outcome measure. But Hieronymus et al use just one item from the scale: the item that assesses only depressed mood.

And – here’s the kicker – they already knew that this one item overstates the efficacy of SSRI’s. A year earlier (April 2016), three of the four authors and one other author published a paper on the efficacy of SSRI’s. In that study, which was also a meta-analysis, they calculated the effect sizes of the drug vs. placebo for each item on the HDRS-17. They found that Item 1, depressed mood, had an effect size of 0.40 (small to medium). The other 16 items had effect sizes ranging from 0.26 down to negative 0.06 (small to zero). But instead of recognizing that the drugs weren’t very effective in this regard, they cherry-picked the one scale item that exaggerated the drugs’ effects: Item 1.

In the present meta-analysis, they state:

“…only one item from the HDRS-17, depressed mood [Item 1], which was recently shown to be a more sensitive measure for detecting differences between active drug and placebo,17,18 was used as primary measure of efficacy.”

So, is Item 1 by itself a more sensitive measure, or an inflating measure of amelioration of “major depressive disorder”?

In defense of Hieronymus et al, it could be argued that they are simply presenting the drugs in the best possible light. But on the other hand, if as pharma-psychiatry claims, major depressive disorder is a valid illness with known symptoms, and as pharma-psychiatry also claims, antidepressants ameliorate this illness by making appropriate corrections to brain chemistry, shouldn’t the drugs impact all or at least most of the symptoms? Isn’t that what happens when an illness is ameliorated?: the symptoms go away. So whatever Hieronymus et al are measuring by focusing only on Item 1, it is not the composite, polythetic construction that psychiatrists call major depressive disorder.

Perhaps SSRI’s are nothing more than minimally active “happy pills” that induce a slight and temporary relief in mood in some individuals, but have no essentially salutary effects in other areas of life or in the long-term? After all, cocaine is an SRI – serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Like SSRIs – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor – , it also produces a temporary mood change in some individuals, the magnitude of which, incidentally, decreases with prolonged use. But I don’t think anyone claims that it is an effective “treatment” for depression, or for anything else.

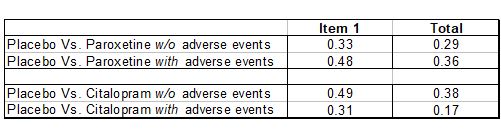

Hieronymus et al did calculate the effect sizes for the HDRS-17 total score. Here’s how they compared with Item 1:

In all four comparisons, using Item 1 instead of the Total Score yields an inflated effect size. Generally, an effect size of 0.2 is considered small, while 0.5 is considered medium. So using Item 1 instead of the Total score inflates the effect size from the low end of the Low to Medium range towards the high end of that range.

OUTCOME: CHANGE FROM BASELINE OR FINAL SCORE?

Most antidepressant trials that use the HDRS-17 as a measuring instrument compare the change in score for the drug participants with the change in score for the placebo group. Mean change from baseline for the drug group is compared with mean change from baseline for the placebo group. And throughout the text of their article, Hieronymus et al indicate that this is what they have done.

“Paroxetine-treated patients both with and without early adverse events outperformed those given placebo with respect to reduction in depressed mood…” (P 2)

“…with respect to HDRS-17-sum reduction…” (p 3)

“…with respect to reduction in the HDRS depressed mood…” (p 1)

“…with respect to reduction in HDRS-17-sum…” (p 3)

“The primary analyses as well as most of the sensitivity analyses suggest the ESs [effect sizes] for the reduction in depressed mood in patients not reporting adverse events to be between 0.3 and 0.5, that is, small to moderate.” (p 5)

[Emphasis added in all above]

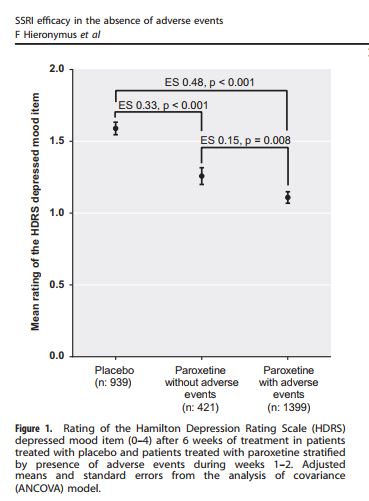

But in the graphic display of their results, Hieronymus et al make no mention of change. For instance, here’s Figure 1.

The vertical axis is labeled “Mean rating of the HDRS depressed mood item”. The “depressed mood item” is Item 1. But note there’s no mention of change or reduction from baseline. So what’s being plotted here is not mean change from baseline, but the mean score on Item 1 at week 6. So the placebo group had a score of about 1.6; the paroxetine group without adverse events, about 1.2, and the paroxetine group with adverse events about 1.1. Low scores are better than high, so both drug groups outperformed the placebo group. But this assumes that the baseline measures for the different groups were equal. Did the authors calculate the change for each individual from baseline to week 6 (by simple subtraction), calculate the group means (by dividing by the number of individuals in each group), and then compare the effect sizes for these means?; or did they just assume baseline equality, calculate the score means for each group at week 6, and calculate the effect sizes on that basis? The two methods could produce very different results. If the authors used the first method, which is the proper way to deal with this data, and is implied by the wording in their text, then why is this not reflected in the graphics they used to display their findings?

Discrepancies of this sort always arouse the concern that the authors ran the data both ways, and presented only the analysis that was more supportive of their pre-existing position. This is particularly the case when insufficient numerical data is provided to enable a reader to check these matters for him/herself.

SUBTLE EFFECTS MIGHT NOT BE REPORTED

The essential point of the article is that people who get the drugs (as opposed to the placebo) are more likely to experience side effects. This would alert them to the fact that they got the drug, and would break the blind. This in turn could engender more hope than the placebo group, and could enhance outcome. The authors found that drug participants who did not report side effects still did better than the placebo group. This, they inferred, argues against the hypothesis.

But the argument collapses if there are subtle drug-revealing effects that are not reported.

The authors recognize this possibility:

“…the possibility that subtle adverse events that are recognized by the patient, but not of sufficient severity to be recorded, could influence the expectation of improvement, should not be excluded.”

“…Should not be excluded.” In other words, the authors are acknowledging that this may be the explanation.

THE SIZE OF THE OUTCOME DIFFERENCES

Although the Hieronymus et al findings are statistically significant, they are very small when considered from a practical, human perspective. (I have discussed the difference between statistical significance and practical significance in an earlier post.)

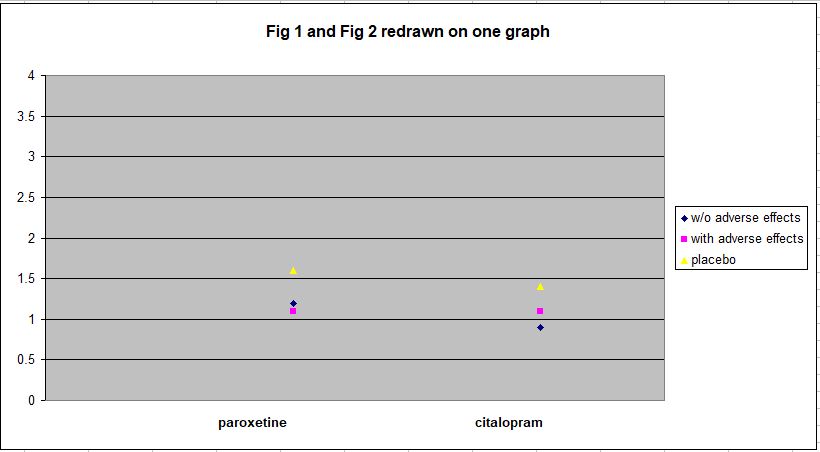

To illustrate the magnitude of the Hieronymus et al findings, here are Figure 1 and Figure 2 from this study redrawn on a single plot.

As can be seen, all the outcomes are within the range 0.9 – 1.6 on HDRS Item 1, which has a range of 0 – 4. To convey some sense of what this means in practical terms, here’s the text of Item 1:

“1. DEPRESSED MOOD (sadness, hopeless, helpless, worthless)

0 |__| Absent.

1 |__| These feeling states indicated only on questioning.

2 |__| These feeling states spontaneously reported verbally.

3 |__| Communicates feeling states non-verbally, i.e. through facial expression, posture, voice and tendency to weep.

4 |__| Patient reports virtually only these feeling states in his/her spontaneous verbal and non-verbal communication.”

The mean rating of both placebo groups at week 6 is around 1.5, i.e. about midway between a score of 1 and a score of 2. And the mean rating for the drug groups is about 1.1. A score of 1 indicates that feelings of sadness, hopelessness, helplessness, and worthlessness are expressed by the individual only in response to questioning. A score of 2 indicates that he or she expresses these feelings spontaneously.

So the drug groups, on average, consist of individuals who express this sadness only when asked, while the placebo groups, also on average, fall about midway between spontaneous expressions of sadness and reporting feelings of sadness when asked. This does not seem like a particularly large difference. And that’s when outcome is assessed using only Item 1, which has been cherry-picked to show an exaggerated effect.

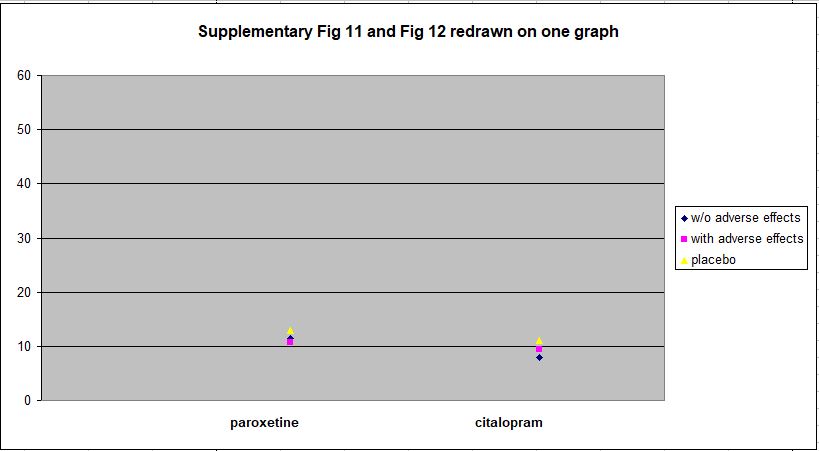

The data for HDRS-17 Total Score, which Hieronymus et al present as Supplementary Figures 11 and 12, show the matter in even clearer perspective. I have redrawn this data on one plot below. The more divergent vertical scale reflects the fact that HDRS-17 Total Score has a range of 0 – 53, while the range for Item 1 is only 0 – 4.

Against the full range of the HDRS-17 spectrum, the differences between the drug and placebo groups at week 6 are clearly trivial.

AUTHORS OWN CONCLUSIONS

As mentioned earlier, the authors’ conclusions were fairly modest and restrained:

“The finding that both paroxetine and citalopram are clearly superior to placebo also when not producing adverse events, as well as the lack of association between adverse event severity and response, argue against the theory that antidepressants outperform placebo solely or largely because of their side effects.” [Emphasis added]

Note the phrase “…argue against…”, as opposed, say, to “refute” or something similar.

and

“We conclude that that the placebo-breaking-the-blind theory has come to influence the current view on the efficacy of antidepressants to a greater extent than can be justified by available data.” [Emphasis added]

Again, this sounds quite a bit short of refutation.

Nevertheless, in a Medscape.com article on August 29, 2017, Elias Eriksson, PhD, the principal author of the study, was quoted as saying:

“‘I think, once and for all, we’ve answered the SSRI question. And we have effectively rebutted the side-effects theory'” [Emphases added]

and

“‘…SSRIs work. They may not work for every patient, but they work for most patients. And it’s a pity if their use is discouraged because of newspaper reports'” [Emphasis added]

In addition, a press release from Gothenburg University dated August 18, 2017 stated:

“The researchers conclude that this study, as well as other recent reports from the same group, provides strong support for the assumption that SSRIs exert a specific antidepressant effect. They suggest that the frequent questioning of these drugs in media is unjustified and may make depressed patients refrain from effective treatment.” [Emphasis added]

Similar copy appeared in ScienceDaily, PsychCentral, MedicalXpress, and other sites.

So there’s a significant discrepancy between the authors’ published conclusions and the message delivered to, and passed on by, the media. The discrepancy is probably a reflection of the fact that it’s relatively easy to get unjustifiably extreme assertions past the media, but not so easy to get them past peer reviewers.

THE FDA, AND PARTICIPANTS’ SELF-RATING SCALES

As I mentioned earlier, I had considerable difficulty matching the studies in Hieronymus et al’s Table 1 and those in the FDA Approval Packages (reference 12; reference 13; reference14) . This wasn’t from any lack of effort or enthusiasm on my part. I combed each page diligently for clues, and did find some matches, but had to give up on others.

However, in one of the packages, identified by Hieronymus as reference 13, I did find a statistician’s summary which contained the following incidental, but extremely interesting, paragraph:

“For all 11 studies, the patient-rated scales showed no efficacy or minimal efficacy. According to the medical reviewer and references provided by the sponsor, these scales have been shown to provide unreliable estimates of symptoms of depression, therefore there is little reason to be concerned about the lack of efficacy.”

So, in the eleven studies in question, the patient-rated scales showed no efficacy or minimal efficacy. Essentially this means that when the participants were asked to rate their own post-trial levels of depression, there were no significant differences between those that took the SSRI and those that took the placebo. And the FDA dismissed this as a matter of no concern, on the basis of information provided by the medical reviewer and references provided by the sponsor. The medical reviewer presumably was an FDA psychiatrist, and the sponsor, of course, was the drug’s manufacturer. The date on this document is September 1992.

I would have thought that as sadness is such an inherently personal thing, the individual’s self-reports would carry a lot of weight. But, of course, if they were showing no efficacy for the SSRI’s, I suppose they had to be dismissed. It has often been suggested that the FDA has had an overly-close relationship with the pharmaceutical companies that they are supposed to be regulating.

I wonder if self-rating scales are still ignored by the FDA today – or do trial designers even use them? Hieronymus et al made no reference to self-rating scales in the study under discussion.

THE BOTTOM LINE

This debate about the efficacy of SSRI’s has been going on for a long time and, at least in my view, the results are fairly clear: the drugs on average have little or no overall positive impact, but probably do induce small emotional changes in certain individuals. Some of the people so affected find the changes pleasant (or at least better than what they had previously); others find them unpleasant. The latter generally stop taking the drugs, though they are usually pressured considerably not to. The former group continue taking the pills, and encounter two apparently contradictory effects: they become physically dependent on the drugs, and the initial pleasant effect wears off. So they go on taking them to ward off withdrawals, which are sometimes interpreted by psychiatrists as “relepase”, and are exposed to the cumulative impact of a wide array of adverse effects.

The study that urgently needs to be done, by truly independent researchers, is a definitive examination of the role that SSRI’s are playing in the mass murders/suicides that have become a regular feature of American life. In this context, half-baked, and obviously biased, regurgitations of old data attempting to prove the efficacy of these drugs is the modern equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns. And incidentally, on this topic the proposal for the Hieronymus et al study, which was published a year earlier, stated that the meta-analysis “…will also be analyzing the possible suicide provoking effect of these drugs.” In fact, there is no mention of suicide in the meta-analysis. Was this an oversight? Or did Hieronymus et al find such a link and choose to suppress it?

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The article lists the following conflicts of interest:

“F[redrik] H[ieronymus] has received speaker’s fees from Servier. E[lias] E[riksson] has previously been on advisory boards and/or received speaker’s honoraria and/or research grants from Eli Lilly, Servier, GSK and H Lundbeck. S[taffan] N[ilsson] and A[lexander] L[isinski] declare no potential conflict of interests.”

In addition, Dr. Eriksson’s CV contains the following:

“Was a member of expert panels/advisory boards for several international pharmaceutical companies: Eli Lilly (USA), Ciba-Geigy (Switzerland), Pfizer (USA), SmithKline Beecham (England), Organon (The Netherlands), Lundbeck (Denmark), Glaxo SmithKline (UK), Rhone-Poulenc Rorer (France) and Schering (Germany). Scientific collaboration with Ciba-Geigy, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Glaxo SmithKline, Merck, and Lundbeck.”

The CV also indicates that Dr. Eriksson has received research funding from Lundbeck and Bristol Myers Squibb.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am grateful to Janne Larsson, a Swedish investigative journalist, for drawing my attention to this study. Janne has also written an article on this matter: Big Pharma strikes back – The Ultimate Antidepressant Study, which I strongly recommend. Interestingly, this article was written in August 2016, more than a year ago, and was based on Dr. Eriksson’s proposal for the meta-analysis. Janne’s article is almost prophetic in its anticipation of the reach and content of Dr. Eriksson’s meta-analysis.